Writing in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum ("Ecclesiastical History of the English People"), Bede complains about the obstinacy of the Celtic Church in Britain, especially in regard to the celebration of Easter (Dies Paschae). He relates how Augustine admonished his Celtic brethren.

"Now the Britons did not keep Easter at the correct time, but between the fourteenth and twentieth days of the moon-- a calculation depending on a cycle of eighty-four years. Furthermore, certain other of their customs were at variance with the universal practice of the Church. But despite protracted discussions, neither the prayers, advice, or censures of Augustine and his companions could obtain the compliance of the Britons, who stubbornly preferred their own customs to those in universal use among Christian Churches.... The Britons admitted that his teaching was true and right, but said again that they could not abandon their ancient customs without the consent and approval of their own people... In reply, Augustine is said to have threatened that if they refused to unite with their fellow-Christians, they would be attacked by their enemies the English; and if they refused to preach the Faith of Christ to them, they would eventually be punished by meeting death at their hands. And, as though by divine judgement, all these things happened as Augustine foretold."

One is struck by the hostility of feeling. Bede regards the nonconformity of the Celtic Britons not merely as sinful but heretical. They are called perfidi, a term he reserves for the Pelagian heretics. And, when these same monks, who had been praying for British victory at the fateful Battle of Chester in AD 610, were slaughtered by the heathen Æthelfrith, the destruction is considered just punishment for their recalcitrance.

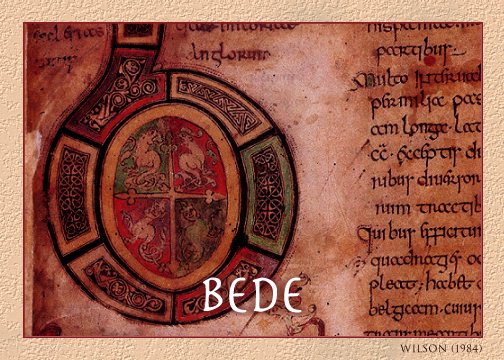

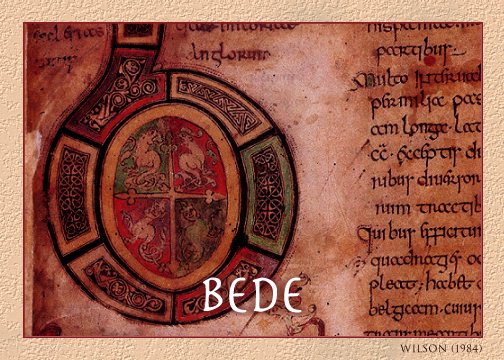

The handsome initial illustrated above is a detail from the opening page of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica, "Britain, once called Albion, is an island of the ocean..." Written in southern England in the second half of the eighth century, with glosses in Old English, the copy is virtually contemporary with its author. Identified as Cotton Tiberius C.ii, it once was in the collection of the antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton. Two other manuscripts are older still: the Moore MS, which once belonged to the bishop of Ely, was written in Northumbria in, or so after, AD 737 (just two years after the death of Bede, himself). The Leningrad MS was copied not later than AD 747 and is very similar to the Moore MS but even more accurate, and both may have derived from Bede's own copy.

This contention between the Celtic and Roman churches as to the proper observance of Easter was a matter that would not be resolved until the Synod of Whitby in AD 664, when King Oswy of Northumbria decided in favor of the Roman church. That the situation was intolerable can be seen in Oswy celebrating Easter according to the Celtic custom, while his wife still was observing Palm Sunday. Bede records the debate.

"About this time there arose a great and recurrent controversy on the observance of Easter, those trained in Kent and Gaul maintaining that the Scottish [Irish] observance was contrary to that of the universal Church.... King Oswy opened by observing that all who served the One God should observe one rule of life, and since they all hoped for one kingdom in heaven, they should not differ in celebrating the sacraments of heaven. The synod now had the task of determining which was the truest tradition, and this should be loyally accepted by all."

Both sides presented their argument, the Romans at times impolitic in the confidence of their position.

"The only people who are stupid enough to disagree with the whole world are these Scots and their obstinate adherents the Picts and Britons, who inhabit only a portion of these two islands in the remote ocean.... But you and your colleagues are most certainly guilty of sin if you reject the decrees of the Apostolic See and the universal Church which are confirmed by these Letters. For although your Fathers were holy men, do you imagine that they, a few men in a corner of a remote island, are to be preferred before the universal Church of Christ throughout the world?"

After asking whether Peter truly had been given the keys of heaven, King Oswy made his decision. "Then, I tell you, Peter is guardian of the gates of heaven, and I shall not contradict him. I shall obey his commands in everything to the best of my knowledge and ability; otherwise, when I come to the gates of heaven, he who holds the keys may not be willing to open them."

In quoting a long letter from Ceolfrid to the king of the Picts, Bede reiterates the Roman church's position on the observation of Easter. It was to be celebrated in the first month of the year, in the third week of that month, and on the first Sunday of that week, that is, the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox on March 21.

"Therefore, whatever moon is at the full before the equinox, when it falls on the fourteenth or fifteenth day, rightly belongs to the last month of the preceding year, and consequently is not suitable for keeping Easter. But the full moon falling either on or after the equinox itself certainly belongs to the first month; on it the ancients used to keep the Passover, and when Sunday comes, we should keep Easter.... Whoever argues, therefore, that the Paschal full moon can occur before the equinox, disagrees with the teaching of the scriptures in the observance of our highest mysteries, and allies himself with those who believe that they can be saved without the assistance of Christ's grace."

The dispute between the Celtic and Roman churches was in determining when the third week of March occurred: whether between the fourteenth and twentieth of the month, as the Celtic church believed, or between the fifteenth and twenty first, as Bede insisted.

Originally, the early Christians had followed the Jewish calendar and celebrated the resurrection on the Passover, which was the fourteenth day of Nisan, the first month of the new year. In time, Easter was separated from the Jewish festival and came to be celebrated on a Sunday. The two dates could coincide, however, and in AD 325 the Council of Nicaea declared that Easter was to be celebrated on the same Sunday. Still, when Easter fell on the fourteen, the Roman church celebrated it the following week, on the twenty-first; the Celtic church, the week before.

There was another problem. Easter is a moveable feast, its date based on a lunar cycle. To correlate the lunar year with the solar year of the Roman calendar, a certain number of days have to be intercalated into a cycle of so many years. Easter was calculated based on these cycles. But, when Rome adopted the more accurate nineteen-year cycle followed by the church at Alexandria, the Celtic church continued to adhere to one based on an eighty-four year cycle.

The new Easter table was compiled by Dionysius Exiguus in AD 525. Rather than use the regnal year of the emperor Diocletian, who had introduced the nineteen-year cycle to Egypt but also had persecuted the Christians, Dionysius reckoned the years from the Incarnation, which he identified as anno Domini. Accepted by the Roman church, this table was used, with revisions, including Bede's own, until the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in the sixteenth century. Bede's Ecclesiastical History, in fact, was the first major historical work to use anno Domini as the basis for its chronology.

The Celtic church insisted on reckoning its own date for Easter and continued to abide by the older cycle, an adherence to custom and tradition that nevertheless challenged the ecclesiastical discipline of Rome. It is this recalcitrance and deviation from orthodoxy that so incensed Bede. Indeed, the church at Iona on Britain's far western shore did not follow the paschal calendar of Rome until AD 716 and the Welsh church not until AD 768, almost forty years after Bede had completed his history of the English church.

(As well as providing the date for Easter, the tables have great historical value. Often, they did not fill the whole page but left a margin in which events were recorded next to the year in which they occurred. This record is known as an Easter annal and provides a basis for dynastic, ecclesiastical, and military history. One of the earliest references to Vortigern, for instance, is an entry to an Easter annal, where there also is mention of the battle at Badon and Arthur.)

The illustration is a detail from the opening page of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica, Tiberius C.ii.