Behind the scaena of the theater dedicated by Pompey the Great in 52 BC, there was a portico "to which, in the case of sudden showers, the people may retreat from the theatre, and also sufficiently capacious for the rehearsals of the chorus" (Vitruvius, On Architecture, V.9.1). The porticus Pompeianae also was a favorite promenade, where one could stroll among its shady gardens and fountains, rows of plane trees, works of art (Pliny, Natural History, XXXV.lix.126, 132)—and colonnades hung with a canopy of woven gold cloth called Attalica aulaea, after Attalus, the King of Pergamum, who was said to have invented it (Valerius Maximus, Memorial Doings and Sayings, IX.1.5; Ovid, Art of Love, III.387; Propertius, Elegies, II.32.11–12). The venerable portico still was esteemed in the time of Martial (Epigrams, V.10) and seems to have attracted an idle crowd almost from the beginning. A character in Catullus, looking for a friend, meets "the worst of girls" to ask after him. Baring her breasts, she replied "'Look, here he is, hiding between my pink tits'" (Poems, LV.11–12; Martial, XI.1; Propertius, IV.8.75). Certainly, it was a favorite place to meet women (Martial, XI.47; Ovid, I.67; Propertius, II.32.11-12).

"the portico of a hundred hanging columns"

Martial, Epigrams (II.14)

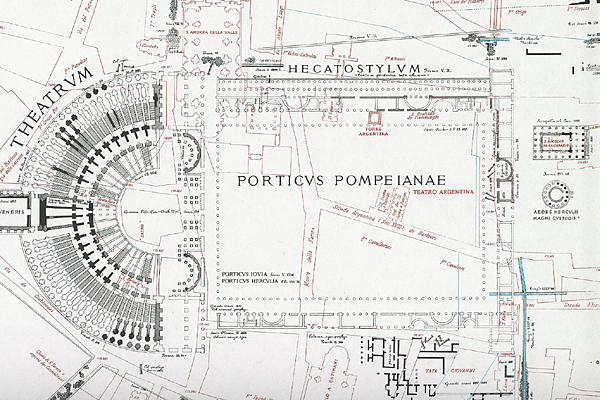

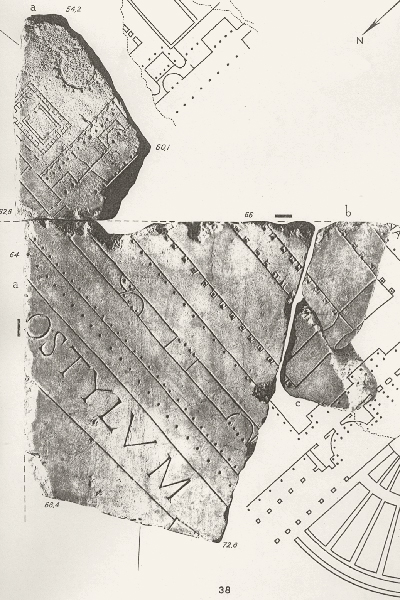

As can be seen in this detail from the Forma Urbis Romae, the piazza is surrounded by a single colonnade with exedras, both semicircular and rectangular, along the far sides and the back. The four files of dotted squares in the open area may be the rows of plane trees mentioned by Propertius. They are next to long rectangles that may represent basins of water.

At the top (the eastern end of the portico) is an exedra where Julius Caesar was assassinated. It is this place, the Curia of Pompey, "which was the scene of that struggle and murder, and in which the senate was then assembled" (Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, LXXX.4; Plutarch, Life of Julius Caesar, LXVI.1–2, Life of Brutus, XIV.1–2; Dio, Roman History, XLIV.16.1–2). So enraged were the people that the chamber was set afire (Appian, Civil Wars, II.147) but not before the statue of Pompey, at the foot of which Caesar was slain, was removed (Suetonius, Life of Augustus, XXXI.5). The hall subsequently was walled up (Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, LXXXVIII) and the site later converted to a latrine (Dio, XLVII.19.1).

Martial is the first to mention the portico known as the Hecatostylum, which is so prominently incised on the Forma Urbis, and its one-hundred columns. He mentions it one other time to say that bronze figures of wild animals were displayed there amid a grove of plane trees (III.19.1-2). There also were plane trees in the portico of Pompey, but Martial implies that the two places were separate, the character in the poem first visiting the hundred columns "and from there to the gifts and double groves of Pompey" (II.14.10). If not a distinct site, the columns may be part of the Baths of Agrippa.

As can be seen, the Hecatostylum lies on the northern side of the Porticus Pompeii and seems to have been a double colonnade, the two rows separated by a raised step. The columns in the middle of the outer aisle supported a roof with more numerous columns facing the inner aisle. Two large exedras can be seen in the wall screened by more columns.

The eastern end of the portico abuts four Republican temples, two of which can be seen above in a detail from the topographical atlas of Rodolfo Lanciani (1901) and incised on a fragment of the Forma Urbis Romae. One is thought to be the Temple of Juturna and, next to it, a round temple, which is shown above. This is as close as the public can hope to be to the site of Caesar's assassination.

Reference: La Pianta Marmorea di Roma Antica: Forma Urbis Romae (1960) by Gianfilippo Carettoni, Antonio M. Colini, Lucos Cozza, and Guglielmo Gatti.