The most readily identifiable of all the gladiators, the retiarius became popular in the middle of the first century AD, when he was paired against the secutor. Naked except for a loincloth (subligaculum), which was held in place by a wide belt (balteus); a manica or arm-guard on his left arm, so the right would be less encumbered; and the galerus or shoulder-guard, the retiarius carried a weighted throwing net (rete), a three-pronged trident (tridens or fuscina), and a short sword or dagger (pugio) which he held in his left hand. Still, the retiarius was the most lightly armed of the gladiators.

(Valerius Maximus, I.7.8, tells the curious story of a spectator who dreamed of being killed while attending the games. Relating the event the next day to those sitting nearby, he saw the face of the gladiator who he dreamed had killed him. Dissuaded from leaving his seat, the man watched as a retiarius forced a murmillo to a spot nearby and threw him down. Attempting to stab his opponent with a dagger, he ran the hapless equites through instead.)

Without a mask to hide his face from the shame, his trident and net more emblematic of the sea than the conventional arms of the soldier, which formed the military context of other gladiatorial categories, the retiarius is a curious figure, inferior in rank and dignity because of his poor weapons and half-naked vulnerability.

There also is an association with homosexuality and effeminacy. Juvenal relates the story of Gracchus, a aristocratic descendant of the Gracchi, who became the male bride of a horn player (II.1.17ff). But more disgraceful than this affair was that he also fought in the arena as a gladiator, not as a murmillo but assuming the trident and tunic of the retiarius (II.143ff). As a retiarius tunicatus, he missed a throw of the net and was obliged to run for his life (VIII.199ff), the ribbon of his conical hat, presumably an indication that he was a Salian priest, streaming behind him. So mortifying is the display that even the secutor who fought Gracchus is ashamed to be matched against such a person. Inveighing against women in Book VI, Juvenal complains that a lanista manages a cleaner house than one which allows such a person to reside there. At least, the trainer separates the vile from the decent, sequestering "from their fellow-retiarii the wearers of the ill-famed tunic (Oxford1ff).

Seneca is more emphatic, if less specific. In Natural Questions (VII.31.3), he complains about the increasing effeminacy of men and the indignities to their virility. "One man cuts off his genitals, another flees to an indecent part of the gladiator's school; and, hired for death, he chooses a disgraceful type of armament to practice his sickness in." The implication is that there was a class of gladiator, or rather, pseudo-gladiator, who fought in mock combat as part of a comic spectacle.

If so, this explains a strange passage in Suetonius, where, in the only other mention of the term, he recounts that "Once a band of five retiarii in tunics, matched against the same number of secutores, yielded without a struggle; but when their death was ordered, one of them caught up his trident and slew all the victors. Caligula bewailed this in a public proclamation as a most cruel murder, and expressed his horror of those who had had the heart to witness it" (Life, XXX.3). Certainly, the triumph of a lone retiarius tunicatus against the secutors would have inverted the normal order. It also may explain a remark in the Satyricon of Petronius, where Encolpius, the narrator, is called a gladiator obscene (IX), which presumably is a reference to his having been in that indecent part of the gladiator school mentioned by Seneca.

Gracchus willingly entered the arena as a retiarius tunicatus, just as other men of the senatorial and equestrian orders forfeited their rank and civil privileges "so as not to be prevented by the decree of the senate from appearing on the stage and in the arena" (Suetonius, Tiberius, XXXV.2). And, just as Gracchus was exposed and recognizable, his face turned to the crowd, so equites were allowed to fight as gladiators, to exhibit both their vanity and contempt for disgrace. "In this way they incurred death instead of disfranchisement; for they fought just as much as ever, especially since their contests were eagerly witnessed, so that even Augustus used to watch them in company with the praetors who superintended the contests" (Dio, LVI.25.7).

One is reminded, too, of a line from Seneca (On Mercy, I.22), "No one is sparing of a ruined reputation; it brings a sort of exemption from punishment to have no room left for punishment."

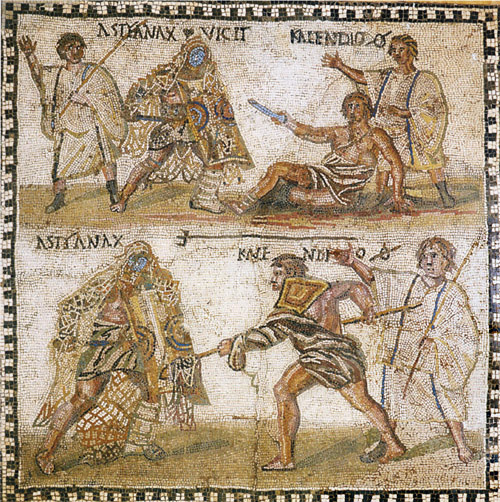

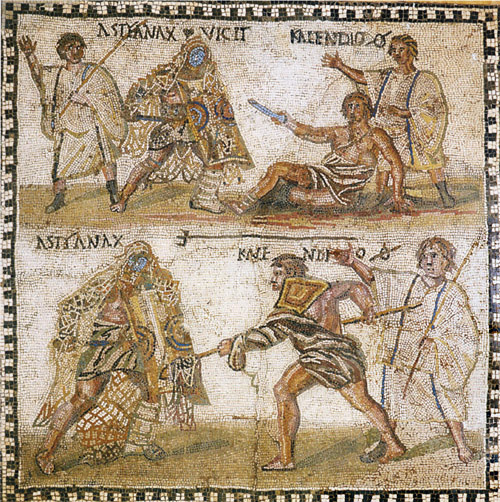

In the mosaic, which is in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional (Madrid), the retiarius, having thrown his net, attacks a secutor with his trident. The referee stands by, awaiting the outcome.

Reference: Das Spiel mit dem Tod: So Kämpften Roms Gladiatoren (2000) by Marcus Junkelmann; "The Retiarius Tunicatus of Suetonius, Juvenal, and Petronius" (1989) by Steven M. Cerutti and L. Richardson, Jr., The American Journal of Philology, 110, 589-594; Seneca: Naturales Quaestiones (1972). translated by Thomas H. Corcoran (Loeb Classical Library); Suetonius: The Lives of the Caesars (1914) translated by J. C. Rolfe (Loeb Classical Library); Dio Cassius: Roman History (1927) translated by Earnest Cary (Loeb Classical Library); Seneca: Moral Essays (1928) translated by John W. Basore (Loeb Classical Library).