"There was another exhibition that was at once most disgraceful and most shocking, when men and women not only of the equestrian but even of the senatorial order appeared as performers in the orchestra, in the Circus, and in the hunting-theatre [Colosseum], like those who are held in lowest esteem. Some of them played the flute and danced in pantomimes or acted in tragedies and comedies or sang to the lyre; they drove horses, killed wild beasts and fought as gladiators, some willingly and some sore against their will."

Cassio Dio, Roman History (LXI.17.3)

The scandalous events described above, including an elephant walking on a tightrope, were provided by Nero in honor of his mother, whom he had murdered (as well as his first and second wife, as well as his step-sister and step-brother). In recounting the Neronian games, Tacitus, relates, too, that "Many ladies of distinction, however, and senators, disgraced themselves by appearing in the amphitheatre" (Annals, XV.32). Later, in entertaining the king of Armenia, Nero gave a gladiatorial exhibition in which Ethiopians appeared, both men, women, and children (Dio, Roman History, LXIII.3.1). And Petronius, who Nero forced to commit suicide, speaks of a woman who was to fight from a chariot in the manner of essedarii (Satyricon, XLV), probably armed with bow and arrow to compensate for a disadvantage in strength.

Increasingly elaborate displays were hosted by Titus in the dedication of the Colosseum and baths. "There was a battle between cranes and also between four elephants; animals both tame and wild were slain to the number of nine thousand; and women (not those of any prominence, however) took part in despatching them" (Dio, LXVI.25.1). By drawing attention to the fact that these venatores are undistinguished performers, Dio neatly avoids any implied criticism of the emperor as sponsor of the games. Martial, whose Spectacles were written to celebrate the inauguration of the amphitheater in AD 80, also speaks of women in the arena, one clothed as Venus herself, the ancestor of Rome. "It is not enough that warrior Mars serves you in unconquered arms, Caesar. Venus herself serves you too" (VI). Another overcomes a lion, "Illustrious Fame used to sing of the lion laid low in Nemea's spacious vale, Hercules' work. Let ancient testimony be silent, for after your shows, Caesar, we now have seen such things done by women's valor" (VIII).

Domitian, the younger brother of Titus, who succeeded him the following year, is explicitly said to have presented women as gladiators. He "gave hunts of wild beasts, gladiatorial shows at night by the light of torches, and not only combats between men but between women as well" (Suetonius, Life of Domitian, IV.1) and "sometimes he would pit dwarfs and women against each other" (Dio, LXVII.8.4). Statius may be referring to these games when he remarks on how unnatural they were. "Women untrained to the rudis take their stand, daring, how recklessly, virile battles!" (Silvae, I.6.53).

Juvenal, a contemporary of Martial (XII.18), is especially critical of women from distinguished and illustrious families disgracing themselves in the arena or, for that matter, being enamored of gladiators and prizing them above home and country (Satires, VI. 82ff).

"What sense of shame can be found in a woman wearing a helmet, who shuns femininity and loves brute force....If an auction is held of your wife's effects, how proud you will be of her belt and arm-pads and plumes, and her half-length left-leg shin-guard! Or, if instead, she prefers a different form of combat [as a Thraex, both of whose legs were protected], how pleased you'll be when the girl of your heart sells off her greaves!....Hear her grunt while she practises thrusts as shown by the trainer, wilting under the weight of the helmet" (VI.252ff).

The desire for excitement and notoriety was such that several edicts were enacted to limit the participation of women in the arena, at least those who were not slaves or of low social status. Senators (but not equites) first were prohibited from fighting in the arena in 46 BC, when one had desired to compete as part of the games accompanying the dedication of Caesar's new forum (Dio, XLIII.23.5; Suetonius, XXXIX). There was another ban in 38 BC prohibiting senators (and their sons) from fighting as a gladiator (and appearing on stage) (Dio, XLVIII.43.3). In 22 BC, even the grandsons of senators could not appear on stage (Dio, LIV.2.5; Suetonius, Augustus XLIII.3). Performances in the arena were even more scandalous and must have been banned, as well.

Women, given their appearance on the stage, also were included for the first time. But this senatus consultum (senatorial decree) seems to have been ineffectual. Aristocratic women and equites continued to appear on stage and the ban was lifted (Dio, LVI.25.7). In AD 11, a degree declared that "no female of free birth of less than twenty years of age and for no male of free birth of less than twenty-five years of age to pledge himself as a gladiator or hire out his services <for the arena or stage>," a ban reiterated in AD 19. When Caligula came to the throne in AD 37, these prohibitions were of no significance. "He caused great numbers of men to fight as gladiators, forcing them to contend both singly and in groups drawn up in a kind of battle array. He had asked permission of the senate to do this, so that he was able to do anything he wished even contrary to what was provided by law" (Dio, LIX.10.1-2).

In 200 AD, Septimius Severus banned any female from the arena. During a gymnastic contest, "women took part, vying with one another most fiercely, with the result that jokes were made about other very distinguished women as well. Therefore it was henceforth forbidden for any woman, no matter what her origin, to fight in single combat" (Dio, LXXVI.16).

There is no specific Latin word for a female gladiator nor was there a feminine form, gladiatrix being a modern construction, first used in a translation of Juvenal in 1802. The closest term to identify the female gladiator is ludia (from ludus, "stage performer") but even that word tends to refer to the wife or lover of a gladiator.

When Tacitus writes of the "women of rank" (Annals, XV.55) who appeared in the amphitheater, he uses the word feminae, the respectable wives and daughters of Roman citizens. Mulier is used by Juvenal to describe the woman who shamelessly shuns her femininity and practices to be gladiator and by Petronius to describe the essedarius. A distinction was made, therefore, between the lady who does not willingly debase herself in entertaining the mob in the arena, and the woman who does. But neither was ever called a gladiator, although both femina and mulier were used of necessity.

"And sometimes it chanced that someone had specified in his will that the most beautiful women he had bought must fight among them, and even someone else had ordered that two boys, his favourites, must do that."

Nicolaus of Damascus, Athletica (IV.153)

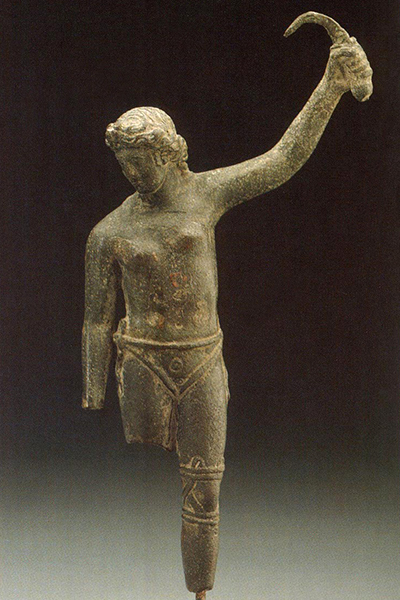

Manas has proposed that this small bronze statuette—the figure wearing only a loincloth and her knee wrapped in leather straps—is the only other representation of a female gladiator. Rather than an athlete using a strigil used to clean her body, as previously supposed, she is said to be holding a sica, a short sword with a curved or angled blade that was the traditional weapon of the Thraex. And, indeed, it does seem more appropriate that such a weapon would be triumphantly held aloft than an item of personal hygiene. Admitting that the helmet could have been put aside and the shield discarded after victory was won, it still is odd that there are not the greaves that the Thraex normally would wear.

The hair also is a curiosity. Slaves normally had their hair cut short (cf. Nero, who had the hair of his concubines "trimmed man-fashion," Suetonius, Life of Nero, XLIV.1) but the statuette has long hair. Manas argues that, since a free-born woman would not perform in public with her breasts exposed, that a slave must be represented—but one with long hair.

The marble relief from Halicarnassus in Turkey dates from the second century AD. Now in the British Museum, it depicts two women, Amazon and Achillia, fighting as gladiators. The Greek declares them missae sunt, that they both have received missio and been granted a reprieve from this particular contest.

Although heavily armed in the manner of the secutor, with greaves and the right arm protected and carrying a large oblong shield, the heads of the women are bare (as are their breasts). The absence of helmets is a curious omission and may be due simply to the desire to see the faces of the combatants, given the rarity of such encounters and how evenly matched were the protagonists. Coleman, however, suggests that the two round objects on either side of the names represent, not spectators but helmets, signifying that each combatant has qualified for missio.

Achilles is said to have killed and then fallen in love with Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, her beauty conquering the conqueror (Propertius, Elegies III.11). The noms de guerre of the two women, therefore, seem especially appropriate and one wonders if they were chosen deliberately.

References: "Female Gladiators in Imperial Rome: Literary Context and Historical Fact" (2008) by Anna McCullough, Classical World, 101(2), 197-209; "Female Gladiators of the Ancient Roman World" (July 2003) by Steven Murray, Journal of Combative Sport [electronic journal]; "Female and Dwarf Gladiators" (2004) by Stephen Brunet, Mouseion, 4, 145-170; "Missio at Halicarnassus" (2000) by Kathleen Coleman, in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 100, 487-500; "The Senatus Consultum from Larinum" (1983) by Barbara Levick, in The Journal of Roman Studies, 73, 97-115; Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy (1913) translated by A. S. Way (Loeb Classical Library); Juvenal: The Satires (1991) translated by Niall Rudd; "New Evidence of Female Gladiators: The Bronze Statuette at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe of Hamburg" (2011) by Alfonso Manas, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 28(18), 2726–2752.

See also Thraex.