"He also built Liburnian galleys [after an Illyrian people living in Dalmatia] with ten banks of oars, with sterns set with gems, particoloured sails, huge spacious baths, colonnades, and banquet-halls, and even a great variety of vines and fruit trees; that on board of them he might recline at table from an early hour, and coast along the shores of Campania amid songs and choruses. He built villas and country houses with utter disregard of expense, caring for nothing so much as to do what men said was impossible."

Suetonius, Life of Caligula (XXXVII.2)

Local fishermen, their weighted nets snagging on sunken hulls, knew that two ships rested at the bottom of Lake Nemi, a placid water-filled caldera just south of Rome. It then belonged to Cardinal Prospero Colonna whose fiefdom included the fortified medieval towns of Nemi and Genzano nestled opposite one another high on the wooded rim. A nephew of the pope and Renaissance humanist (he once had owned the Belvedere Torso so admired by Michelangelo), Colonna was intrigued by the fragments of timber being brought to the surface and curious why such ships even should have been there. The inhabitants, who collectively had tried to remove the obstacles themselves, no doubt appealed to the cardinal for help as well.

In 1446, he commissioned the architect and engineer Leon Battista Alberti to direct the recovery of the ship nearer shore. He briefly mentions it in De re aedificatoria ("On the Art of Building"), "which while I was writing this Treatise was dug up out of the lago di Nemi," remarking only that he managed to pull up pieces of pine (fir) and cypress, which "had lasted extremely well" given that they had been under water for what he thought to have been more than thirteen-hundred years. They were caulked in a double layer of linen soaked in pitch and protected by sheets of lead fastened by brass nails (V.12). He may have said more in De navis, a short treatise on ships that is mentioned by Leonardo da Vinci, but the manuscript never was published and now is lost.

The earliest reference to the Nemi ships is a letter written two years earlier by his friend, the historian Biondo Flavio. He had recommended Alberti to the cardinal and even may have witnessed the recovery himself—which he recounts in Italia Illustrata (II.47–50), a work on the cultural history and ancient place names of Italy (written when he had fallen out of papal favor, having been apostolic secretary, and was seeking new patronage). By lashing together rows of empty wine barrels, a large floating raft was constructed to support hoists and winches suspended over both sides. Professional free-divers hired from Genoa, "more like fish than men" and renown for their ability, then affixed iron grappling hooks to the wreck. With a great throng on shore and "all the fine minds of the Roman Curia" looking on, the intention was to salvage the entire ship. But, unaware of the hulk's massive size, only a small section of the bow was lifted from the muddy silt, the rest tearing away as it was brought to the surface. (Interestingly, Biondo uses the analogy of planks hauled ashore from a wrecked ship to justify any perceived deficiencies in his treatise. If a lost ship cannot be recovered in its entirety, better at least that some portion be saved, Preface, 4.)

Rather than pine and cypress, Biondo thought the ship to be made entirely of larch, the planks three digiti thick. Indeed, the Romans prized the superiority of larch, long lasting and "not rotting with age." More importantly, it "will neither burn nor char, nor, in fact, suffer any more from the action of fire than a stone" (Pliny, Natural History, XVI.xix.43, 45; Vitruvius, On Architecture, II.ix.14.). They were joined by bright bronze nails almost eighteen-inches long, "so well-preserved and shiny that they seem to have just come from the blacksmith's anvil," caulked with silken fabric soaked in pitch (bitumen), and entirely clad in sheets of lead.

The interior was said to be coated with an application of clay and chalk over which molten iron had been poured and then another coating applied, fusing everything together in an impermeable fireproof layer several inches thick so that "the iron ship (so to say) became as big as the one of larch before it." It is a confused account, given that the hulls do not display any such configuration, and Biondo may be commenting on the base layer for a mosaic pavement. Yard-long sections of interlocking lead pipes connecting the ship to the shore were discovered as well, which he says Alberti thought to have conveyed water from a spring below Nemi. "Elegant letters were inscribed on each of them to indicate, so I thought, that the emperor Tiberius was the creator of the ship." Alberti had attributed it to Trajan, although he does not say why; in fact, there are no such attributions.

Pius II (1458–1464), having commended Alberti as "a scholar and a very clever archaeologist" (Commentaries, XI.187), journeyed to Nemi to see for himself "the ship which in our day has been found in the lake" (XI.190). This was in 1463, two months after the death of Colonna and a month before that of Biondo. The pope speaks of a single broken piece of hull being made of larch two inches thick, smeared with pitch covered with reddish silken cloth and overlaid with lead plates secured by bronze nails, "their gilded heads set so close together that no water could get in." And he repeats Biondo's remark on the inner surfaces having a thick coating of iron and clay to protect against fire but admits that it is "a process our experts do not understand"—as well as the mysterious inscription tiberius caesar on the lead pipes. But he also adds that divers reported seeing a chest girded by hoops and a clay water jar with a gilded-bronze lid, which no doubt reinforced in Pius' mind that the palatial vessel was similar to contemporary pleasure craft he had seen for himself. Beams "made of larch wood which is very like fir" that had been recovered by Alberti and abandoned on shore were inspected as well "with a great deal of pleasure."

Pius, in fact, had read Biondo, who was a frequent guide and companion on the pope's excursions about the Roman countryside (as he was for Colonna). And, although his books are "of considerable value though they should be read with caution, that you may not take the false for the true" (XI.42), Pius had consulted them in writing his own interpretation of the wrecks, and it is not surprising that the two accounts are so similar.

Almost a century later, in July 1535, there was a second attempt to raise the ship, this time using a primitive type of diving bell invented by maestro Guglielmo de Lorena (William of Lorraine—which suggests that he was French rather than Italian and so, Guillaume de Lorraine, as McManamon identifies him). The venture is described by Francesco de' Marchi in his treatise Della architettura militare (II.82–84), which was published posthumously in 1599 but more readily known from the 1810 edition by Luigi Marini.

Although sworn to secrecy about the mysterious contrivance, de' Marchi does reveal some details about the istrumento in his account of two exploits underwater (Guglielmo made the first dive himself). A hooped wooden cylinder, made waterproof by an application of pitch and tallow, was fitted over his head, resting on the shoulders and supported by a harness. It extended almost to the elbows, which permitted him to move his arms freely below the rim, cutting, sawing, tying, and hammering. There was another hoop of lead to provide ballast (and so compensate for buoyancy) and a small crystal viewing port. On the surface, a raft in which a hole had been cut in the middle allowed the crew to use a capstan and windlass to raise or lower the diving chamber (like drawing water from a well, as de' Marchi phrases it), being careful to keep it perfectly vertical so as not to tip over and allow water to enter. By tugging on a rope, he could signal to have the contraption raised or release himself from the harness and swim to the surface himself.

In spite of a ruptured eardrum experienced on his first dive by not having equalized the pressure inside his head (in a descent almost fourteen meters deep), de' Marchi relates how exhilarating it was to see and feel the Roman wreck beneath his feet. But he also ruefully comments on the small fish that appeared so much larger through the magnifying effect of the lens, nibbling first on the crumbs from the stale bread and cheese he had taken with him—and then on the nether parts of his naked body. Bleeding from his nose and mouth after the rupture of his eardrum, distracted by the incessant attention of the fish, and the numbing coldness of the water, de' Marchi had to abandon his search after only half an hour.

The second dive was more successful and lasted a full hour, after which he released himself from the harness and swam to the surface. The ruptured eardrum obviated the need to equalize pressure in his head and, this time, de' Marchi wore breeches. He was able to attach iron hooks to the wreck, allowing sections of pine, cypress, and larch to be pulled away and winched to the surface. Nails of copper and brass of varying sizes were recovered, the longest measuring two palms or almost a foot in length. Smaller tacks spaced less than three inches apart, "their shining heads...cut like stars," were used to secure the thin lead sheathing, the pattern on the underside designed to made for a stronger fit when driven in. Indeed, they still held sheets of tarred woolen cloth and lead that had protected the wood. Iron nails, almost completely deteriorated, were recovered, as well as red brick pavement tiles, slabs of what de' Marchi called red enamel, and fragments of opus sectile flooring. His most significant discovery, however, was that the planks of the hull were fitted edge to edge by mortise-and-tenon joinery and then secured by pegs—which were sawn off flush to the surface, a detail that he much admired.

The hull itself remained partially buried in the mud, and the efforts of sixteen additional men recruited from nearby Nemi were unable to lift it, the thick rope snapping in two. Everything else, enough material "to load two strong mules," was taken to Rome for study. But the recovered artifacts (even many of the nails) and notes on the project subsequently were lost to thieves who, he said, had hoped to discover something more about "this ingenious instrument of Master Guglielmo."

As promised, de' Marchi says nothing about the mechanism that allowed a diver to breathe in oxygen and flush exhaled carbon dioxide from the chamber—and maintain the water level inside. Given the technology of the time, there were only two options to do so: either by a connecting hose supplied with air by means of a bellows (it not being possible to draw breath through a tube much longer than half a meter at more than one atmosphere of pressure), or by using smaller casks of air sent down at regular intervals, which then were transferred to the chamber.

Reading in Marini that it "has no conduit for communication with the air outside the water" (e non ha alcun condotto di comunicazione coll' aria al di fuori dell' acqua, p. 366), Eliav, who translates the passage as "there was no tube or pipe for connection with the air out of the water," concluded that, in the absence of a hose extending to the surface, the second option must have been used. He suggests that inverted casks of air were lowered every few minutes, which then would be brought inside and, by releasing a plug, the fresh air allowed to escape. Stale air would be vented by a one-way pressure value at the top of the chamber.

If, in fact, this was how Guglielmo managed to convey fresh air from the surface, it anticipated by more than a century and a half the diving bell of Edmond Halley, who in 1691 used a constant series of empty weighted barrels to transfer air, compressed by water pressure as they descended, to the bell by means of an attached hose—so that, in Halley's own words, "Through these Hose, as soon as their ends came above the Surface of the Water in the Barrels, all the Air that was included in the upper parts of them was blown with great force into the Bell."

But Jung questions how practical it would be to follow a walking diver, always being directly above him on a taut line so as to continually lower tanks of air without tipping them and, in turn, how busy he would be in constantly refilling the chamber. Moreover, in returning to the original 1599 edition of de' Marchi, Jung discovered the reading to be that there simply was no spiracolo ("breathing hole") above the water—and so a connection for an air hose and bellows was not necessarily excluded and could have been used after all.

(The notion that air could be trapped in an inverted vessel when submerged was well known. Aristotle had conceived of a diver being able to breathe underwater by means of "letting down a cauldron; for this does not fill with water, but retains the air, for it is forced down straight into the water; since, if it inclines at all from an upright position, the water flows in," Problemata, XXXII.5. And Alexander the Great, curious to discover what lay at the bottom of the sea, was fancifully said to have constructed a glass bell within an iron cage "to attempt the impossible," Alexander Romance, II.38.)

There was not another attempt at recovery for almost three centuries, this time in September 1827 by Annesio Fusconi, a hydraulic engineer who later published an account of his exploit in a brief pamphlet, Memoria Archeologico-Idraulica sulla Nave dell' Imperator Tiberio. Thirty-thousand lire (about $103,000) was invested, much of it spent staging a mise en scène (including a viewing platform) for the diplomats and nobility invited to witness the spectacle. He also improved upon the diving bell developed by Halley, which now held eight men and used pumps ("a sucking and compressing machine") of his own invention to convey air from the surface by means of a leather hose. Materials were transported from Rome to Genzano and then laboriously down to the shore, where a large raft was constructed that supported three trestles spanning a central opening. Using a capstan, the principal one was used to raise and lower the bell, the other two to provide tools to work underwater and chests to contain whatever was salvaged.

Divers (marangoni, from the Latin mergus, "loon"), swimming to and from the bell, also wore waterproof clothing to protect against the cold. The intention was to take the first ship, the prima nave (the one nearer to shore) apart piecemeal, and beams of larch and pine, nails (some of copper with gilt heads), disks of porphyry and serpentine, enamels and mosaics, terracotta pipes, and bricks framed in iron with the inscription TIB.CAES were recovered, while other artifacts seen at the bottom of lake could not be raised. But the labor of acquiring antiquities in such a way soon proved too expensive, and the project was abandoned. Most of the recovered items were sold to the Roman nobles on shore or to collectors, others to the Vatican, which purchased (among other things) the disks and a beam studded with fourteen gilt-headed copper nails. Others were subsequently lost, even the diving apparatus, which was stolen by thieves when work had been suspended for the winter, early rains and falling temperatures having made the lake too cold for diving. The wine barrels that had supported the raft were taken as well—and no doubt put to better use on shore. Essentially a treasure hunter, Fusconi likely would have dismantled the wreck altogether had his depredations not been abbreviated.

But all this simply was a prelude to the sensational discoveries of October 1895. Having heard from local fishermen about a ship of Tiberius sunk in the lake and seeing one of its timbers at the palace of Prince Orsini, who now owned the land, the antiquities dealer Eliseo Borghi sought permission (under the supervision of the Ministry of Public Education, which dutifully issued a permit) to make a further examination of the wreck. Again, a diving platform was built and cranes assembled. By this time, the first closed diving helmet, fitted to a waterproof suit of rubberized canvas, had been invented and perfected by Augustus Siebe. Thus outfitted, a skilled diver was able to recover many of the bronze protomes that had decorated the prima nave.

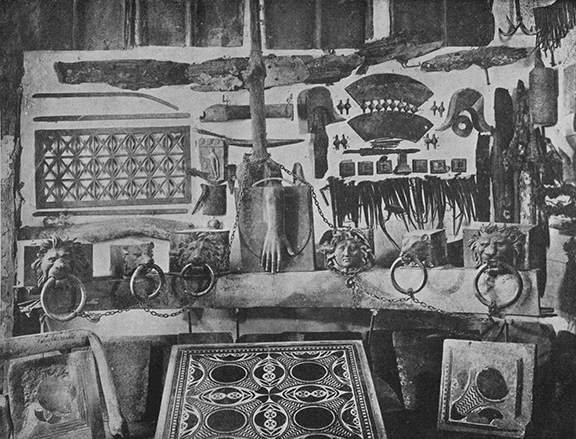

As Borghi relates in La Verità sulle Navi Romane del Lago di Nemi (1901), on "a day that should be remembered as an important date in the history of archaeological research," the first piece brought to the surface was a magnificent lion's head holding a mooring ring in its mouth that had capped one of the long steering rudders. A wolf's head was recovered, cast to be fitted to a square through-beam, and then two more lions and another wolf. There also was an exquisite bust of Medusa (top) and a square mosaic of opus sectile, as well as lengths of lead pipe, gilded bronze roof tiles, a large bronze grate, and ball bearings.

In November, a second ship was discovered, Borghi having been directed to its location in deeper water some four hundred meters south of the first one. Fragments of wood were recovered studded with nails and, most significantly, an artistic bronze panel depicting an extended hand and forearm.

=

=

Several lengths of lead pipe were stamped G. Caesaris avg germanic. They belonged, not to Tiberius or Trajan as previously thought, but to Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus—Caligula, the profligate emperor who had been assassinated by his own praetorian guard in AD 41. The two ships may have been deliberately scuttled by his successor Claudius (or even Nero) when the memory of Caligula was unofficially condemned (damnatio memoriae) (Dio, Roman History, LX.4.6; Suetonius, Life of Claudius, XI.3). Or they simply may have been abandoned to sink on their own or foundered in a sudden storm, which is suggested by the unexpected discovery of a small boat crushed beneath the ship. It even is possible that they were sunk to propitiate the goddess Diana, whose sanctuary was on shore. Pliny the Younger writes, for example, that on Lake Vadimo north of Rome "No boat is allowed on its surface—for it is sacred water" (Letters, VIII.20). So, presumably, would have been Lake Nemi.

These spectacular findings did not pass unnoticed. But, instead of being lauded for his discoveries, Borghi complained that "no enthusiasm, no loving solicitude, no encouragement came from the official element." Rather, the Ministry's representative on site notified the superintendent for antiquities and fine arts, who visited Nemi the next day and, hearing that crowbars were being considered to facilitate salvage, forbade their use. (In fact, two were later found.) When the second ship (seconda nave) was discovered, work was suspended altogether. Recovering the ships had become increasingly destructive, and such depredations were to cease until the operation could continue in a more scientific manner.

The Italian government adopted strict new regulations regarding its cultural patrimony, and a much aggrieved Borghi was obliged to sell his stored treasures. He was offered 128,000 lire, "but, as was to be expected, Parliament never voted on the necessary legislation to make that purchase definitive." Four years after Borghi's impassioned plea that the recovered artifacts were his personal property and a decade after they first had been discovered, a brief note appeared in a magazine on the arts: "The long conflict of Signor Eliseo Borghi with the Italian government, concerning the bronze objects he retrieved many years ago from Lake Nemi, has been settled by the payment to him of twenty-seven thousand dollars." And in 1906, they were indeed purchased for the National Roman Museum. (Although computing the historical value of money is notoriously difficult, when adjusted for inflation, the amount equates to approximately $900,000.)

Now under government supervision, a thorough underwater survey of the entire site was ordered by the Ministry of the Navy, which was conducted by Vittorio Malfatti, a naval engineer who wrote the official report of the exploration (Le Navi Romane del Lago di Nemi). Both ships had sunk in the northwest part of the lake. Delineating the outline of both with buoys, he found that the prima nave measured about sixty-four meters in length (actually it is about seventy three) with a beam of twenty meters and was twenty meters from shore, lying at a depth between five and twelve meters. The seconda nave was estimated to be seventy-one meters long and twenty-four meters wide. Two hundred meters from shore, it was half buried in the muddy bottom of the lake sixteen to twenty-five meters below the surface. If they were to be recovered at all, Malfatti contended, the lake itself would have to be drained, the level lowered by almost twenty-three meters. "This is evidently the most elegant solution, the one that appears to be the most convenient for the sure success of all the work."

This audacious proposal would not be realized for more than thirty years, when it was adopted by the fascist government of Benito Mussolini. He had become prime minister of Italy in October 1922 and was determined to reassert Rome's former grandeur—using archaeology to foster that ideology. Ruins were restored, especially Augustine monuments such as the Ara Pacis and Mausoleum. The imperial fora were excavated and showcased by a grand boulevard, the Via dei Fori Imperiali. Built in 1932, it ran in a straight line from Il Duce's residence at Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum, but cut soullessly through the archaeological park, entombing some of the unexcavated ruins beneath it. Recovering the two ships at the bottom of Lake Nemi would be a further demonstration of Italy's greatness, both past and present.

Late in the fourth-century BC, an emissary had been dug to regulate the water level of the lake, which otherwise threatened the Sanctuary of Diana. This ancient tunnel, cut from opposite ends of the crater, ran from the lakeshore below Genzano for more than a mile through the wall of the caldera to Lake Aricia on the other side, irrigating the surrounding valley. Strabo, in fact, speaks of the springs that fed the lake "but the outflows at the lake itself are not apparent, though they are pointed out to you at a distance outside the hollow, where they rise to the surface" (Geography, V.3.12). Once cleared of debris, water would be pumped through four large pipes into a receiving tank that, in turn, emptied into the emissary and then fed through a newly-cut channel across the now-dry lake bed and eventually to the Tyrrhenian Sea. Guido Ucelli, director of the company that manufactured the pumps, would direct the operation.

In October 1928, Mussolini himself (with Ucelli at his side) switched on the electric pumps that began to drain the lake. When the dropping water level damaged two of the pipes, a floating auxiliary station was established, with flexible piping connected to the pumps on shore. In March 1929, the stern of the prima nave appeared, revealing a sweep rudder nearly twelve meters long capped by a collar in the shape of a lion's head holding a ring in its mouth (like the one Borghi had discovered in 1895); then a wolf's head was revealed, also holding a ring, and another of a particolored panther.

The hull was found to have been filled with flat tiles set in mortar that overlaid the wooden decking and supported a pavement in polychrome marble and mosaics. Clay pipes, stacked and flanged so as to fit together in the space between one deck and another suggested that there was hypocast heating on board, as in a Roman bath.

More bronze bearings were recovered, two of which still were secured to a fragment of wood, their trunnions held in place by clamps. As later reconstructed, eight of these bearing balls were fitted to the underside of a platform, where they allowed it to rotate more smoothly. (Another table used wooden rollers.) Their exact purpose is not known but they may have been used for the revolving presentation of a statue, possibly of Diana. (Although these balls and rollers are not true ball bearings, in that they do not roll freely within a circular race, they served much the same function as the bearings first illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci almost fifteen-hundred years later.)

By September 1929, almost the entire hull of the prima nave had been exposed on the lakebed, and visitors were invited to inspect the site, making a circuit around the ship on a plank walkway. Artifacts were drawn to scale, photographed, and conserved. The hull itself was fitted to a large supporting cradle and in October 1930, two years after the ambitious project to recover the ships from Lake Nemi had been inaugurated, it began to be winched along a series of rails to temporary storage under a large wood-framed canvas hanger on shore.

In the meantime, work on draining the lake continued. By January 1930, the water level had been lowered by almost fourteen meters, revealing a portion of the seconda nave and, several weeks later, a section of deck railing crowned by double herms. But then a violent thunderstorm sank the auxiliary pumping station and work was suspended while it was salvaged. More powerful machinery was installed, and by June 1931 the second ship was completely exposed, only to be threatened by the shifting lake bottom and rising water, which again surrounded the hull. There was discussion that it be abandoned but, after seven months, the pumps were restarted and the ship again recovered from the mud. By October 1932 (the tenth anniversary of the Fascist march on Rome), the seconda nave had been hauled clear of the lake bed, but then began to warp and crack as the wood dried until it, too, could be preserved. Once sheltered, the same methods that preserved the Viking longships in Oslo were used to treat the wood, which was found to be local oak and fir, as well as pine and spruce—rather than larch or cedar, as originally thought.

By October 1935, the museum building was almost completed—except for its open front façade, which would allow the ships to be trundled into position: the prima nave the next month and the seconda nave two months later. There was a delay when the pavement of an ancient path that led from the Via Appia to the Sanctuary of Diana was discovered. Finally, on April 21, 1939 (the traditional day of Rome's founding), the Museo delle Navi Romane was opened to the public, the two great hulls so laboriously recovered displayed in their own gallery.

Five years later, both ships would be completely destroyed in a disastrous fire.

The liburnian originally was a small warship attributed to Illyrian pirates that had been employed by Octavian in the Battle of Actium (31 BC). Its most spectacular incarnation was the bejeweled vessel that conveyed Caligula along the coast of Campania from Rome to Naples—no doubt much like the barge on which Caesar and Cleopatra floated up the Nile (Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, LII.1). Still more massive ships were used to transport the obelisks of Egypt from Alexandria to Rome: "vessels which excited the greatest admiration....and looked upon as the most wonderful construction ever beheld upon the seas" (Pliny, XXXVI.xiv.69–70). The largest of these obelisks, which adorned the Circus Maximus, had been brought to Rome by Constantius II in "a ship of a size hitherto unknown...to be rowed by three hundred oarsmen" (Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman Antiquities, XVII.4.13).

But there also were ships of unimaginable splendor, such as the Syracusia of Hieron II, king of Syracuse (275–215 BC) and the thalamegos constructed by Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–204 BC). Given that the megalomaniacal Caligula may have been trying to emulate, if not surpass, them in grandeur, they suggest what the ships of Lake Nemi might have looked like.

The Syracusia is described by Athenaeus in the Deipnosophists (V.206e–209e). Shipwrights and artisans (some three hundred of them, not including their assistants) were assembled, as well as wood (sufficient for sixty quadriremes) and other building materials from Italy and Sicily, hemp from Iberia, and pitch from the Rhone. The ship was completed in just a year, its hull secured by bronze rivets, and "fixed to the timbers was a sheath of leaden tiles, under which were strips of linen canvas covered with pitch." There were three decks, the middle outfitted with passenger cabins.

"All these rooms had a tessellated flooring made of a variety of stones, in the pattern of which was wonderfully wrought the entire story of the Iliad; also in the furniture, the ceiling, and the doors all these themes were artfully represented. On the level of the uppermost gangway there were a gymnasium and promenades built on a scale proportionate to the size of the ship; in these were garden-beds of every sort, luxuriant with plants of marvellous growth, and watered by lead tiles hidden from sight; then there were bowers of white ivy and grape-vines, the roots of which got their nourishment in casks filled with earth, and receiving the same irrigation as the garden-beds. These bowers shaded the promenades. Built next to these was a shrine of Aphrodite large enough to contain three couches, with a floor made of agate and other stones, the most beautiful kinds found in the island; it had walls and ceiling of Cyprus-wood, and doors of ivory and fragrant cedar; it was also most lavishly furnished with paintings and statues and drinking-vessels of every shape. Adjoining the Aphrodite room was a library large enough for five couches, the walls and doors of which were made of boxwood; it contained a collection of books, and on the ceiling was a concave dial made in imitation of the sun-dial on Achradina. There was also a bathroom, of three-couch size, with three bronze tubs and a wash-stand of variegated Tauromenian marble, having a capacity of fifty gallons....Outside, a row of colossi, nine feet high, ran round the ship; these supported the upper weight and the triglyph, all standing at proper intervals apart. And the whole ship was adorned with appropriate paintings."

It was rivaled by the thalamegos of Ptolemy IV, which Athenaeus describes in even more detail (V.204d–206c).

"Philopator also constructed a river boat, the so‑called 'cabin-carrier,' having a length of three hundred feet, and a beam at the broadest part of forty-five feet. The height, including the pavilion when it was raised, was little short of sixty feet. Its shape was neither like that of the war galleys nor like that of the round-bottomed merchantmen, but had been altered somewhat in draught to suit its use on the river. For below the water-line it was flat and broad, but in its bulk it rose high in the air; and the top parts of its sides, especially near the bow, extended in a considerable overhang, with a backward curve very graceful in appearance. It had a double bow and a double stern which projected upward to a high point, because the waves in the river often rise very high. The hold amidships was constructed with saloons for dining-parties, with berths, and with all the other conveniences of living. Round the ship, on three sides, ran double promenades....As one first came on board at the stern, there was set a vestibule open in front, but having a row of columns on the sides; in the part which faced the bow was built a fore-gate, constructed of ivory and the most expensive wood....Connected with these entrances was the largest cabin; it had a single row of columns all round, and could hold twenty couches. The most of it was made of split cedar and Milesian cypress; the surrounding doors, numbering twenty, had panels of fragrant cedar nicely glued together, with ornamentation in ivory. The decorative studs covering their surface, and the handles as well, were made of red copper, which had been gilded in the fire. As for the columns, their shafts were of cypress-wood, while the capitals, of the Corinthian order, were entirely covered with ivory and gold. The whole entablature was in gold; over it was affixed a frieze with striking figures in ivory, more than a foot and a half tall, mediocre in workmanship, to be sure, but remarkable in their lavish display. Over the dining-saloon was a beautiful coffered ceiling of Cyprus wood; the ornamentations on it were sculptured, with a surface of gilt...Now the arrangements up to the first deck were as described. Ascending the companion-way, which adjoined the sleeping-apartment last mentioned, was another cabin large enough for five couches, having a ceiling with lozenge-shaped panels; near it was a rotunda-shaped shrine of Aphrodite, in which was a marble statue of the goddess. Opposite to this was a sumptuous dining-saloon surrounded by a row of columns, which were built of marble from India. Beside this dining-saloon were sleeping-rooms having arrangements which corresponded to those mentioned before. As one proceeded toward the bow he came upon a chamber devoted to Dionysus, large enough for thirteen couches, and surrounded by a row of columns; it had a cornice which was gilded as far as the architrave surrounding the room; the ceiling was appropriate to the spirit of the god. In this chamber, on the starboard side, a recess was built; externally, it showed a stone fabric artistically made of real jewels and gold; enshrined in it were portrait-statues of the royal family in Parian marble. Very delightful, too, was another dining-saloon built on the roof of the largest cabin in the manner of an awning; this had no roof, but curtain rods shaped like bows extended over it for a certain distance, and on these, when the ship was under way, purple curtains were spread out....the walls, too, they vary with alternating white and black courses of stone, but sometimes, also, they build them of the rock called alabaster. And there were many other rooms in the hollow of the ship's hold through its entire extent. Its mast had a height of one hundred and five feet, with a sail of fine linen reinforced by a purple topsail."

Julius Caesar had conceived of draining the Fucine Lake (Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, XLIV.3) east of Rome, but it was Claudius who actually made the attempt. An outlet three-and-a-half miles in length was cut, both by leveling and tunneling through a mountain, a project that took eleven years and the labor of thirty thousand men (Suetonius, Life of Claudius, XX.2; Tacitus, Annals, XII.56-57). Repaired during the reign of Hadrian (Historia Augusta, XX.12), the emissary again had became obstructed by the early third century AD, when Cassius Dio wrote that the money expended by Claudius had been in vain (Roman History, LX.11.5, LXI.33.5). The lake was not completely drained until the nineteenth century.

The head of Medusa (top), one of the most artistic of the bronze pieces recovered in 1895, is in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme (Rome), where it was photographed.

References: "The Mysterious Wreck of Nemi" (1896) by Rodolfo Lanciani, The North American Review, 162(471), 225-234; "Archaeological News: Italy: Nemi" (1896), American Journal of Archaeology, 11(3), 470-477; "The Roman Galleys of Lake Nemi" (1902) by H. Mereu, American Architect and Architecture, 77(1384), 11-13;"The Ships in Lake Nemi" (January 21, 1929) by John F. Gummere, The Classical Weekly, 22(13), 97-98; "The Ships of Nemi" (May 16, 2000) by Marco Bonino, a talk presented to the British Council in Rome; "Mysteries and Nemesis of the Nemi Ships" (1955) by G. B. Rubin de Cervin, Mariner's Mirror, 41, 38-42; "Notes on the Architecture of Some Roman Ships: Nemi and Fiumicino" (1989) by Marco Bonino, Tropis, 1, 37-53; Ancient Discoveries: The Revolutionary Work of Ancient Shipbuilders (2005), the History Channel; "Caligula's Floating Palaces" (2002) by Deborah N. Carlson, Archaeology, 55(3), 26; "The Liburnian: Some Observations and Insights" (1997) by Olaf Hockmann, The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 26(3), 192-216; "The Roman Villa by Lake Nemi: From Nature to Culture—Between Private and Public" (2005) by Pia Guldager Bilde, Roman Villas Around the Urbs: Interaction with Landscape and Environment edited by Barbro Santillo Frizell and Allan Klynne; Anchors: An Illustrated History (1999) by Betty Nelson Curryer; Caligula's Barges and the Renaissance Origins of Nautical Archaeology under Water (2016) by John M. McManamon (which concludes with de' Marchi); From Caligula to the Nazis: The Nemi Ships in Diana's Sanctuary (2023) by John M. McManamon (the most useful survey); L'incendio delle Navi di Nemi: Indagine su un cold case della Seconda guerra mondiale (2023) by Flavio Altamura and Stefano Paolucci—reviewed in "Nazis 'wrongly accused' of destroying Caligula's pleasure boats" (2023, April 25) by Tom Kington, The Times (London); "Guglielmo's Secret: The Enigma of the First Diving Bell Used in Underwater Archaeology" (2015) by Joseph Eliav, International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology, 85(1), 60-69; "A New Hypothesis on Francesco De Marchi (1504-1576) and His Dives in Lake Nemi in 1535" (2021) by Michael Jung, The International Journal of Diving History, 13, 225-33; History of Ball Bearings (1981) by Duncan Dowson and Bernard J. Hamrock (NASA Technical Memorandum 81689); "Bulletin and Record: Art News from the Old World" (1905, June), Brush and Pencil: An Illustrated Magazine of the Arts To-day, 15(6), 148.

Leon Battista Alberti: On the Art of Building in Ten Books (1988) translated by Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, and Robert Tavernor; Leon Battista Alberti: The Ten Books of Architecture (3rd ed.) (1755) translated by Giacomo Lenoi; The Works of Aristotle: Vol. VII, Problemata (1908) translated by E. S. Forster; Pseudo-Callisthenes: The Alexander Romance, translated by Ken Dowden (1989), in Collected Ancient Greek Novels edited by B. P. Reardon; Biondo Flavio: Italy Illuminated, Vol. I (2005) translated by Jeffrey A. White; The Commentaries of Pius II, Books X-XIII (1957) translated by Florence Alden Gragg, Smith College Studies in History, Vol. XLIII; Architettura Militare di Francesco de' Marchi, Vol. II (1810) by Luigi Marini; "The Art of Living Under Water: Or, a Discourse Concerning the Means of Furnishing Air at the Bottom of the Sea, in Any Ordinary Depths (1716) by Edmond Halley, Philosophical Transactions, 29(349), 492-499; Memoria Archeologico-Idraulica sulla Nave dell' Imperator Tiberio (1839) [by Annesio Fusconi]; La Verità sulle Navi Romane del Lago di Nemi (1901) by Eliseo Borghi; "Le Navi Romane del Lago di Nemi" (1896, June) by Vittorio Malfatti, Rivista Marittima, 29(6), 379-442; Le Navi di Nemi (1940, 2nd ed. 1950) by Guido Ucelli.

See also Cleopatra on the Cydnus.