The River Nahe flows below the slopes of the Hunsrück and joins the Rhine at Bingen about nine miles downstream. On the other side of this upland ridge, wending its way through low hills, is the Moselle, its waters immortalized by the Latin poet Ausonius in the Mosella.

"Thy flood moves softly and thy waters limpid-gliding reveal in azure light shapes scattered here and there: how the furrowed sand is rippled by the light current, how the bowed water-grasses quiver in they green bed: down beneath their native streams the tossing plants endure the water's buffeting, pebbles gleam and are hid, and gravel picks out patches of green moss....Yon is a sight that may be freely enjoyed: when the azure river mirrors the shady hill, the waters of the stream seem to bear leaves and the flood to be all o'ergrown with shoots of vines. What hue is on the waters when Hesperus has driven forward the lagging shadows and o'erspreads Moselle with the green of the reflected height! Whole hills float on the shivering ripples: here quivers the far-off tendril of the vine, here in the glassy flood swells the full cluster" (60ff, l89ff).

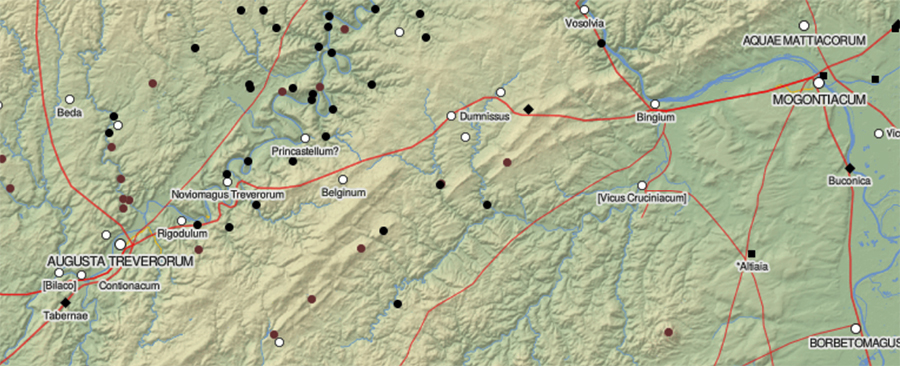

This detail is from the online Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire by Johan Åhlfeldt and hosted by the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. It show the topography of the region and the route taken in AD 368 by Ausonius along the Roman road from Bingium (Bingen) on the Rhine to Augusta Treverorum (Trier) on the Moselle, a distance of some seventy-five miles. (Trier takes its name from the Treveri, a local Celtic tribe—and so Treverorum, "of or among the Treveri.")

"In the first place, he [the general] should have an exact description of the country that is the seat of war, in which the distances between places, the nature of the roads, the shortest routes, by-roads, mountains and rivers, should be correctly provided."

Vegetius, De re militari (III.vi)

This schematic is from the Tabula Peutingeriana, a early thirteenth-century copy of a fourth-century AD itinerarium of Rome's cursus publicus or public way. The route is in stages from Bingium to Dumno (Dumnissus), Belginum, Noviomagnus Treverorum, and Augusta Treverorum, the distance of each marked in Roman miles (curiously, the numbers add up to forty statute miles). Vegetius, writing in the late fourth-century AD, would have approved.

In reading the Mosella, one would think that Ausonius walked to Trier by himself. In fact, he had been ordered to escort Gratian, the eight-year old son of Valentinian I, back to the imperial capital. No doubt, they made the journey by carriage and were accompanied by legionaries.

In Bingen, he "gazed with awe upon the ramparts lately thrown round ancient Vincum [another name for the town]" (2) which had been fortified a decade earlier (in AD 359) by the emperor Julian in preparation for renewed war with the Alemanni (Ammianus Marcellinus, The History, XVIII.2.4). From there, he trekked over the Hunsrück, "a lonely journey through pathless forest, nor did my eyes rest on any trace of human inhabitants" (5) and then to Dumnissus, "sweltering amid its parched fields" (8), Tabernae "watered by its unfailing spring," (8), and Noviomagus Treverorum (Neumagen) "the famed camp of sainted Constantine" (11), which had been occupied by the emperor in defending Gaul against the Franks and Alemanni (AD 306–312). There, Ausonius reached the Moselle, with its "roofs of country-houses, perched high upon the over-hanging river-banks, the hill-sides green with vines, and the pleasant stream of Moselle gliding below with subdued murmuring" (20–22).

Following the river, he finally arrived at Augusta Treverorum (Trier), the regional capital—and its amphitheater. Constantine had captured two of the Frankish chieftains early in the war who, "on exhibiting a magnificent show of games, he exposed to wild beasts" (Eutropius, Abridgment of Roman History, X.3). Panegyrics to Constantine praise the emperor for his victory: "When the fierce kings Ascaricus and his associate [Merogaisus] had been captured you inaugurated your martial endeavors with so much acclaim that we considered it a guarantee of unheard-greatness....so you, Emperor, in the very cradle of your rule, as if you were slaying twin dragons, amused yourself with the celebrated punishments of savage kings" (Panegyrici Latini, IV.16.5–6; also VI.10.1–2 and VII.4.2). In a campaign in AD 308, "Countless numbers were slaughtered, and very many were captured. Whatever herds there were were seized or slaughtered; all the villages were put to the flame; the adults who were captured...were given over to the amphitheater for punishment, and their great numbers wore out the raging beasts" (VI.12.3).

References: Ausonius (Vol. I) (1919) translated by Hugh G. Evelyn White (Loeb Classical Library); In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panegyrici Latini (1994) translated by C. E. V. Nixon and Barbara Saylor Rogers; Roman Trier and the Treveri (1971) by Edith Mary Wightman; Flavius Vegetius Renatus: The Military Institutions of the Romans (1767/1944) translated by Lt. John Clark.