Like all cones snails, C. marmoreus ("Marbled Cone") is predatory and uses a venomous sting both to defend itself and hunt other mollusks. But its barbed radular tooth, which is used to attack its prey, is much shorter than those of other molluscivores and comparable in length to that of vermivores, which hunt marine worms. And, just as this guild has not accounted for any verifiable human fatalities, nor has C. marmoreus—in spite of what one might read.

In an important study summarizing a lifetime of work, Kohn reviewed 141 envenomations reported between 1670 and 2017, during which time there have been three dozen deaths and more than one hundred injuries from cone stings. But only six stings have been attributed to C. marmoreus and none have been verifiable fatalities. As Endean and Rudkin concluded, the mollusk is not a potential danger to humans.

The truly dangerous cones are piscivorous and hunt fish, which must be instantly paralyzed if they are not to escape or injure the snail itself in the attempt. And of these, the most lethal species is Conus geographus ("Geography Cone"), which accounts for more than half of human envenomations and, according to Kohn, "all or most of the human fatalities." It is the largest of the piscivores and reported to have caused three dozen fatalities in the past three-and-half centuries.

C. marmoreus was the first species of cone shell to be described by Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae (10th ed., 1758, no. 250, p. 712), who used the specimen in his own collection as the lectotype. As the type species, it therefore defines the genus Conus—and so, the species that properly belong to it.

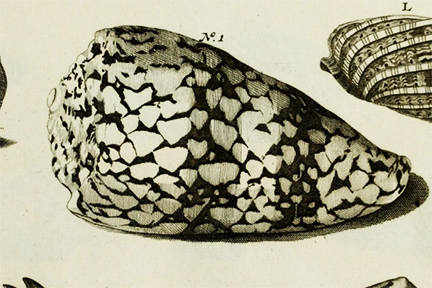

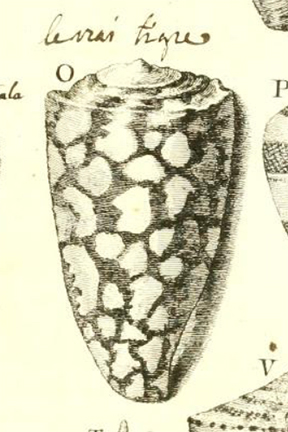

The illustrations are from Rumphius' Thesaurus (1711, Pl. XXXII, No. 1), where the low coronate spire is described as Harts-hoorn met banden (p. 7), and d'Argenville's La Conchyliologie (1742, Pl. XV, Fig. O, p. 281), both of which Linnaeus referenced in his description.

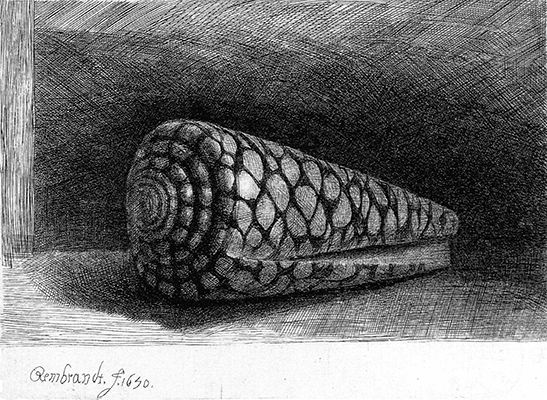

This etching (The Shell, 1650), which survives in relatively few impressions, is the only example of an object from Rembrandt's cabinet of curiosities and his only still-life. As often was the custom, Rembrandt drew the shell as he saw it. But, incised on the plate, the image is reversed on the pulled paper and so appears as a mirror image of itself, with the aperture on the left (as it would in a sinistral shell) rather than on the right—even though the plate has been signed and dated correctly.

In March 1637, Rembrandt purchased a conch shell for the extravagant sum of eleven guilders. It was such acquisitions that contributed to his bankruptcy in 1656, when all his belongings were auctioned, including "a great quantity of shells [and] coral branches."

A note on nomenclature: The family Conidae comprises only one genus Conus, which more popularly is known as the cone snail or cone shell (the study of the former is malacology; the later, conchology). All these mollusks are venomous, which is to say that they inject their toxin. A poisonous animal (such as the blowfish) must be ingested for its toxin to take effect. And, although "bite" often is used for convenience, the harpoon-like tooth of the cone snail is not comparable to that of a vertebrate, and "sting" is a more accurate description of the pricking of the skin.

Lesson XII:

Teacher. If any one were now to speak to you of a Conus, what idea would the name call up to your mind?

Child. The name Conus would recall the idea of a univalve shell, whose form is inversely conical and turbinate; the spire retuse; whorls spirally convoluted, aperture linear, longitudinal, entire, effuse at the base; its columellar lip smooth, having sometimes a few oblique rugose striæ towards its base.

Teacher. Yes, all the shells before us posses these qualities, or they would not be Cones:—but are they alike in all respects?

Child. No ; they differ very much in their colours and patterns, and also in their size.

Teacher. On account of this variety in the shells possessing the same generic marks, the different genera have been subdivided into species, the characters of which are determined by—the circumstances of colour, markings, size, and the inequalities of the surface. Here is a shell called Conus marmoreus: I wish you to examine it, and draw out its specific character; it is considered as the type or representative of the Conus, from its having the characteristics of the genus strongly marked. Now, tell me what you have to do.

Child. We must try and describe this shell.

Teacher. Yes; but you must recollect that you have to point out the specific distinctions only; you must now omit the generic marks, as you have already determined them, and they are implied in the name Conus. First, what is the size of this Cone?

Child. It is rather more than two inches long.

Teacher. Yes, in length it generally varies from two to three inches. What is the colour of the shell, and that of its markings?

Child. The ground is a dark chestnut brown, approaching to black, and the markings are white.

Teacher. What form do the spots most nearly resemble?

Child. They are nearly triangular.

Teacher. You may call them white subtriangular spots; sub means under, and when prefixed to an adjective implies that the quality attributed to the object, exists in an inferior degree. Examine the substance of the shell.

Child. It is heavy and thick.

Teacher. It is a ponderous shell; now look at the spire, and tell me what you remark in it.

Child. It has little swellings placed regularly at the edges of the whorls.

Teacher. These swellings are called tubercles, and a spire marked with such inequalities is said to be coronated.

Child. I suppose that means crowned.

Teacher. Yes, the spire is so called from its crown-like appearance; do you observe any other peculiarity in it?

Child. The whorls are concave, and in most shells they are convex.

Teacher. The whorls in this shell form a little spiral channel, and are thence said to be channelled. We will now write down the specific character; but I must inform you, that the name marmoreus is derived from the Latin marmor, marble; and is applied to these shells on account of their mottled appearance.

Lessons on Shells, As Given to Children Between the Ages of Eight and Ten, in a Pestalozzian School, at Cheam, Surrey (1838, 2nd ed.) by Elizabeth Mayo

References: Linnaeus: Systema naturae (1758); Manual of the Living Conidae (1995) by Dieter Röckel, Werner Korn, and Alan J. Kohn; "Human Injuries and Fatalities due to Venomous Marine Snails of the Family Conidae" (2016) by Alan J. Kohn, International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 54(7), 524-538 (Online Supplement); "Conus Envenomation of Humans: In Fact and Fiction" (2019) by Alan J. Kohn, Toxins, 11(1), 10, online; "Snail Spears and Scimitars: A Character Analysis of Conus Radular Teeth" (1999) by Alan J. Kohn, Manami Nishi, and Bruno Pernet, Journal of Molluscan Studies, 65, 461-481; "Studies of the Venoms of Some Conidae" (1963) by R. Endean and Clare Rudkin, Toxicon, 1, 49-64; "Venomous Marine Snails of the Genus Conus" (1963) by A. J. Kohn, in Venomous and Poisonous Animals and Noxious Plants of the Pacific Area edited by Hugh L. Keegan and W. V. Macfarlane; "The Poison Cone Shell" (1943) by William J. Clench and Yoshio Kondo, American Journal of Tropical Medicine, 23, 105-122; "Clinical Toxicology of Conus Snail Stings" by Lourdes J. Cruz and Julian White, in Handbook of Clinical Toxicology of Animal Venoms and Poisons (1995) edited by Jürg Meier and Julian White; "Preliminary Studies on the Venom of the Marine Snail Conus" (1960) by A. J. Kohn, P. R. Saunders, and S. Wiener, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 90(3), 706-725; La lithologie et la conchyliologie (1742) by [Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d'Argenville]; Thesaurus imaginum piscium testaceorum; ut & cochlearum; quibus accedunt conchylia, denique mineralia (1711) by Georgius Everhardus Rumphius

In the online supplemental materials to Kohn's article in the International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, there are six spreadsheets documenting human injuries due to Conus envenomation from 1670 through 2017. But in SM1, which summarizes these injuries, there seems to be an error. The outcome of Case No. 112 (marmoreus) is designated "A," signifying the severity of the injury to have been fatal. But in the citation to Hawaiian Shell News (Aug. 1988), 36(8), p. 4, which reported the incident, the victim's finger was "a bit sore for a day or two, did not swell and the two nicks soon healed." The designation therefore should be "C," signifying minor effects only (comparable to a bee sting).