"to-day they hold shows of their own, and win applause by slaying whomsoever the mob with a turn of the thumb bids them slay..."

Juvenal, Satires (III.36)

In determining the outcome of gladiatorial combat, there is no indication how the crowd demonstrated its verdict regarding the defeated gladiator. Pollice verso translates simply as "turned thumb," but the manner or direction is not known. That the thumb, itself, was regarded as more important than the other fingers of the hand can be seen in its etymology. Macrobius relates the belief that the thumb (pollex) derived its name from the fact that it has power (polleo) (Saturnalia, VII.13.14). The context here is that the thumb is morally superior to the other fingers in that it, alone, disdains the wearing of rings. Lactantius, too, in celebrating the workmanship of God, eulogizes the body's perfection and the thumb's power. "But this is convenient for use, in wonderful ways, that one separated from the rest rises together with the hand itself, and is enlarged in a different direction, which, offering itself as though to meet the others, possesses all the power of holding and doing either alone, or in a special manner, as the guide and director of them all; from which also it received the name of thumb, because it prevails among the others by force and power" (De Opificio Dei, X).

This authority may derive from the notion that the thumb was connected to the genitals, just as the ring finger was thought to be connected to the heart (Aulus Gellius, The Attic Nights, X.10). Fulgentius writes in the Mythologiae ("The Mythologies," III.7), an early fifth-century AD treatise on the allegorical interpretation of myth, that the thumb was connected to the sex organs and, indeed, the erect thumb, in its suggestion of the phallus, was regarded as being apotropaic, i.e., having the power to avert evil.

But it also was perceived as being threatening. Quintilian, in his discussion of rhetorical effect, indicates that "There is also a gesture, which consists in inclining the head to the right shoulder, stretching out the arm from the ear and extending the hand with the thumb turned down. This is a special favourite with those who boast that they speak "with uplifted hand" (Institutio Oratoria, XI.3.119).

Although rendered as "the thumb turned down," the phrase infesto pollice actually translates as "with hostile thumb." It is the same expression used in the Anthologia Latina, a collection of poems made in the early sixth-century AD, where the gesture is identified with the death of the gladiator: "Even in the fierce arena the conquered gladiator has hope, although the crowd threatens with its hostile thumb" (415.27-28).

But if the gesture is hostile in Quintilian, it is just the opposite in Pliny, who relates that "There is even a proverb that bids us turn down our thumbs to show approval" (Natural History, XXVIII.v.25). Here, the phrase pollices premere, which is translated as "turn down our thumbs," signifies approval. It also can be understood to mean "to press down with the thumbs" (i.e., the thumb pressing down upon the closed fist) or, conversely, "to press the thumbs with something" (i.e., pressing with the fingers of the fist so that the thumb is folded within the hand).

There is no clear textual evidence for the position of the thumb, and the Latin does not admit to precise understanding. Horace, for example, speaks of sport being commended "with both thumbs" (Epistles, I.18.66) but the gesture is uncertain. Martial does say that the crowd appealed for mercy by waving their handkerchiefs (XII) or by shouting (Spectacles, X). And both Juvenal, cited above, and the Christian poet Prudentius relate that spectators demanded the deathblow by "turning the thumb." In Juvenal, the phrase is verso pollice; in Prudentius, who rails against the carnage in the arena, converso pollice. "There she [the Vestal Virgin] sits conspicuous with the awe-inspiring trappings of her head-bands and enjoys what the trainers have produced. What a soft, gentle heart! She rises at the blows, and every time a victor stabs his victim's throat she calls him her pet; the modest virgin with a turn of her thumb bids him pierce the breast of his fallen foe" (Against Symmachus, II). In gesturing toward the heart to indicate that the gladiator was to be dispatched, the thumb would seem to mimic the sword, the thumb signaling life or death by being hidden in the fist or extended.

Corbeill provides the most thorough review of the gesture. Translating pollices premere in Pliny as "to press the thumbs," he concludes that the thumb pressed down on the index finger of the closed fist signified mercy. The opposite gesture was the erect thumb pointing upward, which is how he understands infesto pollice in Quintilian. Here, the hostile thumb signified death. Indeed, this is the definition of pollex in Lewis and Short (A Latin Dictionary, 1880): "To close down the thumb (premere) was a sign of approbation; to extend it (vertere, convertere; pollex infestus) a sign of disapprobation."

More intriguingly, Corbeill suggests that it was not the victorious gladiator who was expected to determine the reaction of the crowd but the producer (editor) of the games, who conveyed the verdict to the judge. His attention, contends Corbeill, would have been gained by music being played in the arena, perhaps the note of a horn, as can be seen in the Zliten mosaic.

The Médaillon de Cavillargues (above) is used by Corbeill to support his contention that the thumb pressed down on the fist was a gesture of mercy. He suggests that the rod is not being held by the person on the right but by the one in the middle, thereby freeing the fist to signify a gesture of mercy.

And indeed, at the top of the medallion there is the inscription STANTES MISSI, "released standing," signifying missio or release from the arena for the two combatants, who are identified by placards in the background as Xantus, victor in fifteen contests, and Eros, victor in sixteen. The medallion, which depicts a contest between a retiarius and a secutor, dates to the late second or early third century AD and is in the Musée Archéologique (Nîmes).

"He would not allow women to view even the gladiators except from the upper seats, though it had been the custom for men and women to sit together at such shows. Only the Vestal virgins were assigned a place to themselves, opposite the praetor's tribunal."

Suetonius, Life of Augustus (XLVI)

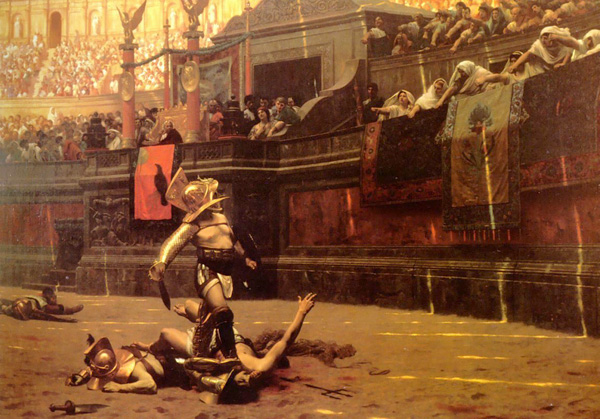

In Pollice Verso (1872) above by Jean-Léon Gérôme (Phoenix Art Museum), the Vestals signify death to the fallen gladiator. Translated as "Thumbs Down," the picture perpetuated that mistaken notion. It also inspired Gladiator (2000), where Ridley Scott was obliged to have Commodus indicate "thumbs up" in sparing Maximus.

References: "Thumbs in Ancient Rome: Pollex as Index" (1997) by Anthony Corbeill, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 42, 61-81; Nature Embodied: Gesture in Ancient Rome (2004) by Anthony Corbeill; The Lives of the Twelve Caesars (1914) translated by J. C. Rolfe (Loeb Classical Library); Horace: Epistles (1926) translated by H. Rushton Fairclough (Loeb Classical Library); Pliny: Natural History (1938-) translated by H. Rackham et al. (Loeb Classical Library); The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325 (Vol VII: Lactantius) (1885-1896) translated and edited by the Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson; Fulgentius the Mythographer (1971) translated by Leslie George Whitbread; Quintilian: The Orator's Education (2001) translated by Donald A. Russell (Loeb Classical Library); Martial: Epigrams (1993) translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey (Loeb Classical Library); Fulgentius the Mythographer (1971) translated by Leslie George Whitbread; Das Spiel mit dem Tod: So Kämpften Roms Gladiatoren (2000) by Marcus Junkelmann.