"With all their banners bravely spread,

And all their armour flashing high;

Saint George might waken from the dead

To see fair England's standards fly."

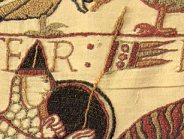

The principal flag of the classical period was the legionary vexillum of Rome, a diminutive of the word velum or "sail" and the origin of vexillology, the study of flags. Hung by its upper edge or top corners from a crossbar supported by a staff or spear, the vexillum later takes the form of the gonfalon (or gonfanon in French heraldry), which was adopted in the Middle Ages by Italian republics and the church for use in ceremonies and processions. In this detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, Count Eustace carries the papal insignia of Alexander II, a gonfanon with three tails charged with a cross, which William of Poitiers says was given to William to signify the church's blessing of his venture.

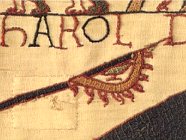

Supposedly the first flag flown in England to be fastened at the hoist, the legendary Raven Flag of the Danish Vikings was thought to portend the outcome of battle. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that such a flag was captured in AD 878 by Alfred. It was carried, too, by Cnut in his victory at Ashingdon in 1016 and may be illustrated here at Hastings. It also is mentioned in the Encomium Emmae Reginae and the Annals of St. Neots, where it is said to have been woven by the daughters of Ragnar Lothbrok, the raven fluttering before victory and drooping before defeat. The English standard was the wyvern, a two-legged winged dragon, shown here lying on the ground in the scene depicting Harold's death. Thought to have derived from the figure of the dragon encountered by Trajan's legions in Dacia, it may be the origin of the red dragon of Wales and the golden dragon of the kings of Wessex, carried, says Henry of Huntington, at the Battle of Burford in AD 752. The dragon's tail is twisted and, like the tails on the fly of the papal banner shown above, demonstrates the same Anglo-Saxon fondness for the curvilinear. Flown vertically with tails at the fly, the pennon frequently appears in the Bayeux Tapestry, where it was carried at the head of a lance. Even though the early devices that decorate these war flags are not thought to be heraldic, they may very well be the prototypes of armorial bearings that were used when heraldry did originate less than a century later. Early in the twelfth century, the first example of arms on a shield is recorded, that of gold lions on azure, given by Henry I to his son-in-law Geoffrey Plantagenet when he knighted him in 1127. Either pointed or swallow-tailed at the fly, the pennon was carried at the head of a lance and, in the Middle Ages, served to identify the knight, who's armorial bearings it displayed, emblazoned so that they appeared correctly in the "at charge" position. Indeed, it is likely that the pennon was the first indication of a knight's cognizance. (A smaller version was the pennoncel.) "On the highest point of the summit he planted his banner, and ordered his other standards to be set up." So the Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, the earliest account of Hastings, relates Harold's preparations for battle. William of Poitiers says that "Harold's famous banner in which the image of an armed warrior was woven in pure gold" was sent to the pope in recognition of the papal banner given to William. Triangular and fringed, it may be depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, lying on the ground in the scene in which Harold's brothers are attacked by mounted knights.

Originally oblong, with a taller hoist than fly, and later nearly square, the medieval banner displayed the personal insignia of kings, nobles, and knights bannerets (those knights who were advanced on the field of battle had the tails of their pennons torn off to form a banner) and was a rallying point in battle. By the mid-fourteenth century, the standard had come to describe the official banner of royalty or nobility. (Whereas insignia are displayed the whole length of the standard, they are limited to the non-tailed area of the gonfanon.) Long, narrow, and tapered (what now would be called a pennant) and ending in a split end, if English, with the cross of St. George at the hoist and then the badge, crest, and motto of its owner (but not the arms), the length was determined by rank. Terminology still varies, however, as can be seen in a line from the twelfth-century Roman de Rou, a chronicle of the Norman conquest by the poet Wace: "The Barons had gonfanons / The Knights had pennons" (XII).