"Myron, who almost captured the souls of men and animals in his bronzes..." Petronius, Satyricon

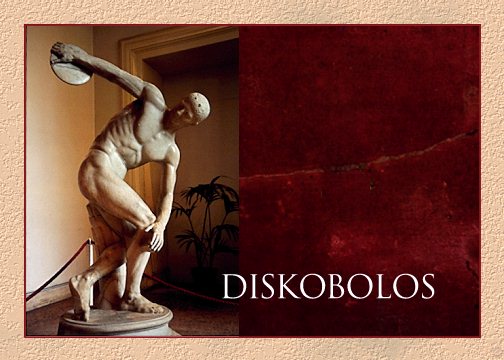

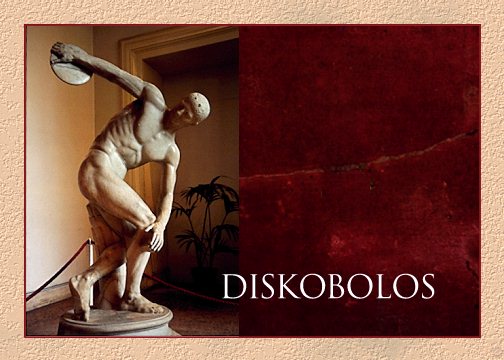

Although Myron was renown in antiquity for a bronze heifer so realistic that it could be mistaken for an actual cow, it is the "Discus Thrower" for which he is most famous. A Roman copy of a mid-fifth century BC bronze, it exemplifies the Greek sense of harmony and balance (rhythmos) which Pliny praises.

"Myron is the first sculptor who appears to have enlarged the scope of realism, having more rhythms [rhythmos] in his art than Polycleitus and being more careful in his proportions [symmetria]. Yet he himself so far as surface configuration goes attained great finish, but he does not seem to have given expression to the feelings of the mind, and moreover he has not treated the hair and the pubes with any more accuracy than had been achieved by the rude work of olden days."

Symmetria is the commensurability of parts, all in balanced and harmonious proportion, which is so well exemplified in the Discobolos. The athlete is in equilibrium, posed just before releasing the discus, the parts of his body in dynamic counterbalance. The head, however, seems almost to be a separate bust, so passive is its expression.

In his Institutio Oratoria (Training of an Orator), Quintilian, who wrote in the first century AD, compares the rhetorician and the artist, and the distinguishing personal style that makes each unique. Interestingly, his scheme of the evolution of sculpture is different from that of Pliny. A stage of "softness" is attained by Myron, with a high point realized in the work of Polyclitus and Pheidias, after which decline sets in.

"What work is there which is as distorted and elaborate as that Diskobolos of Myron? But if anyone should criticize this work because it was not sufficiently upright, would he not reveal a lack of understanding of the art, in which the most praiseworthy quality is this very novelty and difficulty?"

"'Do you mean the discus-thrower,' said I, "the one bent over in the position of the throw, with his head turned back toward the hand that holds the discus, with one leg slightly bent, looking as if he would spring up all at once with the cast?' 'Not that one,' said he, 'for that is one of Myron's works, the discus-thrower you speak of.'"

Lucian, Philopseudes (The Lover of Lies)

It is literary descriptions such as this that allow the Discobolus to be identified and attributed, of which the marble copy pictured above is the most complete example and the only one to correctly position the head (the copies in the British Museum and the Vatican, for example, depict the head facing away from the throwing arm).

The small knobs on the forehead were used to fit a device in making the copy.

References: The Art of Ancient Greece: Sources and Documents (1990) by J. J. Pollitt; The Oxford History of Classical Art (1993) edited by John Boardman; Pliny: The Natural History (1938) translated by H. Rackham (Loeb Classical Library); Lucian III: The Lover of Lies (1916) translated by A. M. Harmon (Loeb Classical Library); Quintilian: Training of an Orator (1920) translated by H. E. Butler (Loeb Classical Library); Petronius: The Satyricon and the Fragments (1965) translated by John Sullivan (Penguin Classics).