"It may not be unworthy of remark, that the only other piece of Sculpture which was ever removed from its place for the purpose of export was taken by Mr. Choiseul Gouffier, when he was Ambassador from France to the Porte; but whether he did it by express permission, or in some less ostensible way, no means of ascertaining are with the reach of your Committee. It was undoubtedly at various times an object with the French Government to obtain permission of some of these valuable remains, and it is probable, according to the testimony of Lord Aberdeen and others, that at no great distance of time they might have been removed by that government from their original site, if they had not been taken away, and secured for this country by Lord Elgin."

Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons (p. 7)

The French ambassador in Athens to the Ottoman court was the Count de Choiseul-Gouffier (1784–1792), who competed with Lord Elgin, his English counterpart, for access to the Parthenon marbles. French influence in Turkey then was at its height and, in 1788, Choiseul acquired two metopes, both of which had fallen from the temple—and, early the next year, a panel from the east frieze, which also was found in the rubble.

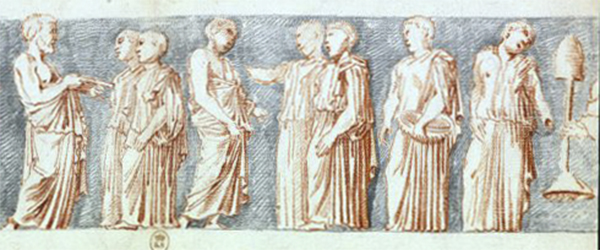

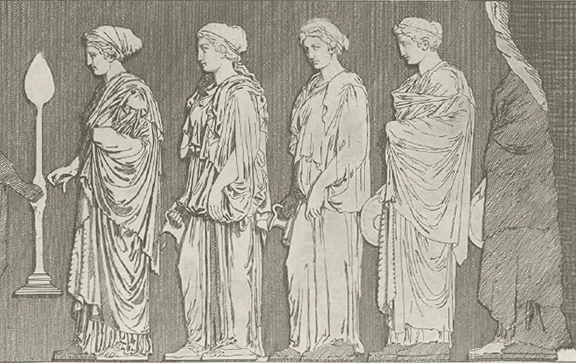

The frieze (Louvre, Ma 738) depicts a scene from the Great Panathenaia that was celebrated every four years to commemorate the birthday of Athena. Six Ergastinai ("weavers"), young noblewomen who were charged with weaving the sacred peplos that draped the olive-wood statue of the goddess, are shown solemnly approaching two priests, one offering (or receiving) a ritual item, the others waiting empty handed. Behind them, an Ergastine carries a phiale (Latin patera), a shallow bowl used for libations. Another turns to look at the procession behind her—or to help hold an incense burner, which is depicted on the other, broken half of the frieze.

These ceremonial vessels were used in offering dedications and sacrifices at the altar outside the Erechtheion, the Temple of Athena Polias named for the mythical king Erechtheus who had inaugurated the festival, and characterized by the six Caryatids that support its porch. (The suggestion that the Panathenaia is depicted first was proposed by Stewart and Revett in 1787. But so much of the ceremony is not represented that Connelly has argued that the frieze actually portrays the sacrifice of the daughters of Erechtheus.)

Choiseul's agent in Athens was Louis-François-Sébastien Fauvel, by profession a painter, who earlier had accompanied him on a tour of Greece and now served as his draftsman, drawing and taking casts—which are the earliest made of the monument, although Fauvel had no prior experience in molding. This watercolor by Fauvel depicts the east façade of the Parthenon (on the far side of the Propylaea, the ceremonial gateway to the Acropolis), where he had extricated the frieze (Block VII) from the rubble. It had been blown off in 1687, when a Venetian shell detonated the powder magazine stored there by the besieged Ottoman Turks, who assumed that the Christians would not attack the monument—in spite of having made it an irresistible target. (Just the year before, the Turks had demolished the Temple of Athena Nike to clear the way for an artillery placement. Gunpowder also had been stored in the Propylaea, which blew up when the building was struck by lightening in 1645.)

Fauvel had the frieze transported by twenty men and three pairs of oxen to the port at Piraeus, "where I had it sawn to half its thickness to make it more manageable" (Legrand, p. 31). In the process, however, the heads of three of the maidens, so beautifully preserved when the marble had been found, "were shattered by the clumsiness [les maladresses] of those who sawed it" (p. 237). Entrusted to the captain of the brig, they were shipped with the relief to Marseilles and then moved to Paris, where it arrived in 1789. In transit, the heads supposedly were lost, but Fauvel later wrote that only two of the figures had their heads when the frieze was found. The massive slab of marble, more than a foot thick, that had been sawn from the back of the frieze to reduce its weight and likely been intended to restore it later, was lost as well—stolen by the agents of Lord Elgin (p. 238).

Dutifully put in storage, the importance of the frieze as the only ex situ sculpture from the Parthenon (off site from the temple itself) was not fully appreciated. In 1801, it was transferred to the Louvre, where Bonaparte himself saw it early the next year, after inquiring whether the museum possessed any work by the Greek sculptor Phidias, who had supervised the construction and sculptural decoration of the Parthenon (Plutarch, Life of Pericles, XIII.4, 9). When told that it did, he expressed astonishment that the fragment had not yet been shown and insisted that the relief immediately be restored and put on display. That same year (1802), the Lourve was established as the Musée Napoléon, a name that would be retained until 1815, when the emperor abdicated after the Battle of Waterloo and again was sent into exile.

Choiseul's metope (the tenth from the south frieze, designated SM.10) depicts a scene from the battle between Centaurs and Lapiths (Centauromachy) at the wedding feast of the Lapith king Pirithous, a friend of Theseus, the founder of Athens and a guest at the celebration. Related to the Lapiths, the Centaurs came from Mount Pelion, which was the home, too, of Chiron, the oldest and wisest of them and tutor to such heroes as Achilles and Jason. Half beast and half man (and unused to wine), the Centaurs became drunk and tried to abduct Hippodamia, the bride. In the panel, one rears, clutching with his foreleg the thigh of a struggling Lapith woman as she grabs at his hands—and the peplos that is slipping from the shoulder, exposing her breasts.

With the abolition of the monarchy in 1792, Choiseul, a royalist, was forced to relinquish his post as ambassador. His marbles were confiscated by the Republic and, the next year, as revolutionary violence increased in France, he prudently emigrated to Russia, where he served at the court of Catherine the Great as director of the newly established imperial library. When Choiseul returned home a decade later, he managed to reclaim his metope but not the frieze.

Choiseul died in 1817. The next year, his heirs sold the metope to the Louvre (Ma 736) for 25,000 FF (a thousand guineas at the time), after a lively bidding war with the British Museum. Curiously, just two years later, the Louvre offered to exchange the metope for casts of the Elgin and other marbles in the British Museum. Although agreeing in principle, the Museum counter offered with casts to the value of £1,200—exactly what the Louvre had paid for the metope. Other than the frieze, the metope is the only other piece of sculpture from the Parthenon in its collection.

Late in 1788, the same year that Choiseul's metope had been shipped to France, he acquired a second one (SM.6) from Fauvel that had been dislodged during a storm and broken into three pieces. With the connivance of a Turk, it was said to have been thrown (or, more likely) lowered from the top of the citadel into a dung heap and secretly dragged away. But the metope remained in Athens, sequestrated there by the Ottomans when the French invaded Egypt—and watched over by Fauvel who, his payment in arrears, had stayed in Athens after Choiseul's departure, collecting and selling on his own. In 1803, at Bonaparte's command, it was shipped on the L'Arabe to Marseilles, one of twenty-six crates addressed by Choiseul to the Minister for Foreign Affairs—Talleyrand himself.

Just the week before, war again broke out between Britain and France, and the corvette carrying the metope was taken as a prize by the British. Sent from Malta to London on Lord Nelson's order, his expectation was that the booty would be purchased by the government. But it declined to buy the marble (or any of the other antiquities, as not being worth the duty fee). In consequence, everything languished in the custom house for three years until in 1806, still unclaimed, Elgin had some of the boxes purchased at auction for £24, thinking them to be his own.

He had just returned home that year, having been detained in France since 1803 as a foreign national in a time of war. Choiseul endeavored in vain to have him released and Elgin, in turn, had written to Nelson on his friend's behalf but, by then, the marbles already were in England and Nelson, too, could do nothing. Realizing that the broken metope belonged, in fact, to Choiseul, Elgin wrote to him, offering to return it. But Choiseul, under the misapprehension that the metope still was in Malta, did not respond. After Choiseul's death in 1817, the British Museum, which had purchased the Parthenon marbles only the year before (including the metope, 1816,0610.5), refused to recognize any further claim of ownership, regarding the matter as having been a personal one between Elgin and Choiseul.

In 1798, a decade after Choiseul had acquired his Parthenon marbles, Elgin was appointed British ambassador. Three months before, Nelson had been victorious at the Battle of the Nile, thwarting Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt, which then was part of the Ottoman empire. French influence correspondingly waned and that of the British increased as the Turks, solicitous that their nominal province be returned, sought to accommodate the victor. Late in 1799, a year almost to the day since his appointment, Elgin and his new bride (Mary Nisbet, a wealthy young heiress who brought to the marriage a dowry of £10,000) arrived in Constantinople.

When the French invaded Egypt, Fauvel was arrested and, in June 1801, transported to Constantinople. The next month, a firman (special letter of permission) from the Ottoman court arrived, ostensibly directing that Elgin not be hindered "from taking away any pieces of stone with inscriptions or figures." The original English memorandum making such a request had been granted in Turkish, which was officially translated into Italian (so as to be more readily accessible to the western reader), and then translated back into English for the Select Committee that later investigated the affair.

It was Elgin's understanding, as he later explained to the Committee, that this granted "me an authority to remove what I might discover, as well as draw and model" (p. 35). With the firman in hand and Fauvel no longer there to protest, the first metope was removed from the Parthenon just eight days later and, the next day, the one adjacent. Both were trundled to the port of Piraeus by a large cart and tackle that Fauvel himself had brought to Athens for the purpose but now, in his absence, were given over to Elgin. Transshipped via Malta and Alexandria, the pieces arrived in England in 1802.

Elgin also removed the badly damaged right-hand section of the east frieze (Block VIII; Smith, Catalogue 324) that had been built into the fortification of the Acropolis wall. It depicts a continuation of the Great Panathenaia procession. The foremost Ergastine holds a stand for burning incense, at the top of which a perforated cone allowed its scent to waft over the proceedings—and which is being reached for by her companion from Block VII. The other Ergastinai carry jugs and bowls for pouring libations. Originally, they all were part of a single slab which had broken in two, the break between occurring just in front of the incense stand.

Block VIII was part of seventeen cases transported to Piraeus, to which Elgin had dispatched his brig, the Mentor. Seven more crates remained behind, the hatches not wide enough to accommodate them. In 1802, the overloaded ship set sail for Malta but encountered a storm. In trying to make for safe harbor at the island of Kithyra, its anchors could not maintain a mooring and the foundering ship sank in about twelve fathoms of water. Over the next two summers, all the pieces were salvaged by Greek sponge divers (some hired from islands in the Aegean hundreds of kilometers away)—but then had to remain half-buried on the beach to protect them from pirates and the weather until they finally could be put in storage. Eventually, the shipment reached England—after Nelson's intervention and great expense to Elgin, who estimated the salvage to have cost him (rather, his wife) £5,000.

It was not until 1812—ten years after the Mentor first had set sail, that all of the Parthenon marbles acquired by Elgin finally arrived in England. In 1816, the frieze was purchased by the British Museum (accession number 1816,0610.24), when Elgin (then divorced and in debt) sold his collection for £35,000, less than half what he had spent acquiring it. A political cartoon sardonically observed at the time: "As the Turks gave them to our Ambassador in his Official capacity for little or nothing & solely out of compliment to the British Nation__I think he should not charge such an Enormous price for Packing & Carriage."

Benjamin Haydon, a staunch supporter of Elgin who spent hours at a time drawing the marbles (and even surreptitiously molded the best ones), bitterly remarked that Elgin might have gotten twice that amount from Napoleon but instead "was very badly treated, to gratify a malevolent coterie of classical despotic dilettanti devoid of all genuine taste or sound knowledge of Art" (p. 239). Indeed,

"His position was a delicate one. Suspended between the desire of saving from ruin and enriching his country with works which he felt were unequalled in beauty, and his dread of that which he knew would be immediately imputed to him, viz. having taken advantage of his public power and position to further private and pecuniary objects, he was tormented, as all men are tormented who, contemplating a service to their fellow creatures, feel the sad certainty that, for a time, they will stir up their hatred and provoke persecution instead of receiving legitimate gratitude and reward" (p. 206).

The French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1789–1815) only aggravated the rivalry between Britain and France in despoiling Greece of its national treasures. Ships were difficult to acquire and more dangerous to sail. The vagaries of war and the fortunes of one country or the other dictated, too, who was granted access to the Acropolis and its ruins. British debt after the war also affected Elgin's petition to the House of Commons. If money were to be spent, it was argued in parliamentary debate, better to alleviate the suffering of discharged sailors than be wasted on the acquisition of stones.

Although, as noblemen, Elgin and Choiseul behaved with courtesy to one another, their representatives did not. Fauvel's counterpart was the painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri, who supervised the architects and modelers sent to Athens and, after Elgin's arrest in 1803, was almost solely responsible for the collection and removal of antiquities to England. When Fauvel had been arrested, Lusieri schemed to take what he still possessed, including Choiseul's broken metope. Released three years later, Fauvel returned to Paris in 1801 and then in triumph to Athens in 1803 as French vice-consul—where he in turn conspired to seize what remained of Elgin's own collection. (Matters had reached such a point that in October 1805, by which time virtually all the sculptures had been removed, there was a complete ban on all digging, and further excavations were forbidden.)

Elgin's other principal agents were William Richard Hamilton (his private secretary, who had been on the Mentor when it sank and organized its salvage—and earlier had helped secure the Rosetta Stone for the British) and the Rev. Philip Hunt (Elgin's chaplain, who had obtained the firman). Writing in 1801, Hunt relates that he had heard that a metope (SM.6) "was taken down with so little skill, that the rope broke, and it was dashed into a thousand fragments." But this was hearsay; Hunt had not even arrived in Athens by then.

And it also was untrue. Fauvel relates that the metope already was broken into three pieces when it was found. But Hunt persisted in his misapprehension, confusing one metope with the other and conflating the two. In a long letter written in 1805 to the mother of Lady Elgin, he repeated the calumny: "M. de Choiseul-Gouffier's attempt to secure one had merely been connived at and for want of time and cordage and windlasses it fell from a considerable height and was broken into fragments" (XXI).

Even decades later, the Keeper of Antiquities of the British Museum felt compelled to remark that the frieze in the Louvre "has been unfortunately and unskilfully repaired, and modern heads are placed on the ancient shoulders; all these restorations have, in our cast, been sedulously removed, so that, as far as can be ascertained, nothing remains but what is original" (p. 65). And there still was the mistaken (and chauvinistic) insistence that the marbles had been detached from the Parthenon itself and that Choiseul had been the first to do so.

"The count himself removed the first sculpture from the Temple, and that it alone sustained any injury in the removal. The machinery he first used was defective, the ropes failed, and the marble was broken to pieces; fresh tackling was then procured from Toulon, and the removal proceeded successfully. The apparatus left behind by the Count was subsequently used by Lord Elgin, and no further damage in an instance occurred. It must not be forgotten, that the greater part of Lord Elgin's Collection was not taken from its original position on the building, but from among the ruins which had accumulated around it, and from the walls of the fortifications, into which many very beautiful pieces had been built" (Description of the Collection of Ancient Marbles in The British Museum, Pt. VIII, 1839, p. 98).

The earliest illustration of the frieze to show its heads had been published a dozen years earlier, in a catalog for the museum by Charles Clarac (Musée de Sculpture Antique et Moderne). A later edition (printed in 1841, two years after the complaint in the British Museum catalog) does note that the heads had been restored.

The comment by the British Museum seems petty indeed—and all the more so, given the statement that Elgin's own marbles had not been taken from the Parthenon "and no further damage in an instance occurred."

Two English travelers had been present in 1801, when Elgin's first two metopes were removed. One remarked that he had seen "several metopes at the south east extremity of the temple taken down. They were fixed in between the triglyphs as in a groove; and in order to lift them up, it was necessary to throw to the ground the magnificent cornice by which they were covered." Another lamented that, in endeavoring to lower one of the metopes,

"a part of the adjoining masonry was loosened by the machinery; and down came the fine masses of Pentelican marble, scattering their white fragments with thundering noise among the ruins....Looking up we saw with regret the gap that had been made: which all the ambassadors of the earth, with all the sovereigns they represent aided by every resource that wealth and talent can now bestow, will never again repair."

In removing another of the metopes, Lusieri confessed in a letter to Elgin in 1802 that "the piece has caused much trouble in all respects and I have even been obliged to be a little barbarous." An English traveler later witnessed such efforts. "The men were labouring long ineffectually with iron crows to move the stones of these firm-built walls. Each stone as it fell shook the ground with its ponderous weight with a deep hollow noise; it seemed like a convulsive groan of the injured spirit of the Temple."

"What! shall it e'er be said by British tongue,

Albion was happy in Athena's tears?

Though in thy name the slaves her bosom wrung,

Tell not the deed to blushing Europe's ears;

The ocean queen, the free Britannia, bears

The last poor plunder from a bleeding land:

Yes, she, whose gen'rous aid her name endears,

Tore down those remnants with a harpy's hand,

Which envious Eld [former ages] forbore, and tyrants left to stand."Lord Byron, Child Harold's Pilgrimage (Canto II, xiii)

Exposure to the open air has discolored the frieze in the Louvre. Its original gray-white surface, the brightly painted colors long faded, has acquired a variegated patina of brown and orange, likely the result of iron and other ferrous minerals in the marble reacting with rain water and moisture. The resulting honey-colored cast, most notably in the crevices and grooves of the sculptures, has tended to enhance the contrast with the polished surfaces, effectively taking the place of the original paint. This weathered effect was especially pleasing to the aesthetic sensibility of the nineteenth-century romantic, even more so when the remnants of a ruined civilization could be portrayed in the golden tint of sunset, as in Church's painting of the Parthenon (above).

Such discoloration is much less evident, however, in the Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum. The gallery where they were to be exhibited had been funded by Sir Joseph Duveen, a wealthy but disreputable art dealer who insisted that the stone be made as white as possible to satisfy a public expectation that this was the proper color of ancient marble. As a result, over a period of about eighteen months in 1937–1938 virtually all of the sculptures were aggressively cleaned (some with copper implements and carborundum) in preparation for the opening of the new hall. The result, St. Clair contends, was that the patina (and its original traces of paint and tool marks) was scraped and scoured away, rendering the marble a dull white. Jenkins argues that this is an exaggeration, although he does admit that weathered surfaces were rubbed smooth by the cleaning. (The damaged section of the procession that had been lost at sea was not cleaned, perhaps because of its vicissitudes, and the delicate lines left by the tools of the sculptor still can be seen.)

The unprecedented access of Duveen's workmen to the Parthenon sculptures, their unauthorized use of harsh abrasives, and the seeming attempt by the Museum to keep these facts from the public caused a scandal at the time, which largely was forgotten with the outbreak of World War II in 1939, when the Duveen Gallery was to be inaugurated. Damaged during the war, the gallery would not open to the public until 1962. The scandal itself was revisited by St. Clair in 1998, prompting the British Museum to host an international colloquium the next year to re-examine the issue.

At least the marbles were not restored, as was customary at the time. Certainly, that was Elgin's intention, who offered the work to Antonio Canova, the greatest sculptor in Europe. But Canova refused, Elgin quoting him as saying "It would be sacrilege in him, or any man, to presume to touch them with a chisel" (Memorandum, p. 40). If Elgin insisted, however, Canova would recommend his own pupil, John Flaxman, the leading neoclassical sculptor in England. But Flaxman demurred as well, saying, as Hunt wrote to Elgin, that "it would be a most difficult and laborious Undertaking.... That when done the execution must be far inferior to the original parts." More to the point, given Elgin's debts in 1807, the work would lower rather than increase the value of his collection—and cost more than £20,000.

Lord Byron, who died in Greece fighting for its independence, despised Elgin for his desecration of the Parthenon—and, as a Scot, for dishonoring his homeland. Byron's mother had been born there (and, like Elgin's first wife, also had been married for her fortune). In The Curse of Minerva (1811), written the year before Child Harold's Pilgrimage was published, Byron was even more damning. While sitting alone in the ruined Parthenon, the poet imagines himself suddenly confronted by Minerva (Pallas Athena), who says of Elgin—

"Yet still the Gods are just, and crimes are crossed:

See here what Elgin won, and what he lost!....

Some retribution still might Pallas claim,

When Venus half avenged Minerva's shame."

The reference is to the cuckolded Elgin's scandalous divorce in 1808—and his disfigured nose. Accounts vary as to the cause. The court transcript of the divorce trial records that Hamilton stated "while in Constantinople, his Lordship contracted a severe ague [malaria], which consequently resulted in the loss of his nose." He also agreed to the question put to him that "her Ladyship's interest in Lord Elgin began to wane at this point" and that the disaffection was due to the degenerative infection. Lady Elgin herself wrote that "The strange illness that has devoured most of Elgin's nose shows no sign of abating. I have the darkest fear that it is leprosy."

In fact, there was a suspicion that it was syphilis, which Elgin treated with large doses of mercury. (Byron also may have quipped "Noseless himself, he brings here noseless blocks / To show what time has wrought and what the pox.") Mary Nisbet's biographer is more circumspect, suggesting that the mercury had been used to treat her husband's asthma and that the divorce was due, not to Lady Elgin's adultery or her husband's disfigurement, but to her fear of another pregnancy—having had five children in less than six years, the fourth dying while she was pregnant with her fifth, the birth of which itself was traumatic. Refusing to sleep with him, she pleaded that "I am worn out and would rather shut myself up in a nunnery for life."

In the Doric Order, the entablature of a temple is comprised of the cornice, which is situated just below the pediment or gable of the roof and the architrave, which rests directly on the columns. Situated between these two elements is the frieze, which alternates between triglyphs (blocks of three vertical channels representing the ends of wooden ceiling beams) and, in the spaces between them, metopes (hence their name, "between the opening").

Sculpted in high relief from local Pentelic marble, the best preserved of these metopes, fifteen of which were appropriated by Elgin, ran along the south side of the Parthenon (originally, there had been ninety-two: thirty-two along each long side and fourteen at each end). Those on the other three sides were damaged in the devastating explosion of 1687.

When the Parthenon was converted to a church (possibly under Justinian in the sixth century AD), the south metopes were defaced by iconoclastic Christians determined to remove any pagan vestiges from the temple. (Cook, in the official British Museum guide, places the conversion in the early fifth century, when an apse and bell tower were added, and windows cut into the frieze.)

But some of these metopes were spared, possibly due to the perception of the Centaur in Christian iconography. In the Life of Saint Paul the First Hermit (c. AD 375), for example, Jerome relates that Antony, while searching for Paul in the desert became lost and prayed to God to show him "the fellow-servant whom He promised me." He was sent a Centaur who, extending his hand, pointed the way (VII). Antony then met a Satyr, who offered him food, confessing that he was there to represent the other inhabitants of the desert, piteously exclaiming "We pray you in our behalf to entreat the favour of your Lord and ours, who, we have learnt, came once to save the world" (VIII). Weeping, Antony berated the Alexandrians for worshipping monsters when monsters themselves spoke of Christ (cf. Isaiah 34:14, "The wild beasts of the desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow.")

This is a plaster cast of Block VII in the Sculpture Court of The College of Art, University of Edinburgh. Acquired in the 1830s, it shows how the frieze might have looked originally, after reconstructed plaster heads were added and the ECA cast then made.

During two weeks in 1674, thirteen years before the disastrous explosion that so damaged the Parthenon, a hurried set of red and black chalk drawings attributed to Jacques Carrey were made of the pediments, metopes, and frieze, some the sole record of their original appearance. They are all the more remarkable in that the frieze, which ran as a continuous tableau around the exterior of the naos or inner sanctuary, was observed from ground level forty feet below without the benefit of scaffolding or additional lighting.

In 1751–1753, thirty years before Choiseul arrived as ambassador, two English architects, James Stewart and Nicholas Revett, had visited Athens, intent on surveying its principal monuments. This engraving is from the second volume of The Antiquities of Athens (Plate XXII), which was published in 1757. It shows how Block VIII looked when they were there—and the terrible damage the frieze had suffered by the time it was recovered by Elgin.

There is no engraving of Block VII because it had been blown from the frieze by the exploding Venetian shell more than sixty years before and buried in the rubble. Fauvel, in fact, complains of this "immense debris" and that "it was only with great difficulty and after having broken 2 cables [and with the help of seven or eight men] that I was able to get it out of the hole where it was."

This sketch by Carrey shows how Choiseul's second metope, the one confiscated by the British, looked originally. Again, it shows the poignant loss suffered over a century and more of neglect and wanton destruction.

The painting of the Parthenon by Frederic Edwin Church (1871) is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York).

References: Lord Elgin and the Marbles (1998) by William St. Clair (the 3rd ed., which published for the first time the complete firman in Italian and the extent of the damage to the Parthenon marbles in 1937–1938); "Lord Elgin and His Collection" (1916) by Philip Hunt and A. H. Smith, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 36, 163-372 (an important paper written on the centenary of Elgin's sale to the British Museum); A Guide to the Sculptures of the Parthenon, in the British Museum (1908) by A. H. Smith (based on Smith's A Catalogue of Sculpture in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, British Museum (Vol. I) (1892); Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Earl of Elgin's Collection of Sculptured Marbles (1816); Memorandum on the Subject of The Earl of Elgin's Pursuits in Greece (1811) (Anonymous, although by Elgin based on Hunt's long letter to him in 1805); Cleaning and Controversy: The Parthenon Sculptures 1811-1939 (British Museum Occasional Paper, No. 146) (2001) by Ian Jenkins (also The 1930's Cleaning of the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum on the British Museum website); The Elgin Marbles (1984) by B. F. Cook ; "Les Fragments du Parthénon conservés au Musée du Louvre" (1894, January) by Étienne Michon, Revue Archéologique (Series III), XXIV, 76-94; corrected in subsequent issues by Philippe-Ernest Legrand in "L'Histoire des Marbres du Parthhénon" (1894, July), XXV, pp. 28-33 and "Encore les Marbres du Parthénon" (1895, January), XXVI, pp. 237-239; The Parthenon (2002) by Mary Beard (a popular account); "Losing the Heid... or not" (October 10, 2019) by Norman Rodger, The University of Edinburgh, Library & University Collections (blog); "The Days of Duveen" by S. N. Behrman, The New Yorker (the first of a series of long articles that ran from September 22–October 26, 1951); "Lord Elgin's Collection of Grecian Antiques" (1803, August 16), The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, LXXIII, Pt. II, 725-726; also LXXX, Pt. II (1810, September 13), 333- 334; The Letters of Mary Nisbet of Dirleton Countess of Elgin (1926) edited by Nisbet Hamilton Grant; "Descensus ad Terram": The Acquisition and Reception of the Elgin Marbles (1967) by Jacob Rothenberg (PhD dissertation); The Parthenon Frieze (1994) by Ian Jenkins; "Gaspari au Ministre" (letter dated February 27, 1788) (1884) Bulletin de la Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France, p. 57 (Gaspari then was French vice-consul in Athens); The Elgin Affair (1997) by Theodore Vrettos; Mistress of the Elgin Marbles: A Biography of Mary Nisbet, Countess of Elgin (2004) by Susan Nagel; "Acquisition and Supply of Casts of the Parthenon Sculptures by the British Museum, 1835–1939" (1990) by Ian Jenkins, The Annals of the British School at Athens, 85, 89-114; The Trial of R. Fergusson, Esq. for Crim. Con. with the Rt. Hon. Lady Elgin... (1807); "Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze" (1996) by Joan B. Connelly, American Journal of Archaeology, 100(1), 53-80; The Autobiography and Memoirs of Benjamin Robert Haydon (1926) edited Aldous Huxley. The classic nineteenth-century study is Der Parthenon (1871) by Adolf Michaelis, who originally numbered the panels. Many of the primary sources, such as Revue Archéologique (online at Gallica) and the work of Alessia Zambon, are in French—or in Greek, e.g., "ΠΈΡΙ ΤΏΝ ΕΛΓΙΝΕΙΩΝ ΜΑΡΜΑΡΩΝ [About the Elgin Marbles]" (1888) by Antonios Myliarakis, Hestia, XXXVI, 681-799 (which records the deposition of the Mentor's captain).

See also Erechtheion, Museum of the Imperial Forums, and Stewart and Revett.