The Library at Pergamon

"The Attalic kings, stimulated by their great love for philology, having established an excellent public library at Pergamum, Ptolemy, actuated by zeal and great desire for the furtherance of learning, collected with no less care, a similar one for the same purpose at Alexandria, about the same period."

Vitruvius, On Architecture (VII, Preface 4)

Pliny, too, speaks of the rivalry between Ptolemy V Epiphanes ("God Manifest") and Eumenes II Soter ("Savior") of Pergamon in Asia Minor, and their respective libraries. When Ptolemy prohibited the export of papyrus, parchment (charta pergamena) was said to have been invented in Pergamon as a substitute. "After this, the use of that commodity, by which immortality is ensured to man, became universally known" (Natural History, XIII.xxi.70). According to Herodotus, however, animal skins already had been a writing material for hundreds of years and used whenever there was a scarcity of papyrus (Histories, V.58.3). Ptolemy also is said to have imprisoned Aristophanes of Byzantium, librarian at Alexandria and a teacher of Aristarchus of Samothrace (who succeeded him in that role) when he was suspected of leaving for the court of Eumenes (Suda, alpha 3936).

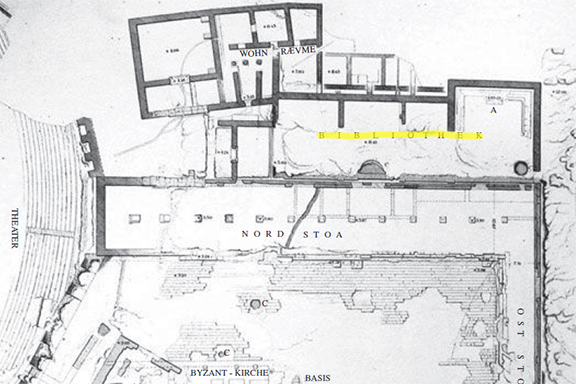

The first description of the sanctuary of Athena Polias Nikephoros ("Athena, Protector of the City and Bringer of Victory") was a survey by Richard Bohn published in 1885. In the second volume of a series on the Altertümer von Pergamon ("The Antiquities of Pergamon"), he presented a ground plan that shows the upper level above the sacred precinct of the Temple of Athena. There, Bohn identified four rooms, fronted by a two-story colonnaded stoa, which he presumed to have contained the royal library. The largest of these rooms and the best preserved has a small base (A) projecting from the wall which he understood to have served as a plinth for a monumental statue of Athena found there (below). A regular series of holes in the walls also suggested to him that the hall served a book depository and reading room, while the other three rooms were book stacks.

Later scholars, however, have proposed that the space may have been a reception or banquet hall—or, given that it is located within the sanctuary, a repository or storeroom for offerings or even an exhibition room to display dedications to Athena. It therefore is not certain that the rooms originally thought to have been the location of the Pergamon Library actually served that purpose.

In this satellite view of the upper terrace, the long shadow over the tiers of the theater are cast by a later Byzantine watch tower, the others by trees.

As with the libraries, so their directors were rivals as well. Crates of Mallus (in Cilicia) was a director of the Library of Pergamon, where he founded a school of linguistic criticism. His teachings gained popularity in Rome when, as an envoy to the Senate in about 169 BC, he fell into a sewer opening and broke his leg. It was while recuperating that he lectured and held seminars, thereby becoming "the first to introduce the study of grammar into our city" (Suetonius, De Grammaticis, II).

Strabo considered Aristarchus and Crates to be "the leading lights in the science of criticism." But to his exasperation they approached Homer differently. "The poet says: 'the Ethiopians that are sundered in twain, the farthermost of men' [Odyssey, I.22-23]. About the next verse there is a difference of opinion, Aristarchus writing: 'Abiding some where Hyperion sets, and some where he rises'; but Crates: 'abiding both where Hyperion sets and where he rises.' Yet so far as the question at issue is concerned, it makes no difference whether you write the verse one way or the other" (Geography, I.2.24). In the Loeb translation of Homer, the line regarding the abode of the Ethiopians on the Ocean shore is, in fact, that of Aristarchus.

While in Greece, Aulus Gellius, a second century AD Roman grammarian, compiled a miscellany for the edification of his children. "Now two distinguished Greek grammarians, Aristarchus and Crates, defended with the utmost vigour, the one analogy, the other anomaly. The eighth book of Marcus Varro's treatise On the Latin Language, dedicated to Cicero, maintains that no regard is paid to regularity, and points out that in almost all words usage rules" (Attic Nights, II.25.4-5).

This is the passage to which Gellius was referring: "Certain writers express the idea that in speaking men ought to follow those words and forms which are derived in similar fashion from like starting points—which they call the products of Analogy; and others are of opinion that this should be disregarded and rather men should follow the dissimilar and irregular, which is found in ordinary habitual speech—which they call the product of Anomaly. But in my opinion we ought to follow both, because in voluntary derivation there is Anomaly, and in the natural derivation there is even more strikingly Regularity [Analogy]" (On the Latin Language, VIII.ix.23, also IX.i.1).

Aristarchus, in other words, championed the notion of analogy in studying the formal structure of language and the regularity of its principles. Crates argued that words and the things they describe sometimes do not have such a regular relationship but, like irregular declensions and conjugations, were anomalous.

But Crates could indulge in allegorical exegesis as well—as when he interpreted Homer's vivid description (ekphrasis) of Agamemnon's shield in the Iliad (XVIII.558–709) as a representation of the cosmos itself, philosophical or scientific truth being expressed poetically. A cosmologist himself, it is not surprising that Crates constructed the first globe of the earth (Strabo, Geography, II.5.10). The torrid zone circling the equator was occupied by the Ocean, which divided the temperate zones above and below the equator, with Ethiopians living in both hemispheres (I.2.24). For Strabo, all this was annoyingly pedantic, with the two rival grammarians indulging in "a petty and fruitless discussion of the text." Athenaeus agreed, dismissing "the sons of Aristarchus...buzzing in corners, mumbling monosyllables, whose sole business is the difference between 'ye' and 'your' and 'it' and 'hit'" (Deipnosophistae, V.222A)

After ruling for almost forty years (197–159 BC), Eumenes was succeeded by his son Attalus III (138–133 BC) who, upon his death, bequeathed Pergamon and his kingdom to Rome, believing that it would be conquered in any event (Strabo, XIII.4.2). When Caesar's assassins were defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, Antony remained behind to rule in the East. His domain included Pergamon, "by far the most famous city in Asia" (Pliny, V.xxxiii.126). The next year, he was said to have given its Library of 200,000 scrolls to Cleopatra (Plutarch, Life of Antony, LVIII.5) —the year after that, she gave him the Sun and the Moon, the names of their twin children.

In appreciation for having studied philosophy in Athens, Attalus II (159–138 BC, the brother of Eumenes) bestowed upon the city a stoa, a long two-story colonnaded portico that protected the shops in the Agora and became its main commercial center. Using surviving remnants, the Stoa was recreated on its original foundation and dedicated in 1956. It now houses the Museum of the Ancient Agora—and conveys a sense of the northern stoa that fronted the Library.

This statue is a copy of the chryselephantine cult statue of Athena Parthenos by Phidias in the Parthenon (which takes its name from the goddess's epithet) and was situated in the great hall of the stoa. It now is in the Pergamon Museum (Berlin), where it has been placed in front of the façade of the Temple of Zeus Sosipolis ("Savior of the City") from Magnesia on the Maeander (Strabo, XIV.41).

In the photograph of the ruins (top), the Library is thought to have occupied a large room, now dark rubble, in the right background. The picture was taken just outside the northern stoa in the sacred precinct surrounding the sanctuary of Athena Polias Nikephoros.

References: "Where Was the Royal Library of Pergamum: An Institution Found and Lost Again" by Gaëlle Coqueugniot, in Ancient Libraries (2013) edited by Jason König, Katerina Oikonomopoulou, and Greg Woolf (pp. 109-123); Pergamon Citadel of the Gods: Archaeological Record, Literary Description, and Religious Development (1998) edited by Helmut Koester; Altertümer von Pergamon 2: Das Heiligtum des Athena Polias Nikephoros (1885) by Richard Bohn. Most of the literature relating to the Library of Pergamon is in German, however.

See also The Altar of Zeus.

![]()