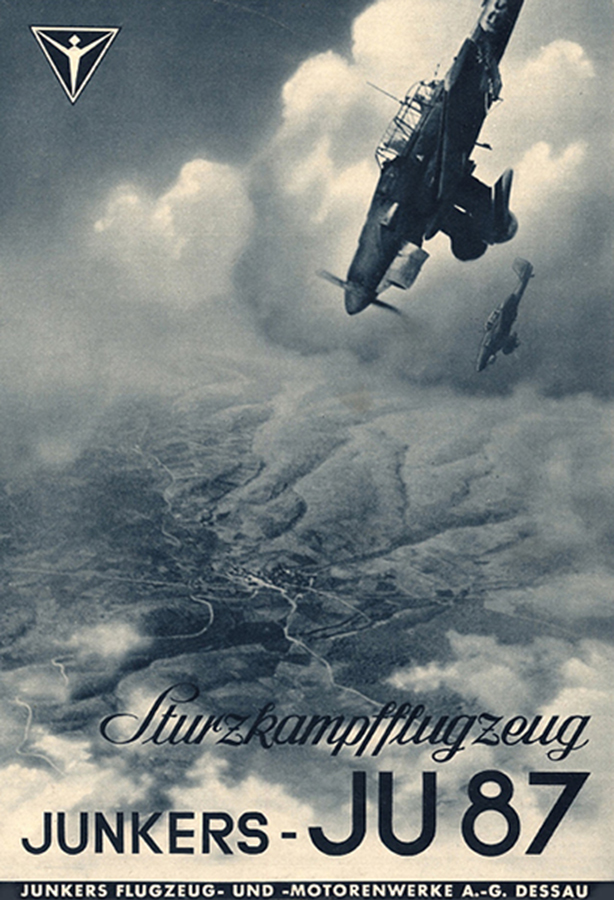

Junkers Ju 87 Stuka

From September 1939 through May 1940, the Stuka flew unopposed over Poland, the Low Countries, and eastern France, where panicked refugees and retreating troops had been terrified by the banshee wail of its sirens. With the air forces of these countries destroyed, it was the Stuka pilot, spearheading the Blitzkrieg, who was the darling of the propaganda newsreel. Taking the place of heavy ground artillery in support of the army, the plane itself was robust, relatively inexpensive to build, and easy to maintain in the field. It could carry a 500-pound bomb under the fuselage and four 110-pound bombs beneath the wings, all delivered with an accuracy unmatched at the time.

But the Ju 87 also was slow (which is why its sirens largely had been removed by the Battle of Britain); indeed, with a top speed of about 230 mph (and a cruising speed of 160 mph), it was the slowest operational aircraft in the Battle. With only two machine guns of its own in front and a single gun facing aft, the plane was vulnerable when confronted by the eight guns of a Spitfire or Hurricane, especially given its slow rate of climb or pulling out of a dive, when it was subject to ground fire as well. Not only was the Stuka unable to adequately protect itself, but it could not be easily defended by anyone else. The Bf 109 that escorted the plane was more than 150 mph faster than its lumbering charge and at its best above 20,000 feet. Indeed, to conserve fuel, the fighters had to wait until the planes were half-way across the Channel before taking off and even then were obliged to fly in a zig-zag pattern to stay with them. Too, because the Stukas began their steep dive from 13,000 feet and released their bombs at about 1,200 feet, the fighters had to fly at a much lower altitude, depriving them of their greatest advantages—speed and height.

The Ju 87 were constructed in great numbers and represented a substantial portion of the Luftwaffe's strength. It therefore could hardly not be used. But when confronted by modern fighters in a theater where air superiority had not been established (which, of course, was the whole point in the Battle of Britain) the plane was vulnerable. On August 13, 1940 (Adlertag, the first day in a series of attacks intended to destroy RAF Fighter Command prior to invasion), six of nine Ju 87Rs were lost (and one damaged) from a Staffel of II/St.G 2. (The Ju-87R was a long-range variant that carried two large drop-tanks beneath the wings, which must have made the plane even more unwieldy.) Two days later, Göring issued a new directive to all Luftwaffe commanders.

Each Stuka now was to have no less than three Bf 109 fighters for its protection: one Gruppe to remain with the planes even as they dived, another to fly overhead at medium altitude and engage the enemy, and a third to protect the overall attack from above. It was the equivalent of an entire Gruppe supporting a single Staffel. On August 18, there was the largest concentration of Stukas ever assembled for a single raid on the island. It was "The Hardest Day," in which two entire Luftflotten were directed at the sector airfields of No.11 and No.12 Group. In spite of Göring's directive, Stukas from I/St.G 2 could not be protected and were mauled: sixteen were shot down, two crashed on the return home, and four others were damaged. Aside from some incidental attacks on British convoys later that year and early the next, the bloodied Ju 87 finally was withdrawn from combat and reassigned to the Balkans and Crete—and then to North Africa.

It is there, in the Italian colony of Libya, that the "Snake" Stuka was to be seen.

Captured near the Russian border, the Ju 87 pictured above is on display at the RAF Museum (Hendon) outside London and is one of only two surviving examples. It originally was built as a D-3 Trop ground attack variant (above the exhaust pipes, one can see a filter built into the air intake) but later modified as a G-2 with the installation of outer wing sections. Fittings for dive brakes, bomb and drop tanks all were removed and mounts for two Flak 18 37mm anti-tank canon installed. Captured at the end of the war in May 1945, the plane was selected for museum display rather than evaluation and originally was in mottled gray camouflage. Later, in 1967 it was repainted for possible use in the film Battle of Britain. Even though the engine fired and the plane even may have taxied, it was deemed too expensive to be made completely airworthy.

The other surviving plane, a R-2 Trop, was found abandoned by British forces in 1941 after a forced landing in Libya (one still can see the bullet holes in the fuselage). It now is in the Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago) as a static display (the engine is in another gallery). Originally part of an American tour of war prizes sponsored by the British Information Service, it was donated to the museum in 1945 (as was the Spitfire hanging behind it). The closely fitted wheel spats had been removed, as often was the case when the plane operated in rough terrain, especially when mud, dust, or snow could accumulate inside the spats and prevent the wheels from rotating freely.