Townley Discobolus

"Myron, who almost captured the souls of men and animals in his bronzes."

Petronius, Satyricon (LXXXVIII)

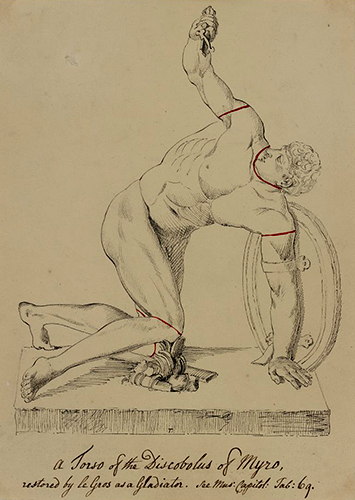

Although the athlete is in equilibrium, posed just before releasing the discus, the head of the Townley Discobolus is so passive in expression that it seems almost to be separate from the body—as indeed it is. The statue had been discovered at Hadrian's Villas in 1791 (another was found shortly afterwards) and purchased at auction by Thomas Jenkins, who had been born in Rome and served as the British banker there. He then sold the restored piece to Charles Townley for £400, assuring him that it was comparable to the famous copy owned by the Marchese Massimi that had been discovered ten years earlier. The head, however, was broken off, although Jenkins insisted that it belonged to the torso.

In the eighteenth-century, a connoisseur expected classical sculpture to be complete, as Gavin Hamilton, a more reputable dealer, once had acknowledged in a letter to Townley dated July 12, 1776, affirming that his client would not be content with any statue which is "not decided by its attributes & the head to be its own past a doubt." Now, nearly two decades later, Jenkins was writing on September 27, 1794 to insist that "The Head of Your Statue was not only found with it, but I believe You will See it is Precisely the Same Vein of Marble, that in Rome, there never was the slightest doubt of its authenticity."

That year, the statue itself arrived in London, prompting a worried Townley to question why the placement of the head did not accord with that of the Massimi Discobolus, in which the head looked away from the discus, rather than at it. Jenkins assured Townley that the head had been positioned correctly and that, having consulted the Papal antiquarian, his version actually was an improvement on Myron's pose! In fact, the antique head had not been oriented correctly, although it was the same type of marble and had been skillfully matched. Nor was it original to the statue.

"At that time of peace, the resort of noble and opulent Englishmen to Rome was particularly frequent; and a taste for the arts, promoted by a desire to embellish their own residences in England, was encouraged by competition of wealth. Occasions of gratifying these inclinations were not wanting, not only by the transfer of certain marbles from the known collections, to supply the occasional necessities of Roman Princes; but the sculptors intimately versed in all the arts of restoration, filled their exhibition-rooms with newly discovered fragments, so admirably re-adapted, as to present to unlearned eyes perfect statues of very exquisite workmanship....When this ardour of procuring fine statues was at its zenith, the Roman Virtuosi and Sculptors, from these causes, received ample encouragement, through the activity of their principal agent, Mr. Jenkins."

Nichols, Illustrations of the Literary History of the Eighteenth Century (Vol. III, p. 727)

The other discobolus discovered at Hadrian's Villa is behind the locked gate of the Sala della Biga in the Vatican Musems. Following the example of the Townley statue, its head also is positioned incorrectly. Jenkins enjoyed the confidence of Pope Clement XIV and sold Townley many of the pieces in his collection, beginning in 1768. But he was not above restoring a piece of sculpture, inflating its value, and passing it off as original—as in his dealings with another English collector, William Weddell, who purchased a Venus from him in 1765.

Nichols relates the story: The statue had been discovered by Gavin Hamilton, who had been commissioned by Lord Tavistock to collect such "statues or busts of merit and curiosity, for his intended gallery." But the Venus, "of such exquisite proportions and finishing as to rival the far-farmed statue De Medici," lacked a head. Jenkins, who had access to one in the Barberini Palace, offered to buy the piece, adding that "He did not understand the taste of English Virtuosi, who had no value for statues without heads; and that Lord Tavistock would not give him a guinea for the finest torso ever discovered." With the assistance of Bartolommeo Cavaceppi, one of the most skilled restorers of the time, who worked closely with Jenkins on such projects, a head of Agrippina was obtained. The veil that it wore was cut away, the whole piece reworked (with the addition of arms, part of a thigh and a leg) and "a perfect Venus arose." It then was sent to England, any objection by the Vatican having been "silenced by an offer" and every restoration exactly recounted to the custom house in order to reduce fees. Still, the statue was presented as "uninjured" and purchased by Weddell for the extraordinary sum (if Farington is to be believed) of £2000, plus a lifetime annuity for Jenkins of £100 per year—and this for a statue that Farington thought might be worth a tenth that.

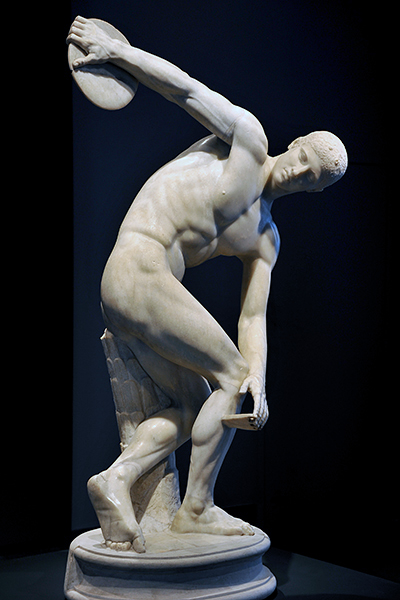

"'Do you mean the discus-thrower,' said I, "the one bent over in the position of the throw, with his head turned back toward the hand that holds the discus, with one leg slightly bent, looking as if he would spring up all at once with the cast?' 'Not that one,' said he, 'for that is one of Myron's works, the discus-thrower you speak of.'"

Lucian, Philopseudes ("The Lover of Lies") (XVIII)

Myron was renown in antiquity for a bronze heifer so realistic that it could have been mistaken for an actual cow, but it is the Discobolus ("Discus Thrower") for which he is most famous. The statue is a Roman copy of the mid-fifth century BC bronze and exemplified the Greek sense of harmony and balance so esteemed by Pliny.

"Myron is the first sculptor who appears to have enlarged the scope of realism, having more rhythms in his art than Polycleitus and being more careful in his proportions (symmetria). Yet he himself so far as surface configuration goes attained great finish, but he does not seem to have given expression to the feelings of the mind, and moreover he has not treated the hair and the pubes with any more accuracy than had been achieved by the rude work of olden days" (Natural History, XXXIV.xix.58).

Quintilian, who wrote in the first century AD, also mentions Myron's statue. In comparing the rhetorician and the artist, and the distinguishing personal style that makes each unique, he discusses the evolution of sculpture, which differs from that of Pliny. A stage of "softness" is attained by Myron, with a high point realized in the work of Polycleitus and Phidias, after which decline sets in.

"Some figures are represented as running or rushing forward, others sit or recline, some are nude, others clothed, while some again are half-dressed, half-naked. Where can we find a more violent and elaborate attitude than that of the Discobolus of Myron? Yet the critic who disapproved of the figure because it was not upright, would merely show his utter failure to understand the sculptor's art, in which the very novelty and difficulty of execution is what most deserves our praise" (Institutio Oratoria, II.13.10).