Only two Bf 110s survived the war relatively intact. One was a Bf 110F-2, which is displayed in the Deutsches Technikmuseum (German Museum of Technology), Berlin. Stationed in Finland, the plane was one of four in a Schwarm that attacked a Russian train on the Murmansk-Leningrad line in January 1943. (One can see the fitting for a ventral gun pod or two 500 kg bombs.) Hit by anti-aircraft fire, the damaged plane was forced to land on a frozen lake near the Finnish border as it attempted to return to base. Abandoned by the crew, who were rescued the next day, it later sank when the ice melted.

In 1991, almost half a century later, the plane was recovered and then, after a sojourn in New Zealand, acquired in 1997 by the Museum, which restored it using parts from another downed aircraft. The Bf 110 had belonged to 13.(Z)/JG 5: Zerstörergruppe 13 of Jagdgeschwaders 5, Eismeer ("Ice Sea") and coded LN+NR. The dachshund (Dackel) on the nose signified that it also was part of a Dackelstaffel. In its jaws, the dog holds a stubby Polikarpov I-16, a mainline Russian fighter that, although innovative at the time of its introduction, had become obsolete when the Germans invaded in 1941.

Now in the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon, this Messerschmitt (Werknummer 730301) is identified by the Museum as a Bf 110G-4/R6 that served with 1./NJG 3, a Nachtjagdgeschwader or night-fighter unit in Denmark. The G-4 was the last production model Bf 110, the 1,850 planes that were built comprising fully one-third of the total number. This one was surrendered to the British in May 1945.

Ferried to England for evaluation, by August 1946 it had been selected for preservation and storage as a museum aircraft. Almost thirty year later, the plane was completely restored, repainted, and given its original code D5+RL. Most characteristic of the G-4 is the SN-2c Lichtenstein search radar (designated FuG 220 by the Germans, Funk Gerät or "radio set"). This antenna array, called Hirschgeweih ("stag's antlers"), was impressive but produced significant drag and reduced the plane's top speed.

There is some disagreement as to the variant of D5+RL however. The RAF Museum describes the plane as a R6. Rüstsatzen (arming or preparation kits) were adaptations designed to be installed after manufacture, either by special units or in the field. R6 redesignated two such Rüstsatzen: R2 and R3. The first was GM-1 (Göring Mischung, "Göring Mixture") in which nitrous oxide was injected through the supercharger intake to provide additional oxygen to the engines at high altitude, briefly increasing their performance by 300 hp. But the heavy tank of super-cooled liquid shifted the center of gravity rearward, making the plane more difficult, even dangerous, to fly. It also required that the rear MG 81Z machine gun be removed—and its gunner. The loss of a third crewman (and an extra pair of eyes) no doubt was resented. Nor was a boost in speed even thought to be necessary, since the British Mosquito, which the adaptation was designed to combat, did not operate at altitudes above 8,000 meters (about 26,000 feet). For all these reasons, the R2 system was considered useless by pilots in the field and often removed, if only because supplies of nitrous oxide often were not even available.

Rüstsatz 3 was less controversial. It was the replacement of the four nose-mounted MG 17 7.92mm guns with twin 30mm MG 108 cannons, a configuration installed so often that it came to be regarded as standard equipment. Staggered to allow clearance for the ammunition boxes, the starboard gun had to be moved forward so that its muzzle protruded from the nose of the plane. The two MG 151 20mm cannons on the underside were more recessed, almost at the wing spar, their barrels firing through long blast tubes. Hopp, one of the first to write about the plane in detail, identifies it simply as an R3, but the access port to the nitrous oxide filler pipe located just behind the weapons bay, although easily overlooked, shows the plane to be a R6.

Auxiliary under-wing drop tanks each held 300 liters of fuel and provided additional range (B2 modification), and there was an attachment for mounting either two 500 kg bombs (however impractical they would be in air-to-air combat) or a ventral gun pod that held two additional 20mm MG 151 guns (M2 modification). Usually, a plane's designation was limited to a single adaptation, even if additional auxiliary equipment was installed—R6, for example, instead of R2/R3/B2/M2.

Some descriptions of D5+RL indicate that the plane was fitted with Schräge Musik, two fixed MG FF 20mm cannons that fired obliquely upward at the vulnerable underside of enemy bombers. If so, its designation would be R8. But they have been confused with the MG 81Z 7.92mm machine guns that occupied almost the same position at the rear of the cockpit.

More problematic is whether D5+RL was attached to 1 Staffel or to 3 Staffel, as Hopp contends. The apparently white spinner hubs are the color of 1 Staffel (in fact, they match the color of the plane itself), but the unit code is "L," which signifies that the plane belonged to 3 Staffel, in which case, the hubs should be yellow—as early color photographs of the plane attest. (The yellow aft fuselage band, however, was applied to all Zerstöreren in defense of the Reich.)

The camouflage scheme of RLM 75 gray waves (Wellenmuster) over RLM 76 white blue (Weissblau) may not seem sufficiently dark for a night fighter. But some reflective light is retained on even the darkest nights, and a completely black plane (such as GA+G9, one of the earliest night fighters) was found to be silhouetted against the sky, and lighter colors were introduced in 1944 to lessen the contrast.

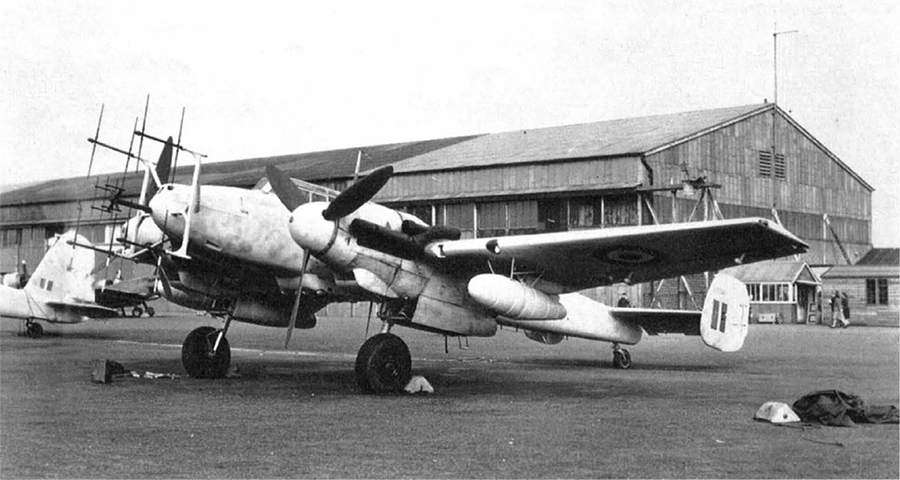

In this photograph of another war prize (WNr. 730037) on exhibit at Farnborough in late 1945, the flame dampers over the engine exhausts are readily apparent, as is the FuG 212 and SN-2b Lichtenstein radar array. Short-range performance of the newly-developed SN-2 radar initially was so poor, however, that the older FuG 212 (the smaller central array of aerials) had to be retained.

The following planes have been profiled because of their historical or pictorial interest:

References: Individual History: Messerschmitt Bf 110G-4/R6 (2018) by Andrew Simpson (Royal Air Force Museum); War Prizes (1994) by Phil Butler (pp. 84-85); Messerschmitt Bf 110 Zerstörer Aces of World War 2 (1999) by John Weal (p. 51); Messerschmitt Bf 110 Nightfighters (n.d.) by Alfred Price (pp. 52, 58-59); Bf 110G (2000) by Ron Mackay; Messerschmitt Bf 110/Me 210/Me 410: An Illustrated History (2003) by Heinz Mankau and Peter Petrick (pp. 217, 226); Monogram Close-Up 18: Bf 110G (1986) by George C. Hopp (pp. 15-18ff); Messerschmitt Bf 110 (1998) by Shigeru Nohara and Masato Tanaka.