Return to The Temple of Serapis

"Revered Hypatia, ornament of learning, stainless star of wise teaching, when I see thee and thy discourse I worship thee, looking on the starry house of the Virgin [Virgo]; for thy business is in heaven."

Palladas, Greek Anthology (XI.400)

Of the little that is known about Hypatia, the following account by Socrates Scholasticus, which was written sometime in the decade before the death of Theodosius II in AD 450, is the best and most substantial.

"There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more. Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace, that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some of them therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal, whose ringleader was a reader named Peter, waylaid her returning home, and dragging her from her carriage, they took her to the church called Caesareum, where they completely stripped her, and then murdered her with tiles. After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs to a place called Cinaron, and there burnt them. This affair brought not the least opprobrium, not only upon Cyril, but also upon the whole Alexandrian church. And surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort. This happened in the month of March during Lent, in the fourth year of Cyril's episcopate, under the tenth consulate of Honorius, and the sixth of Theodosius [AD 415]."

Ecclesiastical History (VII.15)

In AD 412, Cyril, the nephew of Theophilus, succeeded him as patriarch of Alexandria, the populace of which, says Socrates, "is more delighted with tumult than any other people: and if at any time it should find a pretext, breaks forth into the most intolerable excesses; for it never ceases from its turbulence without bloodshed" (VII.13). Orestes, the new imperial prefect of Egypt, had arrived shortly before and both men became embroiled in a struggle for political power as Orestes resisted ecclesiastical encroachment upon his civil jurisdiction. There had been riots between Christians and Jews and, after a brawl in the theater, the prefect had one of the patriarch's followers arrested and tortured. When Christians were killed in a subsequent attack, Cyril led a mob against the synagogues. The Jews were expelled from Alexandria and their possessions looted. The prefect objected to this forced expulsion and, having rebuffed any attempt at reconciliation, was himself assaulted by monks "of a very fiery disposition" who had come into the city in support of the patriarch. An assailant was captured and tortured to death, and, although Cyril treated the death as a martyrdom, he was obliged to let the matter rest.

A different perspective of Hypatia's death is conveyed by John, Bishop of Nikiu, whose account complements that of Socrates. He blames Hypatia for the prefect's recalcitrance and believed the rumors about her.

"And in those days there appeared in Alexandria a female philosopher, a pagan named Hypatia, and she was devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled many people through Satanic wiles. And the governor of the city [Orestes] honoured her exceedingly; for she had beguiled him through her magic. And he ceased attending church as had been his custom....And he not only did this, but he drew many believers to her, and he himself received the unbelievers at his house....And thereafter a multitude of believers in God arose under the guidance of Peter the magistrate—now this Peter was a perfect believer in all respects in Jesus Christ—and they proceeded to seek for the pagan woman who had beguiled the people of the city and the prefect through her enchantments. And when they learnt the place where she was, they proceeded to her and found her seated on a (lofty) chair; and having made her descend they dragged her along till they brought her to the great church, named Caesarion. Now this was in the days of the fast. And they tare off her clothing and dragged her through the streets of the city till she died. And they carried her to a place named Cinaron, and they burned her body with fire. And all the people surrounded the patriarch Cyril and named him 'the new Theophilus'; for he had destroyed the last remains of idolatry in the city."

The Chronicle (LXXXIV.87-88, 100-103)

It was after these events, relates John, that Hypatia was sought out by the mob, perhaps dragged from the very chair from which she was lecturing, and killed—"torn to pieces" says Philostorgius (Ecclesiastical History, VIII.9) by the Homoousian party (those who accepted the Nicene creed and believed that the Son of God was consubstantial with God the Father). In the Suda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia, "She was torn to pieces by the Alexandrians, and her body was violated and scattered over the whole city. She suffered this because of envy and her exceptional wisdom, especially in regard to astronomy" (Y166).

Hypatia had learned mathematics and astronomy from her father, Theon, described as a member of the Museum at Alexandria (Suda, T205). Indeed, says Philostorgius, she "was so well educated in mathematics by her father, that she far surpassed her teacher, and especially in astronomy, and taught many others the mathematical sciences" (VIII.9). Not satisfied only with mathematics, the Suda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia that preserves the Life of Isidore (a lost account by his pupil Damascius, the last scholarch of the Academy in Athens), relates that she also "embraced the rest of philosophy with diligence. Putting on the philosopher’s cloak although a woman and advancing through the middle of the city, she explained publicly to those who wished to hear either Plato or Aristotle or any other of the philosophers." (In this account, Hypatia, "beautiful and shapely," is the wife of the philosopher Isidore of Alexandria, which is an anachronism, given that he was not born until long after Hypatia's death.)

She is thought to have assisted Theon on both the Almagest of Ptolemy and the Elements of Euclid, which became the standard edition of that text, and to have written commentaries, herself, on the Arithmetica of Diophantus and the Conics of Apollonius, as well as The Astronomical Canon (possibly a revision of her father's commentary on Book III of the Almagest). Editing works on geometry, algebra, and astronomy, the abstract nature of numbers and their properties no doubt appealed to her as a neoplatonist. One can understand that such a woman would have occasion to meet with the magistrates of the city, and that such familiarity would be offensive to her enemies.

Her most adoring pupil was Synesius of Cyrene, a bishop consecrated by Theophilus himself. He addresses seven letters (one a fragment) to Hypatia and refers to her in several more. He laments not hearing from her (Ep.10), accounting her "as the only good thing that remains inviolate, along with virtue. You always have power, and long may you have it and make a good use of that power" (Ep.81). Indeed, about the time of his death (a year or two before her own), he dictated a letter to her as "mother, sister, teacher, and withal benefactress, and whatsoever is honoured in name and deed" (Ep.16). She is the one "who legitimately presides over the mysteries of philosophy" (Ep.137) and "my most revered teacher," who had contributed to the design of a silver astrolabe that Synesius was to present as a gift (Letter to Paeonius). He also requested from her a brass hydroscope (hydrometer) to measure the specific gravity of liquids, describing the device to her in detail (Ep.15). A philosopher, which is how Synesius repeatedly addresses her, Hypatia may have studied with Antoninus, who had prophesied the destruction of the Serapeum.

The Suda (Y166) says that some blamed Cyril for the death of Hypatia, others "the inveterate insolence and rebelliousness of the Alexandrians." She is described as just, chaste, beautiful—

"both skillful and eloquent in words and prudent and civil in deeds. The rest of the city loved and honored her exceptionally....So then once it happened that Cyril who was bishop of the opposing faction, passing by the house of Hypatia, saw that there was a great pushing and shoving against the doors, 'of men and horses together,' some approaching, some departing, and some standing by. When he asked what crowd this was and what the tumult at the house was, he heard from those who followed that the philosopher Hypatia was now speaking and that it was her house. When he learned this, his soul was bitten with envy, so that he immediately plotted her death, a most unholy of all deaths. For as she came out as usual many close-packed ferocious men, truly despicable, fearing neither the eye of the gods nor the vengeance of men, killed the philosopher, inflicting this very great pollution and shame on their homeland."

Twenty-five years earlier, Theophilus had forbidden pagan cults and destroyed the Serapeum at Alexander. Having only recently taken his uncle's place, Cyril needed his own triumph over paganism. Envious of Hypatia (according to Damascius), he plotted to have her killed. John of Nikiu relates (LXXXIV.101-103) that the philosopher was stripped and dragged through the streets until she died; then her body was burned. "And all the people surrounded the patriarch Cyril and named him 'the new Theophilus'; for he had destroyed the last remains of idolatry in the city."

For Gibbon, however, "the murder of Hypatia has imprinted an indelible stain on the character and religion of Cyril of Alexandria" (Decline and Fall, XLVII). Three decades later, Cyril himself would be dead, unlamented by Theodoret, bishop and author of an ecclesiastical history, whose friend Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople, had been attacked by Cyril for not accepting that Mary truly was theotokos, the mother of God.

"At last and with difficulty the villain has gone. The good and the gentle pass away all too soon; the bad prolong their life for years. The Giver of all good, methinks, removes the former before their time from the troubles of humanity; He frees them like victors from their contests and transports them to the better life, that life which, free from death, sorrow and care, is the prize of them that contend for virtue. They, on the other hand, who love and practise wickedness are allowed a little longer to enjoy this present life, either that sated with evil they may afterwards learn virtue’s lessons, or else even in this life may pay the penalty for the wickedness of their own ways by being tossed to and fro through many years of this life’s sad and wicked waves. This wretch, however, has not been dismissed by the ruler of our souls like other men, that he may possess for longer time the things which seem to be full of joy. Knowing that the fellow’s malice has been daily growing and doing harm to the body of the Church, the Lord has lopped him off like a plague and 'taken away the reproach from Israel.' His survivors are indeed delighted at his departure. The dead, maybe, are sorry. There is some ground of alarm lest they should be so much annoyed at his company as to send him back to us."

(Letters, CLXXX).

Of Hypatia, Socrates Scholasticus relates that the Christian populace of Alexandria "murdered her with tiles [ostrakois]," tearing her body to pieces (Gibbon has her being flayed alive). In the Greek lexicon of Liddell and Scott (1889), this is the primary meaning of ostrakon: "a tile or potsherd." But it also has been translated as "shells," (e.g., Bohn's Ecclesiastical Library) and glossed in the context of Hypatia's death as "oyster shells," although the word can mean the hard shell of any animal—as in Carl Sagan's Cosmos, where the word is understood to be abalone shells.

Discarded shards of terracotta, either broken roofing tiles or pieces of pottery, were used in voting, the name of the candidate scratched on these ostraka, which then were counted to determine whether that person was to be ostracized. So the Athenians "cripple and banish whatever man from time to time may have too much reputation and influence in the city to please them, assuaging thus their envy rather than their fear" (Plutarch, Life of Alcibiades, XIII).

The ostrakon pictured above, which is in the Museum of the Ancient Agora (Athens), bears the name of the Athenian statesman Pericles. It dates from 444-443 BC when, in a confrontation between oligarchs and democrats, there was attempt to ostracize him. Instead, it was his rival Thucydides who was banished for ten years (Life of Pericles, XI, XIV).

The Greek word for "bone" is osteon, from which ostreon ("oyster") and ostrakon (a hard, bone-like shell) both derive. By extension, ostrakon also means a piece of earthenware, tile, or pottery—all of which, including oyster shells, were used to cast a vote in ostracism.

Not long before her death, Cleopatra began construction of the Caesareum to honor either Caesar or Antony. Strabo saw it when he was in Alexandria and Philo described the temple in about AD 38 as "full of offerings, in pictures, and statues; and decorated all around with silver and gold; being a very extensive space, ornamented in the most magnificent and sumptuous manner with porticoes, and libraries" (Embassy to Gaius, XXII.151). Centuries later, the Caesareum was converted by the Christians of Alexandria and rededicated as the city's principal church (cf. John of Nikiu, Chronicle, XLI.9ff). Even before construction had been completed, Easter services were celebrated there in about AD 351. Five years later, the church was pillaged at the instigation of Arians, who "seized upon the seats, the throne, and the table which was of wood, and the curtains of the Church, and whatever else they were able, and carrying them out burnt them before the doors in the great street [Plateia], and cast frankincense upon the flame" (Athanasius, History of the Arians, LVI). In the ongoing conflict with pagans, it again burnt down in AD 366. Rebuilt, it was the scene of Hypatia's death in AD 415 and burned for the final time in AD 912.

Coptic tradition held that Mark the Evangelist was martyred in AD 68, when he was seized in the Serapeum, where a festival of Serapis was being celebrated on the same day as Easter, and dragged through the streets of Alexandria. Writing in the tenth century AD, Sawirus, Bishop of Hermopolis in Upper Egypt, relates the death in the History of the Patriarchs (I.145ff).

"But when those unbelievers learnt that the holy Mark had returned to Alexandria, they were filled with fury on account of the works which the believers in Christ wrought...and they sought for the holy Mark with great fury, but found him not; and they gnashed against him with their teeth in their temples and places of their idols, in wrath, saying: 'Do you not see the wickedness of this sorcerer?' And on the first day of the week, the day of the Easter festival of the Lord Christ, which fell that year on the 29th of Barmudah, [Easter itself was the next day, April 25] when the festival of the idolatrous unbelievers also took place, they sought him with zeal, and found him in the sanctuary. So they rushed forward and seized him, and fastened a rope round his throat, and dragged him along the ground....And they drew the saint along the ground, while he gave thanks to the Lord Christ, and glorified him, saying: 'I render my spirit into thy hands, O my God !' After saying these words, the saint gave up the ghost. Then the ministers of the unclean idols collected much wood in a place called Angelion [by the stairs leading up to the Serapeum, II.467], that they might burn the body of the saint there."

One early reviewer in The Church Quarterly Review (Vol. LXII, 1906) cannot repress his frustration with Sawirus, who says nothing about the destruction of the Serapeum itself. "One would have thought that the details of the fall of Serapis and the old paganism would be found imperishably graven in Coptic history; but here, as so often, events of revolutionary importance are passed in silence, while wearisome squabbles on jots and tittles of orthodoxy or heresy are preserved."

Ironically, ten years after the martyrdom of Hypatia, Theodosius established a so-called university at Constantinople, with chairs for grammarians, orators, philosophers, and teachers of law (Codex Theodosius, XIV.9.3). At Alexandria, excavations at Kom el-Dikka in the center of the ancient city have revealed part of a civic complex with both a public bath and theater, as well as twenty rectangular and semicircular auditoria along the portico that served as lecture halls. They had stone benches along three of the walls and, at other end of the room, an elevated chair situated on a dais, with steps leading up to it. In the center was a stone block which may have been used to support a lectern, from which students could read their prepared texts or deliver a speech. The arrangement recalls a statement by the fourth-century rhetorician Libanius, who speaks of the teacher "established in an imposing chair, like judges are....The pupil must go forward in fear and trembling to give an artistically conducted demonstration, which he has composed and learnt by heart" (Chriae, III.7). The complex was constructed in the late fifth or early sixth century AD—too early to have served as a venue for Hypatia, although it is tempting to imagine that she lectured in a hall much like it.

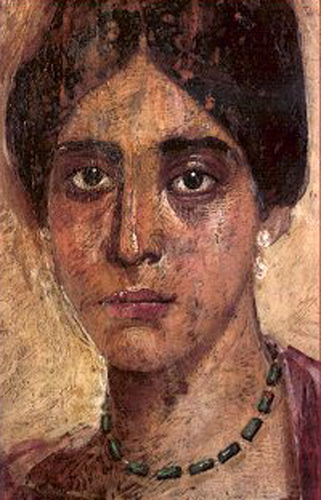

The poignant figure above, her mournful eyes gazing directly at the viewer, is not Hypatia, of course, for whom there is no contemporary representation, but a Greco-Roman "Fayum portrait" from Hawara in Egypt. The elegant but melancholy woman, whose portrait may have been painted because she was sick and dying, wears a necklace of emerald crystals, which complements the purple of her dress, and pearl earrings. The hair styles of imperial Rome were imitated by the fashionable aristocracy in the provinces, especially the women, and provide a means of dating the portrait, which is from the time of Antoninus Pius (AD 138-161), when the use of highlighting was most masterful. In this case, the hair characteristically is parted in the middle and pulled back in a bun worn high on the head. Costume and jewelry, which can be compared to similar pieces with a known chronology, also indicate the date.

References: A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Series II (Vol II: Socrates Scholasticus) (1890) edited by by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace; "The Life of Hypatia from the Suda" translated by Jeremiah Reedy, in Alexander 2: A Journal of Cosmology, Philosophy, Myth, and Culture (1993) edited by David Fideler; The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu (1916) translated by R. H. Charles; The Letters of Synesius of Cyrene (1926) translated by Augustine FitzGerald; Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, Compiled by Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople (1855) translated by Edward Walford; Edward Gibbon: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1995) edited by David Womersley (Penguin Classics); The Greek Anthology (1917) translated by W. R. Paton (Loeb Classical Library); Damascius. The Philosophical History (1999) translated by Polymnia Athanassiadi; Sawirus ibn al-Muqaffa: History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria (St. Mark to Theonas) (1904) translated by Basil Evetts.

"Hypatia and Her Mathematics" (1994) by Michael A. B. Deakin, The American Mathematical Monthly, 101(3), 234-243; "Hypatia of Alexandria" (1940) by A. W. Richeson, National Mathematics Magazine, 15, 74-82; Hypatia of Alexandria (1995) by Maria Dzielska; "Learned Women in the Alexandrian Scholarship and Society of Late Hellenism" by Maria Dzielska, in What Happened to the Ancient Library of Alexandria? (2008) edited by Mostafa El-Abbadi and Omnia Mounir Fathallah; Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius (1993) by Alan Cameron and Jacqueline Long; The Mysterious Fayum Portraits: Faces from Ancient Egypt (1995) by Euphrosyne Doxiadis; Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt (1997) by Susan Walker and Morris Bierbrier; "The Auditoria on Kom el-Dikka: A Glimpse of Late Antique Education in Alexandria" (2010) by Grzegorz Majcherek, Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Congress of Papyrology, American Studies in Papyrology, 471-484; "Scholars and Students in the Roman East" by Samuel N. C. Lieu, in The Library of Alexandria (200) edited by Roy MacLeod (which provides the translation of Libanius); "The Auditoria on Kom-el-Dikka: A Glimpse of Late Antique Education in Alexandria" (2010) by Grzegorz Majcherek, Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Congress of Papyrology, 471-484.

See also The Daughter Library.

![]()