Born in Siena, Pier Andrea Mattioli (1501-1577) was personal physician to Ferdinand I and a prolific commentator on De Materia Medica of Dioscorides, the codex of which Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq had attempted to acquire from the court of Süleyman I (the Magnificent). Although he failed to procure the manuscript, he did return from Constantinople, says Mattioli, with the first lilac (from the Arabic lilak) to be seen in Europe.

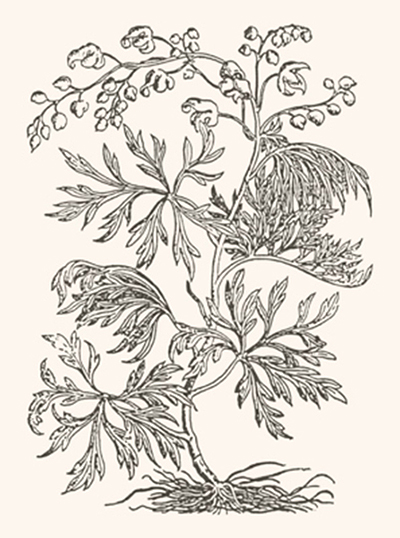

The woodcut above from Mattioli's Commentarii in Sex Libros Pedacii Dioscoridis (1565) is the first printed image of the flower. A tulip also is illustrated, mistakenly identified as a narcissus. Indeed, before the more familiar name was accepted, the tulip (tulipa) often was referred to as lilionarcissus (and is classified among the Liliaceae). Although this woodcut of the lilac has been colored by hand, such illustrations usually were monochromatic.

The Commentarii was published in Italian in 1544, with a lavishly illustrated Latin edition in 1554 that brought Mattioli to the attention of Ferdinand I, then Archduke of Austria, who summoned him to court in Prague the next year to treat his son, Maximilian II. With financial support from the imperial court, there were translations in Czech (1562) and German (1563), until the commentaries virtually displaced the original Greek. Determined to be the undisputed authority on Dioscorides, Mattioli attacked anyone who had the temerity to disagree with him. But he also observed and cataloged many plants, himself, aided by correspondents such as Gesner, Quackelbeen, and Busbecq, who lent him two less famous manuscripts of Dioscorides that he had brought back from Constantinople. This colored woodblock print of the aconite plant is from the 1568 Italian edition of Mattioli's Commentarii.

Nearly six hundred larger, more detailed woodcuts were commissioned for the Bohemian edition which, because they fill the entire area, are thought to have been designed directly on the woodblocks, themselves. They were used again for the German edition, as well as the Latin edition of 1565, the most important of the Commentarii, which illustrates more than nine hundred plants (and one hundred animals).

Many of these woodblocks survive, having been bought in the eighteen-century by a French botanist to illustrate a two-volumes work of his own on trees and shrubs. Kept in the family, a few were sold in the 1950s and then, in the late1980s, one hundred and ten blocks were offered. The illustration of Aconitum napellus (monkshood) is from the catalog of that sale, the flower stem curved to fit the confines of the block. Mattioli had observed the poisoning of two condemned criminals in Rome and, in Prague, tested aconite, himself, on a prisoner who volunteered to take the poison rather than be executed on the public scaffold.

References: Ein Garten Eden (2001) by H. Walter Lack and translated by Martin Walters; The Mattioli Woodcuts (1989) by William Patrick Watson, Sandra Raphael, and Iain Bain; Mattioli's Herbal: A Short Account of Its Illustrations, with a Print from an Original Woodblock (2003) by John Bidwell; "The Letter: Private Text or Public Place? The Mattioli-Gesner Controversy about the aconitum primum" (2004) by Candice Delisle, Gesnerus, 61, 161-176.