"Can papyrus grow where there is no marsh? Can reeds flourish where there is no water?"

Job 8:11 (RSV)

"For does a crop grow in any field to equal this [papyrus], on which the thoughts of the wise are preserved? For previously, the sayings of the wise and the ideas of our ancestors were in danger. For how could you quickly record words which the resistant hardness of bark made it almost impossible to set down? No wonder that the heat of the mind suffered pointless delays, and genius was forced to cool as its words were retarded. Hence, antiquity gave the name of liber to the books of the ancients; for even today we call the bark of green wood liber. It was, I admit, unfitting to entrust learned discourse to these unsmoothed tablets, and to imprint the achievements of elegant feeling on bits of sluggish wood. When hands were checked, few men were impelled to write; and no one to whom such a page was offered was induced to say much. But this was appropriate to early times, when it was right for a crude beginning to use such a device, to encourage the ingenuity of posterity. The tempting beauty of paper is amply adorned by compositions where there is no fear that the writing material may be withheld. For it opens a field for the elegant with its white surface; its help is always plentiful; and it is so pliant that it can be rolled together, although it is unfolded to a great length. Its joints are seamless, its parts united; it is the snowy pith of a green plant, a writing surface which takes black ink for its ornament; on it, with letters exalted, the flourishing corn-field of words yields the sweetest of harvests to the mind, as often as it meets the reader's wish. It keeps a faithful witness of human deeds; it speaks of the past, and is the enemy of oblivion. For, even if our memory retains the content, it alters the words; but there discourse is stored in safety, to be heard for ever with consistency."

Cassiodorus, Variae (XI.38)

When, in the first century AD, Pliny wrote about papyrus in Book XIII of his Natural History, it already had been the most common writing material in the ancient world for three millennia. "Our civilization or at all events our records depend very largely on the employment of paper," says Pliny. It is the thing upon which "the immortality of human beings depends" (xxi.68, 70). His description of the plant (xxii.71) is taken from Theophrastus, Aristotle's most famous student, who had written four centuries earlier (Enquiry into Plants, IV.8.4), but Pliny is the only ancient author to relate how papyrus actually was manufactured.

A sedge native to the Delta marshes of Egypt, the thick stems of papyrus reeds (which grew as high as fifteen feet) were cut to size and the green rind peeled away. The fibrous inner pith was split into wide strips and laid lengthwise on a flat, wet surface, first vertically and then horizontally, the edges either touching or overlapping slightly. Pressed or pounded together, the cellulose of the crushed fibers bonded the two layers into a sheet of papyrus or paper (carta) ("paper" itself derives from the Latin papyrus). Dried in the sun, the fluttering sheets sounded at times like thunder (Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, VI.112ff). Although the muddy water of the Nile has no adhesive properties, as Pliny contended (xxiii.77), it did keep the fibers moist and flexible. And the suspended silt may have introduced a fine amount of clay into the process, which would have made them more dense and therefore less absorbent when later written with ink. Aluminum sulfate (alum) in the water also would have contributed to the sizing (absorbency) of the paper and may even have whitened the light-brown sheets.

After any rough spots were polished smooth with ivory or shell and the papyrus sheets trimmed to an appropriate size, they were joined together using a wheat paste of flour and boiling water that had been allowed to set for a day—and to which several drops of vinegar were added to inhibit mold (xxvi.82). Fitted along the grain to form a longer strip, each sheet (scheda, Greek kollema) overlapped the one to the right so that the nib of the pen would not catch where they were glued together. Because this overlap (Greek kollesis), having been flattened with a mallet (xxvi.83), was not much thicker than the pages themselves, it has been conjectured that a vertical strip of papyrus must have been omitted from the right-hand edge where they were joined.

Pliny insists that the resulting roll (scapus) never exceeded more than twenty sheets, about eleven or twelve feet (xxiii.77), which seems to have been the standard manufactured length in the Greco-Roman period—as well as Pharaonic Egypt, where production was a royal monopoly. Although the word usually is translated as "roll," it properly is the rod on which the sheets themselves sometimes were wound. The sentence, in fact, is cited by the Oxford Latin Dictionary to define this particular meaning, which was used by Varro as well in the Menippean Satires (LVIII). The primary definition of scapus, however, is "the stem of a plant, stalk (esp. a long straight one)" and, since Pliny is here talking about the production of papyrus, he may have meant simply that no more than twenty sheets could be made from a single plant.

The height of the sheet, which measured between nine-and-a-half and ten-and-a-half inches, is not specified—likely because it was irrelevant in judging the quality of the papyrus which was esteemed for its fineness, thickness, whiteness, and smoothness (xxiv.78). The finest quality came from the center of the plant and originally was called Hieratica, from the Greek for "sacred," and reserved only for religious texts. So, too, hieratic was the cursive form of hieroglyphs "which the sacred scribes practise" (Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, V.4). Writing from right to left, as the Egyptians did, the scroll presumably would be turned around so the pen didn't snag on the seam. Pliny categorized this first grade as Regia ("royal") or Augusta (after the emperor) and a second, Liviana (after the wife of Augustus), demoting Hieratica to third. (Isidore of Seville says the second grade was called Libyan, after the province, The Etymologies, V.10.) There also were a half-dozen inferior grades, the last of which were made from the increasingly narrow and more fibrous sections of the reed. They either were sold by weight or fit only for wrapping paper. Finally, the tough outer rind served as rope to be used in water (xxiii.76). Plaited together or in cables woven from whole reeds, papyrus rope was renown, Xerxes having ordered its use in the construction of a pontoon bridge across the Hellespont in his invasion of Greece (Herodotus, The Histories, VII.25.1, 36.3).

The width of the sheet was determined by the length to which the horizontal strips could be cut and still remain strong (about eight to twelve inches), wider sheets being superior in that there would be fewer joins to the roll. Sheets of Augusta measuring thirteen digits (about nine-and-a-half inches) were considered best but were so fine as almost to be transparent, which prompted Claudius to have the outer, vertical layer made with stronger fiber, keeping the best grade only for the inner writing surface. He also increased the width of the page to almost twelve inches—on which account Claudian came to be preferred to all other kinds of paper (xxiv.79).

Assembled sheets sometimes were wound around a scapus of wood or ivory, forming a scroll that could be handled by the projecting bosses (cornua or umbilici) on the ends, which could be brightly colored (Martial, Epigrams, III.2, V.6; Tibullus, Elegies, III.1.9). In time, these knobs came to signify the rod itself. This papyrus book roll or volumen (from volvere, "to roll") could be as long as needed but tended to average about thirty feet and seldom more than thirty-five, about the diameter of a wine bottle when wound. Callimachus, the librarian at Alexandria, cautioned against overly long rolls however, remarking proverbially that "a big book is a big evil" (Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, III.72A).

Usually, only one book was written on a scroll (a book of Thucydides, for example, or a Greek play), and there would be the same number of volumes as the books they contained, a physical limitation that tended to define the divisions of literature. Ovid, for example, speaks of the fifteen books of his Metamorphoses as mutatae, ter quinque volumina, formae (I.117). If too long, a book could be divided, as when Pliny the Younger relates that a title written in three volumes later was split into six on account of its length (Epistles, III.5, where he admiringly described his uncle's Natural History as "a comprehensive and learned work, covering as wide a field as Nature herself"). From the time of Augustus, a book of poetry averaged about 700–900 lines, and Martial once fretted that his first book might have to have more repetitions if his own little book (libellus) were to accepted by the public (Epigrams, I.45).

The standard way of reading was to unroll (explicare, "to unfold") the scroll with the right hand, while winding the portion that had been read back up with the left. Someone who is represented holding a scroll in the left hand, therefore, was presumed to have read it, whereas a scroll held in the right signified that it has not yet been perused. Because the papyrus roll had no pages, it was necessary to write in columns (paginae), typically eight-to-ten inches high and containing between twenty-five and forty-five lines, with margins of about half an inch between them and wider margins at the top and bottom. Column width varied but tended to be narrow, averaging about three inches. Iif Homer or another poet were being transcribed, the metrical length of the line tended to determine the width of the column. Although there were no page numbers, columns and lines often were counted. Words seem to have been separated, usually by points (interpuncts), and some marks of punctuation were used, even if arbitrarily. A short stroke (Greek paragraphos) could mark a break in the sense of the text, which was written in capital letters (majuscule). In the middle of the second century AD, in a curious revival of archaism and renewed interest in writers of the early Republic, the Romans adopted the Greek model and wrote without word division or punctuation (scriptura continua), a cultural regression that seems intended to revere literature by making it more inaccessible.

Scrolls were stacked horizontally on a shelf or stored upright in a cylindrical book-box (capsa), which was fitted with a lid and straps for carrying (the scrinium was a larger container). According to Pliny, the only wood suitable for such capsae was beech, which could be thinly-cut (XVI.lxxxiii.229). If particularly valuable, rolls might be wrapped in a protective sleeve and tied with thongs. Martial speaks of some unpublished verses of his being given as a present and "stitched up in a purple cover" (Epigrams, X.93), Tibullus, of a scroll being wrapped in saffron-yellow parchment (Elegies, III.1.9). Often, too, one or two blank sheets of papyrus were attached at the beginning (protocol) and end (colophon) to protect against damage. Author and title might be inscribed, as well as an end-title (subscriptio), which allowed the scroll to be identified even if it had not been rewound.

The earliest description of the scroll is by Catullus, a contemporary of Cicero and Caesar (who once invited him to dinner, Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, LXXIII). He chides another poet for not having to use an erased sheet to compose his rustic verse but writing instead on carta regia smoothed by pumice, its lines ruled with lead in new book rolls with new bosses, and wrapped in red slip-cases and bound with red ties (XXII; Lucian, "purple covers," The Dependent Scholar, XLI). In contrast, Ovid, lamenting his exile from Rome in AD 8, describes his own luckless scroll. "For you no purple slip-case (that's a colour goes ill with grief), no title-line picked out in vermillion, no cedar-oiled backing, no white bosses to set off those black edges: leave luckier books to be dressed with such trimmings: never forget my sad estate" (Tristia, I. 5–10). Later that century (during the reigns of Domitian, Nerva, and Trajan) Martial addresses his libellus, "perfumed with oil of cedar, and, decorated with ornaments at both ends, luxuriate in all the glory of painted bosses; delicate purple may cover you, and your title proudly blaze in scarlet" (Epigrams, III.2).

Curiously, in spite of these literary descriptions, all of which mention the projecting bosses of the scapus about which the scroll was rolled, depictions of the book role itself, whether painted frescoes or marble statues, invariably omit them. An example from Pompeii portrays Terentius Neo and his wife, who proudly declare their literacy. She holds a wax-filled tablet and stylus and he, a scroll. There is no umbilicus and only a red tag (titulus) affixed to the roll identifies its contents.

A pen (calamus) was made from a hard reed that had been trimmed and split; the Egyptians used a softer reed brush (Pliny felt that Egyptian reeds were especially suitable for writing on paper, given their kinship with papyrus, XVI.lxiv.157). Ink (atramentum librarium), which was kept in an inkwell, was comprised of soot from burned pine resin or pitch (lampblack) mixed with a binder of gum arabic (from the thorny acacia tree) and suspended in water (Pliny, XXXV.xxv.41ff; Vitruvius, On Architecture, VII.10.2; Dioscorides, Materia Medica, V.183, where the soot was collected from burning torches and mixed with gum in the ratio of 3:1). To deter the depredations of mice and moths, the back, which usually was left blank, might be stained with cedar oil, imparting a faint yellow color and perfumed scent (cf. Martial, Epigrams, III.2, V.6). Bitter wormwood, too, sometimes was added to the ink to protect the writing from mice (Dioscorides, III.26). In this fresco from Pompeii, one sees a four-leafed tablet (with projections to prevent the wax surfaces from touching when closed), a double inkwell and stylus, and a book roll. What is intriguing, however, is the mysterious object at the left, which has been identified as a scraper or a detailed titulus.

It was possible to rub or wash the writing surface at least partially clean and use the sheet again (palimpsest). Martial wrote to a friend that his latest book (so new that it had not yet been polished with a pumice stone) was being sent along with a sponge so that any offending verses could be wiped clean (Epigrams, IV.10). And when a book of his was drenched in a rainstorm, he ruefully admits that this was how it ought to have been sent (III.100). Both sides of the scroll could be written upon as well (opisthograph). Pliny the Younger was bequeathed 160 such rolls (Epistles, III.5) by his uncle, an economy that Martial disparages (Epigrams, VIII.62).

Eventually, a metallic iron-gall ink was derived from ferrous sulfate (known as copperas or green vitriol) and oak tree galls (boiled to leach out tannic acid) which, because it was not soluble in water, was more suitable for writing. If parchment was reused, the indelible ink had to be scrapped away. Often, these palimpsests are the only form in which a classical work has been preserved, still barely discernible beneath later sermons or saints' lives that had been written over them.

Martial says that a copy of his first book of epigrams, polished with pumice and wrapped in purple, could be bought for five denarii (twenty sestercii) (Epigrams, I.117; or "six or ten sesterces" in a cheaper binding, one "yet unpolished by the pumice-stone, yet unadorned with bosses and cover," I.66). In introducing his thirteenth book, "this papyrus from the Nile" (XIII.1), he declares the slender volume to cost four sesterces (the Latin actually is nummi, signifying "coins") but, if that is too much, it might be had for half that amount—and his bookseller still would make a profit (XIII.3; Horace, too, speaks of his work earning money for the bookseller, The Art of Poetry, 345).

A visitor to Pompeii, which was destroyed in AD 79, when Martial was about forty years old, recorded his expenses for the nine days that he was there. Bread, cheese, wine and oil, leeks and spelt (as well as bread for a slave) averaged about six sesterces a day. For a Roman legionary, whose annual pay late in the first century AD was 300 denarii (Suetonius, Life of Domitian, VII.3), Martial's deluxe volume would have cost almost a week's wages. A common laborer earned slightly more, a denarius per day (cf. Matthew 20:2), and would have had to work almost as long. For Martial himself, who was a member of the equestrian class and therefore had land valued at 400,000 sesterces, his own book would have been quite reasonable. A six-percent return in rents or interest on such property would generate 6,000 denarii a year or almost 66 sesterces a day in income.

Whether papyrus was cheap or expensive, therefore, was determined by the person who could afford it. In the production of book rolls, a standard length of twenty sheets must have been relatively inexpensive, even if the resulting product understandably cost more. For casual correspondence, such as drafts or notes, student lessons, and even legal and official documents, the wooden writing tablet or tabula often was used instead. The leaves of the tablet, which were hinged together with a thong or clasp, had a recessed surface filled with blackened wax that could be inscribed with a bronze or iron stylus, one end of which was flat so the wax could be smoothed and written upon again. Usually the leaves were of silver fir, the light wood revealing itself when the stylus cut through the dark wax. Tablets with two leaves (diptych) were common, although Terentius' wife holds a tablet of three leaves (triptych). The so-called "Sappho" portrait from Pompeii depicts a woman in the same meditative pose holding a tablet of four leaves, and Martial writes of a gift with five (Epigrams, XIV.4). Additional leaves could be threaded together but it was not practical to add too many more.

Although the papyrus roll continued to be used, it was not ideal. The material, itself, was durable. Pliny marvels at having seen documents written on papyrus two-hundred years earlier (xxvi.83) and, when Sulla returned to Rome in 86 BC with the libraries of Aristotle and Theophrastus, the scrolls already were almost 250 years old (Strabo, The Geography, XIII.1.54). The inner horizontal fibers (recto) made it easier for the pen to follow the grain, whereas the outer vertical ones (verso) maintained their strength when the scroll was rolled. But constantly being unrolled and rolled back up again caused abrasion and, even though writing only on one side of the page reduced the problem of wear, it was inefficient. Too, having been read, the scroll then had to be entirely rewound to its beginning, making it that much more cumbersome. Lines and columns were not uniform but varied in length and size; nor were they usually marked, which made citation difficult and often inaccurate.

Parchment (membrana or pergamena) is the treated skins of sheep and goats, which have been soaked in lime and scraped, stretched and dried, and rubbed smooth with pumice. Writing in the fifth century BC, Herodotus says that the Ionians once had called papyrus scrolls "skins" because, at one time "long ago," when it was scarce, the skins of sheep and goats had been used instead (The Histories, V.58.3). Pliny (quoting Varro) is mistaken, therefore, when he says that parchment was invented at Pergamon because of an embargo on the export of papyrus from Alexandria (xxi.70), although a shortage may have forced the library there to convert to the use of parchment, at least temporarily, or to have refined its manufacture.

In an important innovation, the Romans substituted parchment for the wooden leaves of the tabula to form the notebook, which was the prototype of the modern book. Cut into sheets, parchment was folded in half to yield a gathering (or quire) of two leaves or four pages, one-half the width of the original folio. (It is disconcerting to realize that a double folio page represented the hide of a whole animal.) Folding the sheet again gave four leaves or eight pages (quarto); and yet again, eight leaves or sixteen pages (octavo), which was the size of most notebooks. Papyrus also could be used to make books, but the sheets were not large enough to be folded more than once, which meant that a papyrus book had to be formed from a number of single-sheet quires.

Stitched together and protected by a cover, the parchment notebook was used for accounts, notes, drafts, and letters. The earliest evidence for its literary use is Martial, who, writing toward the end of the first century AD, commends his little book (libellus) to an unaccustomed public: "Assign your book-boxes [scrinia] to the great, this copy of me one hand can grasp" (I.2; also parchment, XIV.184, 186, 188, 190, 192). Large books, he boasts, should be confined to scrinia. Because of its resemblance to a block of wood (caudex), the tablet came to be called a codex. There is a similar association in the Latin word for book (liber), which originally meant "bark." So, too, the Greek name for papyrus, biblos (after the Phoenician port from which it was traded), came to mean the scroll made from it, then "book," and ultimately, the Bible.

And yet, the practical advantages of the codex in terms of size and convenience and the better, more durable protection offered by its covers were not, by themselves, sufficient reasons to replace the papyrus scroll. That impetus came from the early Christian church, which adopted the form of the codex to differentiate its writings from the sacred books of Jewish scripture (which were copied only in the format of the scroll) and from pagan literature, which also was equated with the scroll. More importantly, the codex permitted longer texts, such as the Gospels, to be contained within a single volume and to be referred to more easily. Although papyrus continued to be used by official scribes and copying houses and for literary production, as was the wooden tablet for more ephemeral material, by the second century AD a shift from papyrus scroll to parchment codex was evident. By the fourth century AD, Christianity had triumphed, and the codex completely replaced the scroll, just as, in time, parchment replaced papyrus.

It was a development in the history of the book as monumental as the invention of printing a thousand years later.

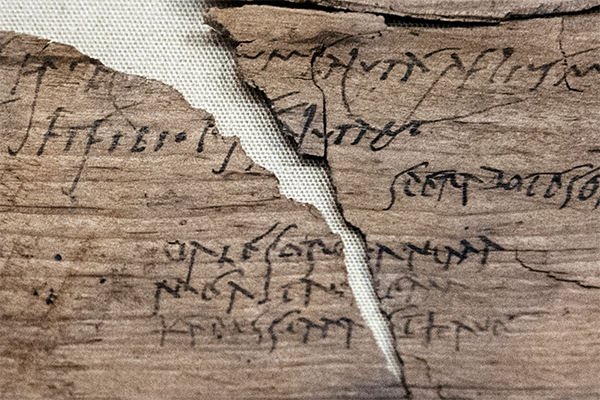

In 1973, the first cache of wooden leaf tablets was discovered at the Roman outpost of Vindolanda (Chesterholm) in northern Britain, near where Hadrian's Wall later would be built. Made of native alder or birch and cut so thin that they could be folded in half (diptych) without splitting, these fine-grained slivers of wood veneer record letters and other ephemera for which a heavier and more expensive stylus-written tablet was impractical. On one such letter, a detail of which is pictured above, there is an invitation to the prefect's wife, inviting her to celebrate the birthday of Claudia Severa. Written in ink by a scribe, the concluding valediction is that of Severa herself: "I shall expect you sister. Farewell, sister my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail." Composed at the turn of the first century AD, it is one of the earliest examples of Latin written by a woman.

Confusingly, these alder leaf tablets are known as tilia, after the lime (or linden) tree, which Theophrastus says sometimes was used in the production of writing-cases (Enquiry into Plants, V.7.5, III.13.1). Pliny comments that, between the bark and the wood of the tree, "there are a number of thin coats, formed by the union of numerous fine membranes; of these they make those bands (ribbon-like wreathes) which are known to us as 'tiliae'" (XVI.xxv.65). He also says that the citrus wood was valued as a veneer, being able to be cut into thin layers (XVI.lxxxiv.231, as was alder).

Martial speaks of citrus wood in the Apophoreta, a series of paired couplets that describe gifts that could be given to guests at the Saturnalia, the first from a rich person, the second from a poorer one. Three of them are a pugillares (from pugillaris, "belonging to the fist or hand") which, like Martial's first book of epigrams, could be held in one hand. A pugillares of citrus wood is contrasted with a less expensive waxen tablet of five leaves, an ivory one with a three-leaf tablet, and another of parchment with a very small Vitellian tablet, which could be used to convey an amatory note to one's mistress (Epigrams, XIV. 3, 5, 7).

An excursus on etymology and orthoepy—from the titulus that identified the content of the scroll comes the English word "title," just as the Greek equivalent for this parchment slip or tag was sillybos (sometimes sittybos) from which, although the etymology is confused, "syllabus" derives for the contents of a course. A titulus ("small inscription") also was known as an index, from indico "to point out," indicating the title of the work (Ovid, Remedies for Love, I.1.7) and often the author's name (Livy, The History of Rome, XXXVIII.56.6). In commending Atticus for his library, Cicero writes "Nothing can be more charming than those bookcases of yours, since the title-slips [sillybis] have shown off the books" (Letters to Atticus, IV.8.2; also IV.5.4, where the word is sittybis). Usually, these slips (which were attached by the owner and not the author of the work) were glued to the edge of the scroll itself or hung from the projecting end of the rod on which the scroll was wound. Certainly they would have made the scrolls, tidily arranged and shelved, more immediately accessible—unless these dangling slips of paper became detached and lost.

Latin c[h]arta (paper) is a transliteration of the Greek, and both carta and charta are proper Latin words and pronounced the same, with a hard "k"—as in "cart" and not "chart." The most well-known example of this difference in spelling is Magna Carta, the Great Charter of rights acceded to by King John in 1215. (It is not preceded by "the" because Latin does not have articles.) The name first appeared in the thirteenth century as magna carta but, by the late nineteenth, charta had become the favored spelling. Even as late as 1965 (on the 750th anniversary of the Charter), the editors of the Journal of the American Bar Association begrudgingly accepted Magna Carta in an article's title when the author insisted that scholars had used the term for decades in their discussion of the document to emphasize the correct pronunciation of the word. Fifty years later on the 800th anniversary, The Huntington Library still felt obliged to explain how its exhibition Magna Carta: Law and Legend 1215–2015 came to be named as it did.

There is some ambiguity in Pliny's account of how papyrus was manufactured, especially in his remark that "Paper is made from the papyrus, by splitting it with a needle [diviso acu] into very thin leaves, due care being taken that they should be as broad as possible. That of the first quality is taken from the centre of the plant, and so in regular succession, according to the order of division" (xxiii.74). It is unclear, for example, whether principatus medio ("center of the plant") means the center of the pith or the middle of the stalk, i.e., a section cut midway between the flowering top and the waterline. Bülow-Jacobsen argued that, since the pith of the papyrus is the same throughout when seen in cross-section, the thicker middle section of the tapering plant must be meant—which was about the width of a man's wrist (Theophrastus, IV.8.4). As to the lowest cubit (about eighteen inches), Herodotus contends that it was roasted and eaten (The Histories, II.92.5).

In trying to reconcile "narrow strips" (philyras) and "as broad as possible" (quam latissimas), Hendriks proposed that, rather than being cut by a knife into successively narrow strips (either along each side of the triangular stem or from top to bottom), the fibers were, as Pliny recounts, carefully peeled apart by a needle in a continuous spiral which, when unrolled, formed a single, wide strip. But it must have been a tedious, exacting process to separate the pith in such a fashion, the soft pulp likely tearing—and made more so by the tapering stem, which did not allow for the fibers to remain parallel to one another along their length. It has been suggested, too, that there may have been a lacuna in the original and that the phrase should read simply diviso ac<c>u<rate>, "carefully divided."

One of the most interesting discussion of books is by the Roman jurist Ulpian, who flourished early in the third century AD, during the reign of Caracalla. His legal opinions survive in extracts from the Digest, a consolidation of Roman law published by the Byzantine emperor Justinian three-hundred years later. Commenting on two other jurists who wrote in the first-century AD, Ulpian sought to define what exactly is meant by "a book," at least when donated in a will. "Under the term books are included all rolls, whether of papyrus or parchment or any other material....But are they due if they are in codex-form, either of parchment or papyrus or ivory or some other material, or of waxed tablets" (XXII.52)? When books have been bequeathed, parchments also are to be included. If one-hundred books have been given, "we shall give him a hundred rolls, not a hundred of what someone has measured out by his own ingenuity to suffice for writing a book. For instance, if he should have the whole of Homer in one roll, we shall not count this as forty-eight books, but shall take the whole roll of Homer to be one book" (52.1). Moreover, "books fully written out, though not yet hammered or ornamented, will be included. So will books not yet glued together or corrected; and even parchments not yet bound together will be included" (52.5). Blank parchment or papyrus obviously are not to be included although, if a scholar were to leave his entire collection of papyri when his library comprised nothing but books, then no doubt books were intended, "because many people commonly call books papyri" (52.4).

A more entertaining read about scrolls is Ode to a Banker, the twelfth in a series of historical novels by Lindsey Davis.

The wall painting, which depicts a pied kingfisher hunting fish in a grove of papyrus, comes from the palace of Akhenaten at El-Amarna on the Nile and dates to about 1350 BC. It now is in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford). The fresco is in the National Archaeological Museum (Naples) and the leaf tablet in the British Museum (London).

References: "Book Production" by Susan A. Stephens, in Civilization of the Ancient Mediterranean (Vol. 1) (1988) edited by Michael Grant and Rachel Kitzinger, pp. 421-436; The Birth of the Codex (1983) by Colin Roberts and T. C. Skeat; Cambridge History of Classical Literature (1982) edited by E. J. Kenney and W. V. Clausen; Books and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome (1951) by Frederic G. Kenyon; Ancient Libraries (1940) by James Westfall Thompson; The Oxford Classical Dictionary (1970) edited by N. G. L. Hammond and H. H. Scullard; Pliny, Natural History (1960) translated by H. Rackham (Loeb Classical Library); Ovid: The Poems of Exile (2005) translated by Peter Green; Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages (1990) by Bernhard Bischoff; Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature (1991) by L. D. Reynolds and N. G. Wilson; Cassiodorus: Variae (1992) translated by S. J. B. Barnish; "Ancient and Medieval Accounts of the 'Invention' of Parchment" (1970) by Richard R. Johnson, California Studies in Classical Antiquity, 3, 115-122; "Pliny, Historia Naturalis XIII,74–82 and the Manufacture of Papyrus" (1980) by Ignace H. M. Hendriks, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 37, 121-136; "Pliny the Elder and Standardized Roll Heights in the Manufacture of Papyrus" (1993) by William A. Johnson, Classical Philology, 88(1), 46-50; "The Length of the Standard Papyrus Roll and the Cost-Advantage of the Codex" (1982) by T. C. Skeat, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 45, 169-175; "Pliny the Elder and the Making of Papyrus Paper" (1995) by Andrew D. Dimarogonas, The Classical Quarterly, 45(2), 588-590; "Manufacture of Black Ink in the Ancient Mediterranean" (2017) by Thomas Christiansen, The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists, 54, 167-195; "The Reconstruction of Papyrus Manufacture: A Preliminary Investigation" (1989) by A. Wallert, Studies in Conservation, 34(1), 1-8; "Papyrus" (2000) by Bridget Leach and John Tait, in Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw, pp. 227-253; Papyrus in Classical Antiquity (1974) by Naphtali Lewis (the classic study); The Digest of Justinian (Vol. 3) (1985) translated by Alan Watson; "Writing Materials in the Ancient World" (2009) by Adam Bülow-Jacobsen, in The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology, edited by Roger S. Bagnall, pp. 3-29; "Principatus Medio. Pliny. N. H. XIII, 72 sqq." (1976) by Adam Bülow-Jacobsen, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 20, 113-116; "Was Papyrus Regarded as "Cheap" or "Expensive" in the Ancient World?" (1995) by T. C. Skeat, Aegyptus, 75(1/2), 75-93; De Materia Medica: Being an Herbal with Many Other Medicinal Materials (2000) translated by Tess Anne Osbaldeston; Notiziario del Portale Numismatico dello Stato Itinerari e Guide [Pompeii N. 12: The World of Money at Pompeii] (2014) by The Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Activities, and Tourism; The Library of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum (2005) by David Sider; "Tab.Vindol.291.Birthday Invitation of Sulpicia Lepidina," Roman Inscriptions of Britain (online); The Herbal of Dioscorides the Greek (2000) translated by Tess Anne Osbaldeston.

See also Library of Alexandria.