"Suffer me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God. I am the wheat of God, and let me be ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ."

Ignatius, Epistle to the Romans (IV.1)

The martyrdom of Blandina is presented in the Historia Ecclesiastica of Eusebius (V.1), who quotes from a letter written by the Christian communities in Lyon and Vienne, recounting the persecutions that had occurred there in the summer of AD 177. There was a xenophobic prejudice against the Christians of these Gallic towns, many of whom were immigrants from Asia Minor. Prohibited from appearing in public places and increasingly subject to abuse and imprisonment, the Christians of Lyon eventually were arrested.

Interrogated in the forum by the provincial governor, those who professed to being Christians and did not save themselves by renouncing their faith were horribly tortured and condemned to the beasts of the amphitheater, "being made all day long a spectacle to the world in place of the gladiatorial contest in its many forms" (V.1.40). Blandina, a slave girl, was the last to die. Hung from a post, she was exposed to wild animals, but they would not attack. Repeatedly tortured ("the heathen themselves admitted that never yet had they known a woman suffer so much or so long," V.1.56), she eventually was ensnared in a net and trampled beneath the feet of a bull. Her body, and those of others who had been martyred, was left unburied, guarded by soldiers. After six days, the remains were burnt and the ashes cast into the Rhône.

The archetype for all Christian martyrs is Perpetua, a respectable young woman of Carthage, whose Passio is related by Tertullian. Arrested and put in prison, she kept a diary of her ordeal. "A few days later we were lodged in the prison; and I was terrified, as I had never been in such a dark hole. What a difficult time it was! With the crowd the heat was stifling; then there was the extortion of the soldiers; and to crown all, I was tortured with worry for my baby there" (I.2). The night before she was to die in the amphitheater, she had a vision, dreaming that she fought a diabolic Egyptian and defeated him before Christ, her heavenly trainer (lanista), walking victorious through the Porta Sanavivaria (Gate of Life). Martyrs often were idealized as combatants, the spectacle of the arena transposed to the struggle with Satan, imagery which Eusebius, himself, uses in speaking of Blandina: "A small, weak, despised woman, who had put on Christ, the great invincible champion, and in bout after bout had defeated her adversary and through conflict had won the crown of immortality."

Perpetua awoke, knowing that she would triumph the next day. "So much for what I did up until the eve of the contest...about what happened at the contest itself, let him write of it who will" (III.2). Indeed, the events of that day were witnessed and recorded. As an additional humiliation, Perpetua and her maid-servant Felicitas (who herself had given birth just a few days before) were to be dressed as the priestesses of Ceres, which they refused to do. Like Blandina, they then were placed in nets to be trampled to death. In her passion, Perpetua did not even realize her ordeal until she saw that her tunic had been torn and the marks on her body. Later, in the center of the arena, she waited with the others for the thrust of the sword. Pierced in the ribs, the martyr then "took the trembling hand of the young gladiator and guided it to her throat" (VI.3-4).

Perpetua died in March AD 203 as part of the birthday celebration of Geta, the younger son of Septimius Severus. She was twenty-two years old, the same age as Geta when he was murdered by his brother.

"Your blood is the key to Paradise."

Tertullian, De Anima (LV.4-5)

When another martyr, Attalus, was paraded in the arena of Lyon, preceded by a placard declaring him to be a Christian, it was discovered that he was a Roman citizen. Instructions were asked of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, which, in due course, arrived. They essentially were the same as those of Trajan to Pliny the Younger, when he was governor of Bithynia in AD 112 (Letters, X.96-97), complaining about the perverse obstinacy of the Christians: those who persisted in professing their faith were to be punished and those who recanted and worshiped the gods, pardoned. Trajan's other admonition, that Christians were not be sought out, seems to have been ignored (cf. Tertullian, Apology, II, "forbidden to be sought, he was found"). Accordingly, those Christians who were Roman citizens were beheaded and the rest condemned ad bestias, including Attalus.

One is struck by the hatred of the people, who furiously had demanded Attalus by name. Certainly, the contumacious refusal to recant, even under torture, infuriated the populace, as well as the magistrates, who, says Origen, "are greatly distressed at seeing those who bear outrage and torture with patience, but are greatly elated when a Christian gives way under it" (Contra Celsus, VIII.44). To appreciate why, one must remember the stern admonition of Jesus that "whosoever shall deny me before men, him will I also deny before my Father which is in heaven" (Matthew, X.33). Marcus Aurelius, whose Meditations were written about this time, also was perturbed by such unreasonable stubbornness and regarded a readiness to die to come from judgment, "not out of sheer opposition like the Christians, but after reflection and with dignity, and so as to convince others, without histrionic display" (XI.3), a remark that may have been prompted by the events in Lyon.

To honor the pagan gods was to expect their protection and avert the misfortunes, whether famine, disease, or drought, that might result from their neglect. It therefore seemed inexplicable to the inhabitants of Lyon that martyrs would die for their faith, especially since only a worshipful gesture of honor and conformity to tradition was all that was required of them. "'Where is their god? and what did they get for their religion, which they preferred to their own lives?'" (V.1.60). Nor was death, itself, sufficient. The bodies of the Christians were denied burial, so "'that they may have no hope of resurrection—the belief that has led them to bring into this country a new foreign cult and treat torture with contempt, going willingly and cheerfully to their death. Now let's see if they'll rise again, and if their god can help them and save them from our hands'" (V.1.63). Indeed, the very purpose of being sent into the arena to be devoured by beasts or to be burned alive or even to be left on a cross for scavengers was to ensure the complete annihilation of the victim.

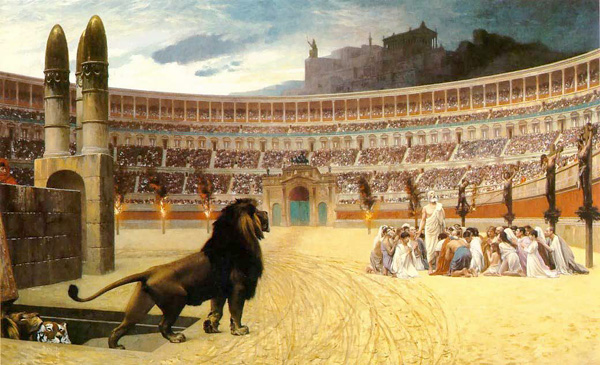

The picture (top) is The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer (1883) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, the figures smeared in pitch and being set afire calling to mind the cruelty of Nero, who set Christians alight in his gardens to serve as human torches. The wrapping, itself, was known as tunica molesta (Juvenal, VIII.235, I.155; Martial, X.25.5; Seneca, Epistles, XIV.5). The other picture, Nero's Torches (1876) is by Henryk Siemiradzki (1843-1902) and in the National Museum (Krakow).

References: Eusebius: The History of the Church (1965) translated by G. A. Williamson; The Acts of the Christian Martyrs (1972) by Herbert Musurillo; Pagans and Christians (1986) by Robin Lane Fox; Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church (1967) by W. H. C. Frend; Pliny: Pliny the Younger: Letters and Panegyricus (1969) translated by Betty Radice (Loeb Classical Library); The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325 (1885-1896) translated and edited by the Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson; The Meditations of the Emperor Marcus Antoninus (1944) translated by A. S. L. Farquharson; A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Series II (1890-1896) edited by by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace; The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (1997) edited by E. A. Livingstone.