Return to the Battle of Hastings

"The monks came to meet them [Normans], asked them for peace, but they did not care about anything, went into the minster, climbed up to the holy rood, took the crown off our Lord's head—all of pure gold—then took the rest which was underneath his feet—that was all of red gold—climbed up to the steeple, brought down the altar-frontal that was hidden there—it was all of gold and of silver. They took there two golden shrines, and 9 silver, and they took fifteen great roods, both of gold and of silver. They took there so much gold and silver and so many treasures in money and in clothing and in books that no man can tell another."

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Peterborough MS)

Aside from the obvious political consequences of the Norman Conquest, there was an immediate impact on Anglo-Saxon art, a plundering of the country's cultural heritage that the Normans sought to justify.

William of Poitiers, an Anglo-Norman historian, writes of England's wealth.

"Treasures remarkable for their number and kind and workmanship had been amassed there, either to be kept for the empty enjoyment of avarice, or to be squandered shamefully in English luxury. Of these he [William] liberally gave a part to those who had helped him win the battle, and distributed most, and the most valuable, to the needy and to the monasteries of various provinces."

And, indeed, once the countryside had been subjugated, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Worchester MS) records for the year 1070 that "in the following spring the king allowed all the minsters which were in England to be raided."

Much of the ecclesiastical art despoiled from English churches went to enrich those of Rome and France, especially William's own duchy of Normandy. William of Poitiers boasts of the amount of art that went overseas.

"In a thousand churches of France, Aquitaine, and Burgundy, and also Auvergne and other regions, the memory of King William will be celebrated forever....Some churches received very large golden crosses, wonderfully jewelled; many others pounds of gold, or vessels made of the same metal; quite a few vestments or something else of value."

William's conquest, says his biographer, was greater even than that of Caesar. He

"rewarded this dutiful affection immediately with treasures of many kinds, giving vestments, gold bullion, and other magnificent gifts to the altars and servants of Christ....To the basilica of Caen...he brought such diverse gifts, so precious in both material and workmanship that they deserve to be remembered to the end of time. It would take too much space to describe or even to enumerate each one."

And yet, one cannot ignore the unintended irony in the attempt by William of Poitiers to glorify the Conqueror.

"There are some powerful men who endow the saints wickedly, for the most part increasing with these gifts their glory in the world and their sins before God. They despoil churches and enrich others with booty. But King William won true fame through his goodness alone, by giving only the things that were truly his."

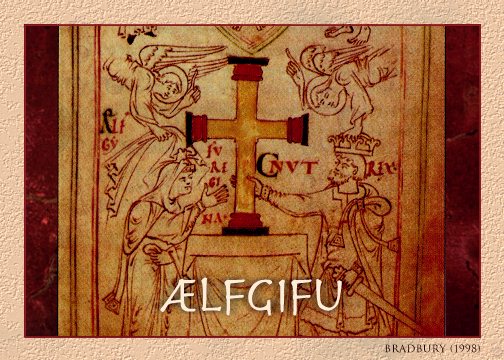

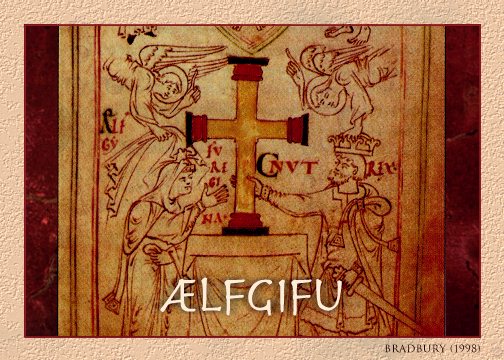

The drawing above dates from about 1020 and depicts Queen Emma, the mother of Edward, and her husband Cnut presenting a massive gold altar cross to the New Minster at Winchester. In the manuscript, her name can be seen to be Ælfgifu (elf's gift).

That had been the name of Æthelred's grandmother, the sainted wife of King Edmund, and was bestowed upon Emma when she married Æthelred, just as it had been given to his first wife and to their daughter. It was this Ælfgifu who was married to Uhtred, Earl of Bamburgh (Northumbria), to assure the loyalty of that powerful northern family. He died in 1016, treacherously killed by Cnut in his contention for the English throne, the same year that he took the widowed Emma as his wife. Half a century later, during Christmas 1064, Gospatric, Uhtred's son by a previous marriage, was murdered at court, allegedly at the instigation of Queen Edith, the wife of Edward, on behalf of her brother Tostig, whose repressive rule of Northumbria had provoked a rebellion there.

Ælfgifu also was the name of Emma's great rival, Cnut's mistress, Ælfgifu of Northampton. "The other Ælfgifu," as she is dismissively characterized by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, was the mother of Harald Harefoot, who assumed the English throne on the death of his father, usurping it from his half-brother Harthacnut, Emma's own son by Cnut.