It was at the first celebration of the Consualia in honor of Consus, an ancient god of the granary or storehouse, that the rape of the Sabine women was thought to have occurred. Romulus is said to have held chariot races which were so distracting, says Livy, that "nobody had eyes or thoughts for anything else" (History of Rome, I.9) While the men watched the races, their unmarried women were abducted by the Romans to be their wives.

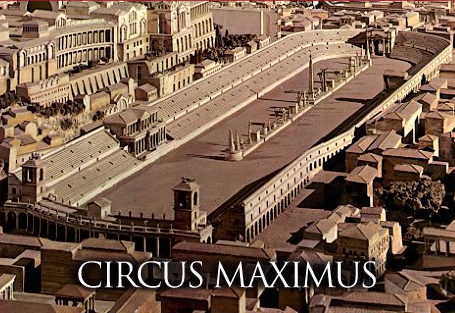

The races took place on either side of a brook that ran between the Aventine and Palatine hills, and it was in the middle of this valley that the Circus Maximus traditionally was thought to have been founded in the sixth century BC by Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth king of Rome (Livy, I.35). By channeling and bridging the stream, an euripus (a water-filled channel) was created that served as a barrier or spine (spina) for the track. Livy records that in 329 BC permanent starting gates were constructed (VIII.20) and, in 174 BC, that they were rebuilt and seven large wooden eggs set up between columns on the spina to indicate the completion of each lap (XLI.27). Livy also speaks of turning posts, which must have been restored rather than built for the first time. In 46 BC, Julius Caesar lengthened the track and built an euripus around it (Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, XXXIX.2). In 33 BC, Agrippa supplemented the eggs with seven bronze dolphins, and had another set of eggs placed near the starting gates to mark laps for the charioteers (Dio, History of Rome, XLIX.43.2). After a fire destroyed much of the Circus in 31 BC (L.10.3), Augustus constructed the pulvinar, a shrine built into the seating below the Palatine Hill, which was used as an imperial box to watch the games and where images of the gods were installed after having been brought in procession from the Capitol (Res Gestae, XIX). In 10 BC, he also erected an obelisk on the spina as a dedication to the Sun and a monument of his conquest of Egypt.

This is the Circus that so impressed Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who described it in 7 BC as "one of the most beautiful and admirable structures in Rome" (Roman Antiquities, III.68), measuring three and a half stades in length and four plethra in width (2,100 by 400 Greek feet, slightly more than the English equivalent), and seating 150,000. Surrounding the track was the euripus, ten feet wide and ten feet deep, to protect spectators from the wild animals that were exhibited there before the construction of the Colosseum. Outside, says Dionysius, "there are entrances and ascents for the spectators at every shop, so that the countless thousands of people may enter and depart without inconvenience." Inhabited by cooks, astrologers, and prostitutes, it was in this arcade of wooden shops that the disastrous fire of AD 64 broke out during the reign of Nero (Tacitus, Annals, XV). Pliny the Elder considered the Circus to be one of the great buildings in the world, able to seat 250,000 persons (Natural History, XXXVI.xxiv.102), a figure that must have included those who were able to view the arena from the slopes of the Aventine and Palatine hills.

By AD 103, after another fire (possibly the one of AD 80), Trajan restored the Circus to its greatest splendor, rivaling the beauty of temples says Pliny the Younger. Three stories high, with arches and engaged columns in the first story, the seating areas were divided into zones by walkways. The seats in the first tier were of marble and, aside from those in the front row, along a portion of the podium wall reserved for senators (Suetonius, Claudius, XXI.3), and other seats for the equites who sat behind them (Tacitus, Annals, XV), were not segregated as they were in the Colosseum and the theater. Men and women could sit together, an opportunity for flirtation and dalliance of which Ovid was not unaware.

Although the Circus Maximus was designed for chariot racing (ludi circenses), other events were held there, including gladiatorial combats (ludi gladiatorii) and wild animal hunts (venationes), athletic events and processions. By the time of Augustus, seventy-seven days were given over to public games during the year, and races were run on seventeen of them. There usually were ten or twelve races a day, until Caligula doubled that number and, from the end of his reign, twenty-four races became typical (Dio, LX.23.5; 27.2). (The number of festivals in which racing occurred also increased, with Circus games instituted in honor of Caligula's mother and sister, and Tiberius.) Still, Domitian once had one hundred races a day but reduced the number of laps to five to fit them all in (Suetonius, IV.3), and Commodus ran thirty races run in just two hours one afternoon in AD 192 (Dio, LXXIII.16.1). These numbers are exceptional and not likely to have been repeated, if only because the horses had to be transported from the Campus Martius, where they were stabled, over a mile away.

The chariots started from twelve gates (carceres), six on either side of an entrance that led from the Forum Boarium. Above sat the presiding magistrate at whose signal the races began. Far at the other end, along the sweeping curve (sphendone) of the track, was another gate by which processions entered the Circus. In AD 80, it was rebuilt as a triumphal arch to commemorate the conquest of Judea by Titus. On the spina, itself, were various monuments and shrines, including one to Consus and another to Murcia, who may have been the divinity of the brook over which the Circus was built. At either end were the metae or turning posts, comprised of three large gilded bronze cones grouped on a high semicircular base. There were thirteen turns, run counter-clockwise, around the metae for a total of seven laps (spatia), a distance just over three miles (approximately twice that of a modern track), depending upon how close to the inside the driver could stay. It could have been run in eight to nine minutes, just about the length of the race in the movie Ben Hur.

To ensure a fair start, the starting gates were built along a slight curve so that the distance to the break line, before which the chariots were not allowed to leave their lanes, was the same for each. Drivers were required to stay within a marked lane until that point was reached, after which they could jockey for position. Lots were drawn to determine which gate was selected, and it was from the gates that the race actually began. The presiding magistrate (either a praetor or consul) dropped a white starting flag (mappa), the gates to the stalls flew open, and the race began.

The quadriga was pulled by four horses, two outside horses, which were not yoked but harnessed only by a rein or trace, and a yoked pair in the center, the right horse of which was considered to be the more important. The inside trace horse (funalis) also had to be the strong to set the pace and take the turns around the metae and, of the horses in the team, likely was the one named in inscriptions. The number of sharp turns and the hard surface of the track (even though there was a covering layer of sand) meant that it was the one which was most at risk for concussions and strains or even broken bones, given its position between the spina or metae and the yoke horses. There were other dangers, as well, which Pelagonius, a fourth-century practitioner, enumerates in his Ars Veterinaria. They included blows to the eyes from an opponent's whip (XXX.410-413) or a cut tongue from a bit pulled too hard (V.66), as well as injuries from being hit by a chariot wheel or axle (XV.233, XVI.252). The horse's tail also could tangle in the reins, and usually was bound or even cut (XXI.292).

Race horses were carefully bred and their conformation and pedigree a matter of importance. They did not begin racing until they were five years old (although Columella says that three-year olds could begin training but should have a year's training before competing, VI.29.4) and often had long careers afterwards. The best horses came from stud farms in North Africa and Hispania, and were transported to Rome on special ships (hippago) designed for the purpose. Most often, those that competed in the Circus were stallions, which also were in demand for breeding.

If the horses were well bred, the charioteers (aurigae) who drove them were not. Most were slaves or freedmen and, like the gladiator, were infamis and of low social status. Competitors often would turn in front of one another, hoping to force a collision and cause their opponent to wreck (naufragium). To gain leverage, the charioteer wrapped the reins around his waist, bracing the body and steering by shifting his weight. In the event of a crash, he could extricate himself only by cutting the reins with a curved knife, which was carried in the straps of his torso lacing. Since fouls often were deliberate, the risk of being dragged or caught under a wheel was very real. There were times, too, when, as Martial (VI.46) hints, it might be prudent to hold back and not disappoint the expectations of the emperor. Too egregious a situation, however, and there would be an outcry from the spectators, who, as Ovid indicates, would wave their togas and insist that the race be stopped and run again. Cassius Dio (LX.6.4-5) records that the number of races that had to be restarted eventually became so excessive, some races being rerun as many as ten times, that Claudius severely limited their number.

The best charioteers were both lionized by the public and cursed as witches or magicians (how else to explain their repeated victories). During the reign of Valentinian (AD 364-375), Ammianus Marcellinus records several instances of prosecution for witchcraft. One charioteer was condemned for having his own son trained in the black arts to better help his father (XXVI.3); another popular charioteer was accused of practicing sorcery and burnt at the stake, even though he "had given such general pleasure" (XXIX.3). Lead "curse tablets" also invoked the most terrible fate for rival factions.

"I adjure you, demon whoever you are, and I demand of you from this hour, from this day, from this moment, that you torture and kill the horses of the Greens and Whites and that you kill in a crash their drivers...and leave not a breath in their bodies."

"I conjure you up, holy beings and holy names, join in aiding this spell, and bind, enchant, thwart, strike, overturn, conspire against, destroy, kill, break Eucherius, the charioteer, and all his horses tomorrow in the circus at Rome. May he not leave the barriers well; may he not be quick in contest; may he not outstrip anyone; may he not make the turns well; may he not win any prizes..."

"Bind every limb, every sinew, the shoulders, the ankles and the elbows of...the charioteers of the Reds. Torment their minds, their intelligence and their senses so that they may not know what they are doing, and knock out their eyes so that they may not see where they are going—neither they nor the horses they are going to drive."

Charioteers could win fabulous wealth, at least those who were freedmen, who always could threaten to drive for another faction. Prize money ranged from fifteen to thirty thousand sesterces to as much as sixty thousand for a single victory. Juvenal complains that a chariot driver could earn a hundred times the fee of a lawyer (VII.114), and Martial writes of Scorpus winning fifteen bags of gold in an hour. Diocles, a charioteer from Lusitania who competed during the reign of Hadrian and Antoninus Pius, won prize money totaling 35,863,120 sesterces before retiring at age forty-two. An inscription dedicated in his name records 1,462 wins in 4,257 races over twenty-four years, beginning with his first race in AD 122 at age eighteen (although he had raced for two years before his first victory). One thousand sixty-four of these were in singles, in which he raced for himself rather than as a team. He rode nine horses to one hundred victories apiece and one to two hundred. Although there were others who won more victories, Diocles at least lived to enjoy his success. Scorpus, who had 2,048 victories, died in the arena at age twenty-six, his death eulogized by Martial and his gilded busts over all the city (X.74, V.25).

The Circus was the most popular of the diversions provided by the emperor, the diverting panem et circuses which Juvenal satirizes, and its fans fanatical in their devotion to the races. Writing of partisans of Alexandria in the second century AD, Dio Chrysostom describes them as

"a people to whom one need only throw bread and give a spectacle of horses since they have no interest in anything else. When they enter a theatre or stadium they lose all consciousness of their former state and are not ashamed to say or do anything that occurs to them.... constantly leaping and raving and beating one another and using abominable language and often reviling even the gods themselves and flinging their clothing at the charioteers and sometimes even departing naked from the show. The malady continued throughout the city for several days" (Orationes, XXXII, LXXVII).

Originally, professional stables were contracted to provide the necessary horses, personnel, and equipment; in time, these factions (factiones) became increasingly powerful. When Nero increased the number of prizes and races lasted all day, the faction owners (domini factionum), most of whom belonged to the equites, refused to hire out their horses for any less time, terms which one magistrate refused, threatening to have the chariots drawn by dogs rather than meet such an exorbitant demand (Dio, LXI.6.2). This monopoly was potentially threatening and, by the fourth century AD, it had been assumed by the emperor, who alone was to receive the gratitude of the populus in the Circus. Direct management of the factions now passed to their senior charioteers and horses were provided from the imperial stables.

From the time of Augustus, it was in the Circus (as well as in the theater and Colosseum) that the populus could make its opinions known and petition for redress. Cassius Dio was at the Circus in AD 196, during the last chariot races before the Saturnalia, and relates the displeasure of the people at the continuing civil war between Septimius Severus and his rival Albinus. There, the plebs, safe in the anonymity of the huge crowd, began to shout, "How long are we to suffer such things...How long are we to be waging war?" The emperor did well to heed such demonstrations of popular will and to indicate his civilitas (deference) at least by listening to them. For this reason, he was expected, not only to attend the games, but appear to enjoy them (Julius Caesar and Marcus Aurelius both were reproached for being preoccupied with their correspondence), and it is not coincidental that the Circus was built next to the palace on the Palatine Hill.

Although petitions made at the games often were granted, or at least justification offered if refused, there were limits to political expression. Dio relates the deteriorating situation under Caligula, who

"no longer showed any favours even to the populace, but opposed absolutely everything they wished, and consequently the people on their part resisted all his desires. The talk and behaviour that might be expected at such a juncture, with an angry ruler on one side, and a hostile people on the other, were plainly in evidence. The contest between them, however, was not an equal one; for the people could do nothing but talk and show something of their feelings by their gestures, whereas Gaius [Caligula] would destroy his opponents, dragging many away even while they were witnessing the games and arresting many more after they had left the theatres."

Indeed, two years later, in AD 41, Josephus records a demonstration at the chariot races, "to which the Romans are fanatically devoted" (Antiquities of the Jews, XIX.24). There, the assembled crowd implored Caligula to reduce their taxes. But, when the emperor ordered that all those who continued to protest be killed, "the people, when they saw what happened, stopped their shouting and controlled themselves, for they could see with their own eyes that the request for fiscal concessions resulted quickly in their own death." Caligula, himself, was assassinated soon after.

Factions were identified by their colors: Blue or Green, Red or White. Domitian added gold and purple but they, like the emperor, were never popular and short-lived (Dio, LXVII.4.4). Colors first are recorded in the 70s BC, during the Republic, when Pliny the Elder relates that, at the funeral of a charioteer for the Reds, a distraught supporter threw himself on the pyre in despair, a sacrifice that was dismissed by the Whites as no more than the act of someone overcome by the fumes of burning incense (VII.186). According to Tertullian, these were the first two factions and, although the Blues and Greens are assumed to have appeared later in the first century AD (the Greens first are mentioned in an inscription in AD 35, recording the victory of the first man to win on his first attempt), it is likely that all four colors extend back to the Republic. Whatever their origin, by the end of the second century AD, Blue and Green had come to dominate the other two factions, the Blues absorbing the Reds and the Greens, the Whites.

Races always were between factions, who trained the drivers, reared their own horses, and had separate stables, grooms, and trainers, and were hired to compete. If all four factions raced, there would be one, two, or three teams from each (which is why the Circus could accommodate as many as twelve teams). Nero, himself, actually raced, and once, despite being thrown and having to be reposited in his ten-horse chariot at Olympian games in Greece, was declared the winner (Suetonius, XXIV.2), the judges being rewarded one million sesterces for their pronouncement (Dio, LXIII.14.1). Nero postponed the 211th Olympiad in AD 65, so he could compete the following year. Until then, the cycle of four-year Olympiads had not been interrupted in more than eight hundred years. So insulting was his victory that the games were not recorded (Pausanius, X.36.9). The emperors spent fortunes at the races, and bets were laid and race results anxiously awaited. Pliny relates that the head of one faction made the results of a race known by sending birds, whose legs were marked with the color of the winning team, to his home town (X.71).

By the fourth century AD, the number of races had risen to sixty-six days each year. Ammianus Marcellinus (XXVIII.4) complains that the plebs

"devote their whole life to drink, gambling, brothels, shows, and pleasure in general. Their temple, dwelling, meeting-place, in fact the centre of all their hopes and desires, is the Circus Maximus. [They swear] that the country will go to the dogs if in some coming race the driver they fancy fails to take a lead from the start, or makes too wide a turn round the post with his unlucky team. Such is the general decay of manners that on the longed-for day of the races they rush headlong to the course before the first glimmering of dawn as if they would outstrip the competing teams, most of them having passed a sleepless night distracted by their conflicting hopes about the result."

Not surprisingly, later Christian writers inveighed against the Circus, convinced that it was the devil's playground, although, to be sure, it was criticized less than the gladiatorial games or the theater. In De Spectaculis, Tertullian writes (c.AD 200) with the fervor of the converted that the very attraction of the Circus is what makes it so damnable.

"Seeing then that madness is forbidden us, we keep ourselves from every public spectacle—including the circus, where madness of its own right rules. Look at the populace coming to the show—mad already! disorderly, blind, excited already about its bets!....Next taunts or mutual abuse without any warrant of hate, and applause, unsupported by affection....they are plunged in grief by another's bad luck, high in delight at another's success. What they long to see, what they dread to see,—neither has anything to do with them; their love is without reason, their hatred without justice" (XVI).

Three-hundred years later, Cassiodorus, in his Variae, is just as adamant.

"However, this I declare to be altogether remarkable: the fact that here, more than at other shows, dignity is forgotten, and men's minds are carried away in frenzy. The Green chariot wins: a section of the people laments; the Blue leads, and, in their place, a part of the city is struck with grief. They hurl frantic insults, and achieve nothing; they suffer nothing, but are gravely wounded; and they engage in vain quarrels as if the state of their endangered country were in question. It is right to think that all this was dedicated to a mass superstition, when there is so clear a departure from decent behaviour (III.51.11-12)."

Ironically, in their condemnation of the Circus, the Christian apologists provide many details about it that otherwise would be unknown. Tertullian (VIII-IX) asserts that the eggs are symbolic of Castor and Pollux, twins born from Leda's egg; the dolphins, considered by the Romans to be the fastest of creatures, in honor of Neptune, who was patron of the equestrian order and of horses and riders. The chariots are dedicated to the pagan gods: the biga to the Moon, the quadriga to the Sun, and the seiugis to Jupiter. The Whites and Reds represented winter and summer, and were dedicated to Zephyrs and Mars, as the Greens were to the earth (spring), and the Blues to the sky or sea (autumn). In the Etymologies, Isidore of Seville offers more detail still.

Cassiodorus writes of stewards who ride out to announce the beginning of a race, the white break line, and the spina that divided the track. He also relates the origin of the mappa used to signal the start of the race: Once, when Nero had taken too long at lunch and the crowd grew restive, he threw out his napkin from the royal box to signify that he had finished and the games could begin. Cassiodorus is the last to speak of chariot racing in the west.

A century earlier, Rome had fallen to the barbarians, and increasing political instability led to more factional violence. After AD 541, no more consuls were appointed (they could no longer afford the honor in any event) and the burden of sponsoring the races fell to the emperor. But there were other demands on the imperial purse, and the last race in the Circus Maximus is recorded by Procopius to have occurred in AD 550 (Gothic Wars, III.37).

For a thousand years, horses had raced at Rome.

References: Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing (1986) by John H. Humphrey; "The Roman Games" by John H. Humphrey, in Civilization of the Ancient Mediterranean (1988) edited by Michael Grant and Rachel Kitzinger; Sport in Greece and Rome (1972) by H. A. Harris; Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium (1976) by Alan Cameron; Equus: The Horse in the Roman World (1990) by Ann Hyland; Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire (1999) by D.S. Potter and D. J. Mattingly; As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History (1988) by Jo-Ann Shelton; Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome (1969) by J. P. V. D. Balsdon; Daily Life in Ancient Rome (1940) by Jérôme Carcopina; Roman People (1997) by Robert B. Kebric; A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1929) by Samuel Ball Platner; A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (1992) by L. Richardson, Jr.; Rome: An Oxford Archaological Guide (1998) by Amanda Claridge; Pelagonius and Latin Veterinary Terminology in the Roman Empire (1995) by J. N. Adams; Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (1981) by H. H. Scullard; Murray's Classical Atlas (1917) edited by G. B. Grundy.

The Letters of the Younger Pliny (1969) translated by Betty Radice (Penguin Classics); The Roman Antiquities of Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1950) translated by Earnest Cary (Loeb Classical Library); Josephus: Jewish Antiquites (1965) translated by Louis H. Gelman (Loeb Classical Library); Sidonius: Poems and Letters (1936) translated by W. B. Anderson (Loeb Classical Library); Tertullian: Apology and De Spectaculis (1931) translated by T. R. Glover (Loeb Classical Library); Pliny: Natural History (1945) translated by H. Rackham (Loeb Classical Library); Ovid: The Art of Love and Other Poems (1979) translated by J. H. Mozley (Loeb Classical Library); Ovid: Heroides and Amores (1936) translated by Grant Showerman (Loeb Classical Library); Ovid: Tristia and Ex Ponto (1924) translated by Arthur Leslie Wheeler (Loeb Classical Library); Dio's Roman History (1927) translated by Earnest Cary (Loeb Classical Library); Juvenal: The Sixteen Satires (1967) translated by Peter Green (Penguin Classics); Livy: The Early History of Rome (1971) translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt (Penguin Classics); Columella: On Agriculture (1954) translated by E. S. Forster and Edward H. Heffner (Loeb Classical Library); Virgil: Georgics (1935) translated by H. R. Fairclough (Loeb Classical Library); Martial: Epigrams (1968) translated by Walter C. A. Ker (Loeb Classical Library); Aelian: On the Characteristics of Animals (1958) translated by A. R. Scholfield (Loeb Classical Library); Procopius: The Secret History (1966) translated by G. A. Williamson (Penguin Classics); Tacitus: The Annals of Imperial Rome (1959) translated by Michael Grant (Penguin Classics); Tacitus: The Histories (1975) translated by Kenneth Wellesley; Suetonius: The Twelve Caesars (1957) translated by Robert Graves (Penguin Classics); Cassiodorus: Variae (1992) translated by S. J. B. Barnish; Dio Chrysostom: Discourses (1940) translated by J. W. Cohoon and H. Lamar Crosby (Loeb Classical Library).

Additional illustrations have been taken from Rome of the Caesars (1992) by Leonardo B. Dal Maso; Mosaics of Roman Africa (1996) by Michèle Blanchard-Lemée, Mongi Ennaïfer, Hédi Slim, and Latifa Slim; Amphitheatres et Gladiateurs (1990) by Jean-Claude Golvin and Christian Landes; The Oxford History of Classical Art (1993) edited by John Boardman; The Collections of the British Museum (1989) edited by David M. Wilson.

For quadrigae in the circus, there is, of course, the racing scene in Ben Hur (1959), directed by William Wyler.