"Hadrian constructed other buildings also for the Athenians...most famous of all, a hundred pillars of Phrygian marble. The walls too are constructed of the same material as the cloisters. And there are rooms there adorned with a gilded roof and with alabaster stone, as well as with statues and paintings. In them are kept books."

Pausanias, Description of Greece (I.18.9)

"Hadrian, when he had constructed many notable buildings in Athens, held games and erected a library of wondrous construction."

Jerome, Chronicle (227th Olympiad [AD 129-132])

Just north of the Roman Agora and separated by a thoroughfare that connected the eastern and western parts of Athens, was another large peristyle court about the same size, the Library of Hadrian, built in AD 132 when the emperor dedicated the Temple of Olympian Zeus. Patterned after Vespasian's Temple of Peace in Rome, the square was enclosed by a thirty-foot high rusticated limestone wall revetted on the interior with marble slabs, the holes for fixing the clamps still visible. Around this enclosing wall were (as Pausanias attests) one hundred columns from Phrygia, thirty along the longer walls and twenty-two on the shorter (counting those on the corners twice). Separated from this peristyle by a screen of two columns, were three exedrae (a central rectangular recess and two semicircular ones) where one could read and talk at leisure, or look out at the ornamental pool and garden that graced the center of the courtyard.

Badly damaged by the Herulians in AD 267, the building was restored by Herculius, praetorian prefect of Illyricum from AD 408-412, who was honored with a statue at the door and an inscription by the philosopher Plutarch (d. AD 432) founder of the Neo-Platonic Academy. Early in the fifth century AD, a building was constructed in the courtyard and, although the quatrefoil plan suggests that it was a church (the Tetraconch, after the design), such an early appearance (c. AD 400) seems unlikely, and it may be that it was a reading room or lecture hall for one of the philosophical schools. If donated by Herculius, this would explain the dedicatory inscription and statue. If a church, it may have been built by Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II.

In AD 435, Theodosius issued an edict requiring that any remaining pagan temples and shrines be destroyed and the sites purified by the erection of a cross (CTh. XVI.10.25). But paganism still seemed to have coexisted with Christianity and, although by the end of the fifth century it is probable that the temples had been deconsecrated, there is no evidence that they were transformed into churches. The Neo-Platonic Academy would not be closed until AD 529, by a decree of Justinian. Deprived of the students who had come to Athens to study philosophy there, the city lost a major source of revenue and its buildings fell into disrepair. Indeed, Procopius complains that Justinian allowed revenue that had been raised for civic needs and public spectacles to be transferred to the treasury, "and consequently in all Greece, and not least in Athens itself, no public building was restored nor could any other needful thing be done" (Anecdota, XXVI.33).

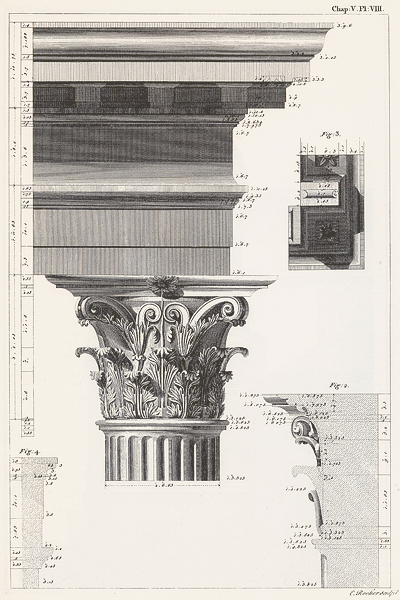

The entrance to the courtyard was through a propylon of four Corinthian columns of veined marble, as can be seen in the restoration above. Across the façade of the principal western wall, which is Pentelic marble, were fourteen Corinthian columns of green cipollino marble from southern Euboea. The seven on the left of the porch still survive and, like those in the Forum of Nerva, are en ressaut, the entablature and attic projecting from the wall and the columns, which stood on a high pedestal, carrying statues. The façade is very similar to the Arch of Hadrian, which has the same free-standing columns on pedestals and is the same date and possibly by the same architect.

Opposite the entrance, along the eastern wall was the library itself, on either side of which were readings rooms and lecture halls. The first course of cabinets that housed the scrolls still are visible; there seem to have been three tiers, which held niches for about sixty book cases.

References: "The Stoa of Hadrian at Athens" (1929) by M. A. Sisson, Papers of the British School at Rome, 11, 50-72; "Honors to a Librarian" by Alison Frantz (1966), Hesperia, 35(4), 377-380; Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens (1971) by John Travlos; The Antiquities of Athens: Measured and Delineated by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, Painters and Architects (1762-1816/2007) introduction by Frank Salmon; "From Paganism to Christianity in the Temples of Athens" (1965) by Alison Frantz, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 19, 185-205.