Some of the most vivid depictions of gladiatorial and animal contests are to be found, not in Rome, but on the edge of empire—in Germania Superior, outside the spa town of Bad Kreuznach. Originally a Celtic settlement on the River Nahe, in the first-century BC it became a Roman vicus or village. Three centuries later, a sumptuous villa was constructed there, its mosaic floors masterpieces of the art.

The Nahe flows below the slopes of the Hunsrück and joins the Rhine at Bingen about nine miles downstream. On the other side of this upland ridge, wending its way through low hills, is the Moselle, its waters immortalized by the Latin poet Ausonius in the Mosella.

"Thy flood moves softly and thy waters limpid-gliding reveal in azure light shapes scattered here and there: how the furrowed sand is rippled by the light current, how the bowed water-grasses quiver in they green bed: down beneath their native streams the tossing plants endure the water's buffeting, pebbles gleam and are hid, and gravel picks out patches of green moss....Yon is a sight that may be freely enjoyed: when the azure river mirrors the shady hill, the waters of the stream seem to bear leaves and the flood to be all o'ergrown with shoots of vines. What hue is on the waters when Hesperus has driven forward the lagging shadows and o'erspreads Moselle with the green of the reflected height! Whole hills float on the shivering ripples: here quivers the far-off tendril of the vine, here in the glassy flood swells the full cluster" (60ff, l89ff).

Displayed in what likely was the dining room (triclinium) of the villa, the tessellae of the Oceanus Mosaic (bottom left) proudly spell out Victorinvs·Tess<ellarius>·Fec<it> ("Victorinus, mosaicist, made this"). Another inscription, obscured in the shadows of the right-hand corner, reads Maximo·et·V<rbano consulibus>, which dates the mosaic to AD 234, when Maximus and Urbanus held the Roman consulship.

Oceanus himself, hidden behind the fountain in the apse, is shown with crab claws sprouting from his forehead to signify the god's dominion over the sea and its creatures. More dramatic still is the Gladiator Mosaic.

"About the panthers, the business is being carefully attended to according to my orders with the aid of those who hunt them regularly; but it is surprising how few panthers there are; and they tell me that those there are bitterly complain that in my province [Cilicia, on the eastern coast of Turkey] no snares are set for any living creature but themselves; and so they have decided, it is said, to emigrate from this province into Caria [farther west along the coast]."

Cicero, Letters to Friends (II.xi)

A day at the gladiatorial games (munera) began in the morning with the venatio (Latin, "hunt"). Here, a professional venator, wearing only a tunic and leg wrappings, holds a hunting spear (hasta) in both hands. He has just impaled a charging leopard—the exotic animal symbolic of the emperor's far-reaching power over nature. Other mosaics in the series show combat with bulls, bears, and boars (cf. Martial, "Each new day gives us at morn conflicts more great. How many massive beasts, heavier than Nemea's monster [the Nemean lion, killed by Hercules as his first labor], are laid low! How many Maenalian boars [Hercules' fourth labor] does thy spear expose in death!" Epigrams, V.65).

Dating to the late first-century AD, this beautifully preserved fresco shows a venator confronting a Barbary lioness. It once adorned the podium of the amphitheater at Augusta Emerita (Mérida, Spain), where it is in the National Museum of Roman Art. Notice the small crossbar just behind the spear head, which prevented it from penetrating too deeply into the animal—and either getting stuck there or allowing the enraged beast to drive itself back up the shaft. Coincidentally, the "first physical evidence for human-animal gladiatorial combat from the Roman period seen anywhere in Europe" was published in 2025. A skeleton was found in a cemetery outside Eboracum (York, England) showing evidence of bite marks by a big cat, most likely a lion—the only remains to have been discovered with such injuries.

"...after military standards had first entered, two horsemen would come out, one from the east side and the other from the west, on white horses, bearing small gilded helmets and light weapons. In this way, with fierce perseverance, they would bravely enter combat, fighting until one of them should spring forward upon the death of the other, so that the one who fell would have defeat, the one who slew, glory."

Isidore of Seville, Etymologies (XVIII.liii)

In the afternoon, gladiatorial combat was introduced by the eques. Although the word means "horseman," the combatants usually are depicted in the final, decisive stage of their dual—fighting on foot, after having dismounted and discarded their spears. He can be distinguished by a loose fitting belted tunic and a plain brimmed helmet decorated by feathers fitted into sockets on either side, a medium-sized round shield (in imitation of the cavalry) and a short, straight sword. The right arm was protect with a manica ("sleeve") of thick quilting or overlapping metal scales, and the legs by short gaiters or wrappings. Because the eques always fought against his own kind (the only category of gladiator, other than the provocator, to do so), the tunics (or shields) were of different colors so spectators could tell them apart.

Named after the Thracians, a barbarian tribe encountered by the Romans in its war against Mithridates VI, a thraex lunges at his opponent, having thrown aside his shield. Like the Illyrians and Dacians (whose homeland was the Balkan Peninsula), he carries a sica, a short sword native to the region that curved upward, allowed a thrusting strike around a shield to the exposed side or back. Given the small size of his own square convex shield (parmula), the thraex protected his sword arm and shoulder with a manica, the exposed legs by high greaves (ocreae) that reached almost to mid-thigh, and quilted padding up to the hips. A heavy leather belt (balteus) worn above the loincloth (subligaculum), offered some protection to the bare torso. Characteristically, the brimmed helmet was surmounted by the figure of a griffin, the companion of Nemesis, goddess of fate and judgment. Intriguingly, this thraex is left-handed, a rarity that offered a advantage when confronting a gladiator who had been trained to fight right-handed and so carried the shield on the left—completely exposing his right side. Another curiosity is that the contest seems to be ad mortem which, given the expense of training and maintaining a skilled gladiator, was atypical.

Traditionally (and most frequently in the first-century AD), the thraex was paired against the murmillo, here likely to suffer a fatal blow. Named after the Greek word for a type of fish with a prominent dorsal fin, his brimmed helmet was distinguished by its deep visor and high angular crest. Like the thraex, he wore a loincloth and belt, and a manica on his right arm—but carried (like the legionary) a large rectangular shield (scutum) that curved around the body. Reaching to the chin and overlapping the greaves at the ankles, it almost completely protected the body. The greaves were much shorter as a result, with only additional padding for the shins. The weapon of the murmillo was the gladius, a sword of medium length with a broad straight blade that, like the shield, was standard legionary issue. In this contest, one appreciates (as did the Romans themselves) the strengths of each combatant: the more lightly protected but nimble thraex with his deadly sica against the heavily armored but ungainly murmillo, whose shield and armor could weigh as much as forty pounds. Presumably, contests were short enough that the combatants did not die from exhaustion or heat prostration.

This Ephesian marble relief is not at Römerhalle but the Antikensammlung ("Antiquities Collection") in Berlin. It shows the murmillo Asteropaios ("Starry") delivering a fatal thrust just above the heavy balteus of Drakon ("Dragon"), a thraex whose own curved sica has not struck in time.

Notice how stocky and stout the combatants are. The extra weight is from a diet of sagina, a gruel of barley and beans that added a layer of subcutaneous fat to the body—and some protection to the vital organs within. Pliny, in fact, called gladiators hordearii ("barley men") because of the large amount of grain they consumed (Natural History, XVIII.xiv.72). A diet high in carbohydrates also is associated with lower bone density. To compensate for potential calcium deficiency, gladiators drank a potion of vegetable ash dissolved in water or wine to increase their intake of the mineral—as confirmed by Lösch et al. in a study of bones from a gladiator cemetery in Ephesus dating to the second and third century AD.

Galen, whose knowledge of anatomy derived from treating wounded and dying gladiators in Pergamon for four years (AD 158–161) remarks on the effects of faba beans mixed with barley water. "Our gladiators eat a great deal of this food every day, making the condition of the body fleshy"—and also causing flatulence (On the Properties of Food Stuffs, I.xix.529). And Pliny, quoting Varro, remarks "your hearth should be your medicine chest. Drink lye [water strained through wood ash] made from its ashes, and you will be cured. One can see how gladiators after a combat are helped by drinking this" (XXXVI.lxix.203).

Occasionally, the thraex was paired against the hoplomachus, so named because he was outfitted to resemble a heavily armed Greek hoplite. These gladiators can be confused with one another, as they all protected the right arm with a manica and the legs with quilted wrappings or high greaves. Each, too, wore a brimmed and visored helmet with a crest. But they had to have distinguishing characteristics if the audience were to tell them apart. Whereas the thraex carried a small almost square shield, the hoplomachus used a small round one and attacked with a spear. To compensate for the diminutive shield (which allowed the gladiator to hold a dagger as well), the legs were protected by quilted wrappings that extended from the waist to the ankles and were covered by high greaves—which offered protection against superficial wounds that would not be mortal but nevertheless could shorten the entertainment of the combat. The hoplomachus also could be paired against the murmillo, the small shield and spear of the one against the larger shield and sword of the other.

(In the latter part of the second-century AD, Marcus Aurelius remarks that he has learned not to favor the Greens or Blues in races at the circus nor "the Parmularius or the Scutarius at the gladiators' fights" (Meditations, I.5). He is distinguishing between two types of gladiators: the thraex and hoplomachus who used the smaller parmula (whether square or round), and the murmillo and secutor who used the large legionary scutum.)

"The net-fighter (

retiarius) is named for his type of weapon. In a gladiatorial game he would carry hidden from view a net (rete) against the other fighter; it is called a ‘casting-net’ (iaculum), so that he might enclose the adversary armed with a spear, and overcome him by force when he is tangled in it. These fighters were fighting for Neptune, because of the trident."Etymologies (XVIII.liv)

"The pursuer (secutor) is named because he pursues (insequi, ppl. insecutus) net fighters, for he would wield a spear and a lead ball that would impede the casting-net of his adversary so that he might overwhelm him before he could strike with the net. These combatants were dedicated to Vulcan, because fire always pursues. And the pursuer was matched with the net-fighter because fire and water are always enemies."

Etymologies (XVIII.lv)

This pairing

depicts a retiarius and a secutor. Unlike the heavily armed gladiators of foreign origin, the Retiarius or "net man" was not introduced into the arena until sometime after the mid-first century AD, becoming steadily more popular (if not as prestigious) in the centuries to follow. The most immediately recognizable of the gladiators, the Retiarius had no barbarian or military association and wore neither helmet nor greaves, shield or sword. Instead, his weapons were the trident and net, symbols of the sea. Equally distinctive was the prominent bronze guard (galerus) that was fitted to the manica and protected the upper arm and shoulder—and so high that the retiarius actually could turn his shoulder and duck his head partially behind it. The strategy was to cast the net gathered in his right hand and then spear his entangled foe with the trident that, together with a dagger, he held in his left. Invariably, the net could not be retrieved and the retiarius would have to rely on his long trident, with which he could parry blows and even leverage against the sword or shield of his opponent.

The secutor, whose equipment otherwise was similar to that of the murmillo, was distinguished by his unique helmet. Round and smooth, with a narrow brim and unadorned crest (intended to elicit the image of a fish's head), it was free of any decoration on which the trident might snag. The small eyeholes were the only openings in an otherwise suffocating mask—but necessary if they were not to be pierced by the thrusting prongs. Again, the adversaries were cleverly matched. The secutor wore padding and a single greave (ocrea) on the exposed left leg (which was placed forward in combat) and protected his right behind a tall curved shield. But the enclosed helmet made him almost deaf and blind. The retiarius had to avoid the flailing sword but, if he could strike while his opponent ducked his head or hid behind the shield, there was the chance of an unexpected attack. Failing that, the sheer exhaustion from carrying such heavy armor made the secutor increasingly vulnerable in extended combat.

At some point during the Roman occupation of what later was to become Germania Superior, the Celtic settlement of Cruciniac was renamed Cruciniacum, the Latin suffix -acum (Celtic -acon) signifying "place of" or "related to"—as it does with nearby Mogontiacum, the provincial capital, which was named after the Celtic god Mogon. It is not known when this actually occurred as the Roman vicus is not mentioned by name until centuries later when, in AD 819, a Carolingian palace was built on the site. In time, Cruciniacum was changed to Kreuznach, -nach being a common suffix of the region.

One assumes that Kreuz ("cross") derived from the Latin Crux. Popp argues, however, that Cruciniacum was not linked to a personal name (an anthroponym) nor with "cross" but to the features of the landscape itself, namely, the hilly terrain where it was situated. Rather than the etymology seemingly being obvious, it is "a toponymic paretymology," i.e., a false or folk etymology for a word whose origin is otherwise unknown.

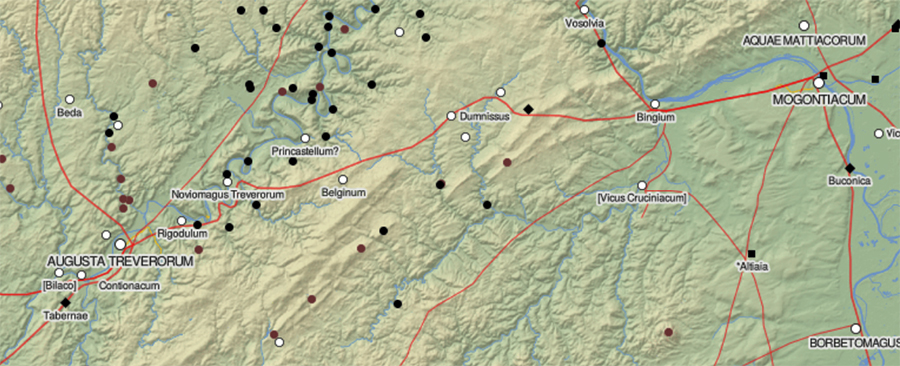

This detail is from the online Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire by Johan Åhlfeldt and hosted by the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. It show the topography of the region and the route taken in AD 368 by Ausonius along the Roman road from Bingium (Bingen) on the Rhine to Augusta Treverorum (Trier) on the Moselle, a distance of some seventy-five miles. (Trier takes its name from the Treveri, a local Celtic tribe, and Treverorum means "of or among the Treveri.")

"In the first place, he [the general] should have an exact description of the country that is the seat of war, in which the distances between places, the nature of the roads, the shortest routes, by-roads, mountains and rivers, should be correctly provided."

Vegetius, De re militari (III.vi)

This schematic is from the Tabula Peutingeriana, a early thirteenth-century copy of a fourth-century AD itinerarium of Rome's cursus publicus or public way. The route is in stages from Bingium to Dumno (Dumnissus), Belginum, Noviomagnus Treverorum, and Augusta Treverorum, the distance of each marked in Roman miles (curiously, the numbers add up to forty statute miles). Certainly, Vegetius, writing in the late fourth-century AD, would have approved of such a map.

In reading the Mosella, one would think that Ausonius walked to Trier by himself. In fact, he had been ordered to escort Gratian, the eight-year old son of Valentinian I, back to the imperial capital. No doubt, they made the journey by carriage and were accompanied by legionaries.

In Bingen, he "gazed with awe upon the ramparts lately thrown round ancient Vincum [another name for the town]" (2) which had been fortified a decade earlier (in AD 359) by the emperor Julian in preparation for renewed war with the Alemanni (Ammianus Marcellinus, The History, XVIII.2.4). From there, he trekked over the Hunsrück, "a lonely journey through pathless forest, nor did my eyes rest on any trace of human inhabitants" (5) and then to Dumnissus, "sweltering amid its parched fields" (8), Tabernae "watered by its unfailing spring," (8), and Noviomagus Treverorum (Neumagen) "the famed camp of sainted Constantine" (11), which had been occupied by the emperor in defending Gaul against the Franks and Alemanni (AD 306–312). There, Ausonius reached the Moselle, with its "roofs of country-houses, perched high upon the over-hanging river-banks, the hill-sides green with vines, and the pleasant stream of Moselle gliding below with subdued murmuring" (20–22).

Following the river, he finally arrived at Augusta Treverorum (Trier), the regional capital—and its amphitheater. Constantine had captured two of the Frankish chieftains early in the war who, "on exhibiting a magnificent show of games, he exposed to wild beasts" (Eutropius, Abridgment of Roman History, X.3). Panegyrics to Constantine praise the emperor for his victory: "When the fierce kings Ascaricus and his associate [Merogaisus] had been captured you inaugurated your martial endeavors with so much acclaim that we considered it a guarantee of unheard-greatness....so you, Emperor, in the very cradle of your rule, as if you were slaying twin dragons, amused yourself with the celebrated punishments of savage kings" (Panegyrici Latini, IV.16.5–6; also VI.10.1–2 and VII.4.2). In a campaign in AD 308, "Countless numbers were slaughtered, and very many were captured. Whatever herds there were were seized or slaughtered; all the villages were put to the flame; the adults who were captured...were given over to the amphitheater for punishment, and their great numbers wore out the raging beasts" (VI.12.3).

Just upstream from Bingen was Mogontiacum, a military camp where Legion XXII Primigenia was stationed. In March AD 235, resentful that Alexander Severus had submitted to his domineering mother in appeasing the Germanic tribes, the emperor was assassinated (Historia Augusta: Life of Severus Alexander, LXII.5; Herodian, Roman History, VI.9.6ff). In his place, Maximinus Thrax was acclaimed, the first emperor of barbarian origin—and reputed to be over eight feet tall (Historia Augusta: The Two Maximini, VI.8, XXVIII.8).

The death of Alexander, who was the last of the Severan dynasty, precipitated half a century of civil unrest and economic upheaval (the so-called Crisis of the Third Century). One can only wonder how the wealthy owner of the sumptuous villa on the Nahe, his magnificent mosaic of Oceanus having been completed only the year before, negotiated these tumultuous times.

References: Gladiators and Caesars (2000) edited by Eckart Köhne and Cornelia Ewigleben; "An Ancient (Celtic) Topnymic Crux: The Origins of the Name of Bad Kreuznach–Cruciniacum" (2019) by Antonia Maria Popp and Francesco Perono Cacciafoco, RHGT: Review of Historical Geography and Toponomastics, XIV(27-28), 49-66; The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (2006) translated by Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof; Cicero: The Letters to His Friends (Vol. I) (1927) translated by W. Glynn Williams (Loeb Classical Library); Ausonius (Vol. I) (1919) translated by Hugh G. Evelyn White (Loeb Classical Library); In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panegyrici Latini (1994) translated by C. E. V. Nixon and Barbara Saylor Rogers; Roman Trier and the Treveri (1971) by Edith Mary Wightman; Flavius Vegetius Renatus: The Military Institutions of the Romans (1767/1944) translated by Lt. John Clark; Martial: Epigrams (Vol. I) (1919) translated by Walter C. A. Ker (Loeb Classical Library); "Unique Osteological Evidence for Human-Animal Gladiatorial Combat in Roman Britain" (2025, April 23) by T. J. U. Thompson, D. Errickson, Christine McDonnell et. al., PLOS One (online); "Stable Isotope and Trace Element Studies on Gladiators and Contemporary Romans from Ephesus (Turkey, 2nd and 3rd Ct. AD)—Implications for Differences in Diet" (2014, October 15) by Sandra Lösch, Negahnaz Moghaddam, Karl Grosshmidt et al., PLOS One (online).

See also Nennig.