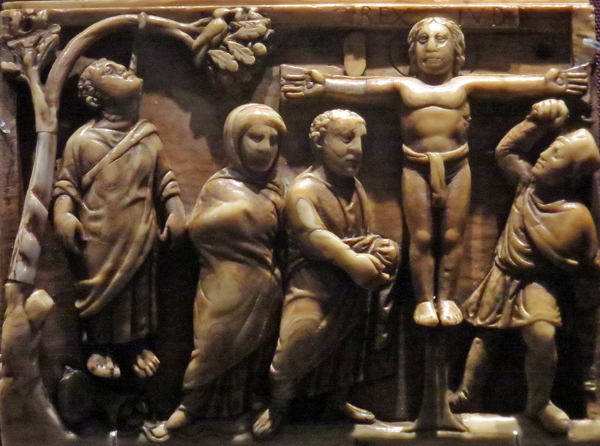

This small ivory panel, which dates to AD 420–430, is the earliest portrait of the Crucifixion in a narrative context. Here, Jesus gazes impassively pass the viewer, flanked by Mary and John and Longinus, the Roman centurion who pierced his side (John 19:34), later exclaiming, "Truly this man was the Son of God" (Matthew 27:54, Mark 15:39).

Behind the head of Jesus, there is a nimbus and an inscription, REX IVD[AEORUM], "King of the Jews." The body is muscular and the feet unsupported by a suppedaneum, the bar that projected from the base of the cross. In contrast, Judas hangs limply from a tree, a bag of spilled coins at his feet, his own eyes closed and feet drooping lifelessly. In the branches, a nesting bird feeds its newly-hatched chicks, symbolizing the renewal of life wrought by Jesus' death. As Harly-McGowan stresses, it is not the fact of Jesus' death that is emphasized but his victory over it.

There is one other fifth-century representation of the crucifixion, on a carved wooden panel on the door of the church of Santa Sabina in Rome that dates to about AD 432. The earliest depiction of a crucified Jesus, however, is carved on a magical amulet from the eastern Mediterranean dated to the late second or early third century AD. Seemingly an incongruous association, the image may have evoked magical power—as Origen noted: "Such power, indeed, does the name of Jesus possess over evil spirits, that there have been instances where it was effectual, when it was pronounced even by bad men" (Against Celsus, I.6).

The panel is one of four carved ivory reliefs, collectively known as the Maskell Passion Ivories, that once formed the sides of a casket or reliquary. Part of the collection of William Maskell, a medievalist and ecclesiastical antiquary, who authored Ivories: Ancient and Medieval (1876), they were acquired by the British Museum in 1856 with a special grant from the Treasury.

Only the four side panels of the box survive and even the one depicting the Crucifixion is damaged. One can see, for example, that the trunk of the tree has been repaired and that the soldier's spear is missing.

The spilled coins signify both the avarice and betrayal of Judas (Matthew 26:15), which led to his suicide by hanging—just as Hannibal Lecter had lectured in the movie Hannibal (2001). So, too, is Judas Iscariot assigned by Dante in the Inferno (Canto XXXIV) to the fourth and final ring of the ninth circle of Hell, where the most evil of sinners are tormented: those who have betrayed their benefactors.

References: "The Maskell Passion Ivories and Greco-Roman art: Notes on the Iconography of Crucifixion" (2013) by Felicity Harley-McGowan, in Envisioning Christ on the Cross: Ireland and the Early Medieval West, edited by Juliet Mullins, Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh, and Richard Hawtree; "Death is Swallowed Up in Victory" (2011) by Felicity Harley McGowan, Cultural Studies Review, 17(1), 101-124; "The Crucifixion" (2007) by Felicity Harley-McGowan, in Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art edited by Jeffrey Spier.