"Who has the skill to unfold the countless embellishments and forms, and to display the architectural beauties of each demesne?....these lofty mansions to be the river's ornament....What need to make mention of their courts set beside verdant meadows, of their trim roofs resting upon countless pillars? What of their baths, contrived low down on the verge of the bank?"

Ausonius, The Moselle (298ff)

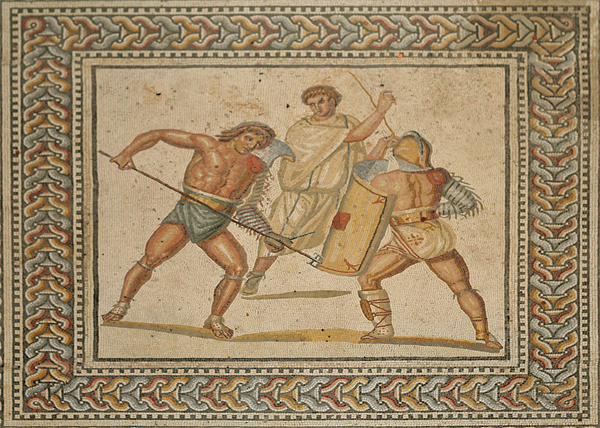

Located in Perl-Nennig south of Trier, this gladiatorial mosaic is one of the most important Roman artifacts north of the Alps (another is the mosaic at the R÷merhalle, Bad Kreuznach). It graced the entrance or reception hall (atrium) of a palatial villa which, like those praised by Ausonius, was situated on a slope of the Mosel valley. Because the site is a bit remote, the mosaic is described in detail. As can be seen, the elaborate pattern of geometrical designs is comprised of seven octagonal medallions surrounding two central quadrangles, one decorated with a scene of gladiatorial combat, the other occupied by a marble basin at the original entrance to the hall.

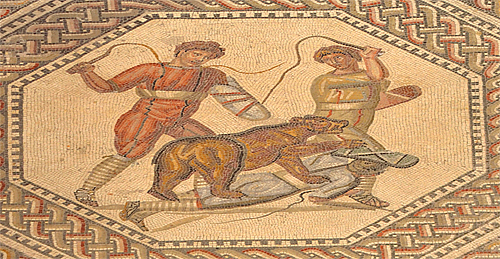

Mortally wounded, the leopard tries to pull the javelin out of its side but succeeds only in breaking it off. The venator, his left arm protected and another spear in his hand, acknowledges the acclamation of the crowd.

A female tiger has brought down a wild ass and looks about before beginning her feast.

This was the first of the illustrated panels to be discovered (in 1853) and depicts a resentful lion, with only the head of the ass still is in his possession, being led away by his aged keeper.

A respite from the animal fights, two combatants attack one another with cudgels and a whip, the smaller man seemingly at a disadvantage but no doubt more cunning.

In this scene, which is in the center of the mosaic and so hopelessly oblique to the viewer, a bear has thrown one of his tormentors to the ground, while two confederates try to drive the animal off by lashes from their whips.

The beginning and conclusion of the games would be announced by music, in this case a water organ (hydraulus), in which water pressure pushed the air through the bronze pipes. Pumps on each side of the hexagonal base contained hydraulic pistons, the levers that drive them visible below the cylinders.

The curved horn, which is braced and supported on the shoulder of the player by a cross bar, is a cornu.

The concluding contest of the games, and its highlight, depicts combat between a retiarius and secutor. A large marble basin at the entrance to the atrium occupies the complementary square opposite.

The medallion at the entrance to the hall has been destroyed, perhaps intentionally, by later occupants of the villa. In its place is a modern inscription indicating that the mosaic was discovered in 1852, reconstructed in 1874, and completely restored in 1960, when the mosaic was reset on pillars to protect it from ground water. A coin from the time of Commodus, who ruled from AD 180-192, found during the restoration provides a terminus post quem for the villa no earlier than the last quarter of the second century, although the site itself had been inhabited at least two centuries before. In excavations between 1866 and 1876, only part of the main building and the extensive grounds were uncovered, but the symmetry of the ground plan allows them to be reconstructed.

A portico ran across the fašade of the main building, terminating in two forward wings that flanked a central courtyard, and then extended on either side along two covered walkways. The building and grounds must have been truly magnificent, especially given the bucolic setting and a view, now obscured by the houses of the village, of the hills on the other side of the river. The principal colonnade was almost 460 feet long and each of the walkways continued another 820 feet, one leading to a therma that had a large indoor swimming pool and heated rooms for bathing.

Regrettably, the model above and its large protective case have been placed directly in front of the gallery above the mosaic, which make it difficult to take pictures along its axis. Too, the large size of the mosaic, which measures approximately 34 by 51 feet, introduces errors in vertical perspective, which have been partially corrected.

References: The Roman Mosaic at Nennig: A Brief Guide (n.d.) by Reinhard Schindler; Ausonius (1921) translated by Hugh G. Evelyn White (Loeb Classical Library).