"It is a small white Silver-shining Worm or Moth, which I found much conversant among Books and Papers, and is suppos'd to be that which corrodes and eats holes through the leaves and covers; it appears to the naked eye, a small glittering Pearl-colour'd Moth, which upon the removing of Books and Papers in the Summer, is often observ'd very nimbly to scud, and pack away to some lurking cranney, where it may the better protect itself from any appearing dangers....This Animal probably feeds upon the Paper and covers of Books, and perforates in them several small round holes, finding, perhaps, a convenient nourishment in those hulks of Hemp and Flax, which have pass'd through so many scourings, washings, dressings and dryings, as the parts of old Paper must necessarily have suffer'd; the digestive faculty, it seems, of these little creatures being able yet further to work upon those stubborn parts, and reduce them into another form. And indeed, when I consider what a heap of Saw-dust or chips this little creature (which is one of the teeth of Time) conveys into its intrals, I cannot chuse but remember and admire the excellent contrivance of Nature."

Robert Hooke, Micrographia (Observation LII)

Robert Hooke was a fellow of the Royal Society (founded by Charles II in 1660, only six months after his restoration) and its first Curator of Experiments, which were conducted at weekly meetings of the Society. In 1665, these demonstrations, illustrated by a series of exquisite copper-plate etchings based on Hooke's drawings, were published by the Society, the second book printed under its imprimatur, preceded only the year before by John Evelyn's Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber.

Having seen Micrographia while still at the binder's, the diarist Samuel Pepys thought it "so pretty that I presently bespoke [ordered] it" (Diary, January 2, 1665). When the book arrived at his bookseller several weeks later, he pronounced it "a most excellent piece, and of which I am very proud" (January 20). Indeed, the next day, he stayed up until two o'clock in the morning reading it, declaring "Mr. Hooke's Microscopicall Observations, the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life" (January 21). Less than a month later, Pepys himself was admitted as a fellow of the Society, where there were "very fine discourses and experiments, but I do lacke philosophy enough to understand them" (March 1). Notwithstanding, he would become its president in 1684.

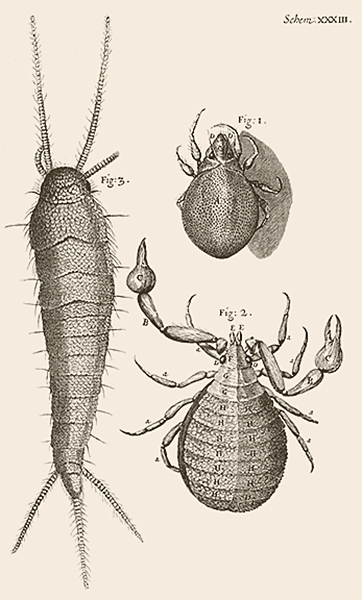

In the passage above, Hooke is describing the silverfish (Figure 3): Lepisma saccharina, from its fondness for the starches and sugars in book bindings and paste, although the popular name was not applied to the insect for another two hundred years.

The "Crab-like Insect" illustrated in Figure 2 was observed one day as it slowly crept over a book Hooke was reading. It was the only one he had ever seen and, observing it through an early compound microscope of his own devising, he marveled that "Nature had crouded together into this very minute Insect, as many, and as excellent contrivances, as into the body of a very large Crab" (Observation LI). This was the "book scorpion" (Chelifer concroides), so named for the two claws with which it hunts book-lice (Liposcelis divinatorius)—which, like silverfish, feed on the starchy paste used by bookbinders. Of the claws, "it carried these aloft extended before, moving them to and fro, just as a man blindfolded would do his hands when he is fearfull of running against a wall." Aristotle had mentioned the insect more than two thousand years earlier in the History of Animals: "the scorpion is furnished with claws, as is also the creature resembling a scorpion found within the pages of books" (IV.7). Figure 1 likely illustrates Phauloppia lucorum, an oribatid or "wandring mite" as Hooke described it, one of "several of these little pretty Creatures" that he observed crawling to and fro over the panes of his window and in the moss on the wall outside (Observation L).

Weiss and Carruthers provide an annotated bibliography of almost five hundred titles on insect damage to books, of which twenty are from the classical period. Half of these references do not speak of bookworms, however, but to their prevention, usually by the application of cedar oil (e.g., Ausonius, Epigrams, XIX.1; Persius, Satires, I.42; Pliny, Natural History, XXIV.xi17; Vitruvius, On Architecture, II.13).

There even is an epigram to the bookworm by Evenus (of Ascalon), one of several poets in the Greek Anthology with that name—

"Page-eater, the Muses' bitterest foe, lurking destroyer, ever feeding on thy thefts from learning, why, black bookworm, dost thou lie concealed among the sacred utterances, producing the image of envy? Away from the Muses, far away! Convey not even by the sigh of thee the suspicion of how they must suffer from ill-will" (Greek Anthology, 251).

Lucian, who also wrote in Greek, satirizes the foolish collector, asking "How can you tell what books are old and highly valuable, and what are worthless and simply in wretched repair—unless you judge them by the extent to which they are eaten into and cut up, calling the book-worms into counsel to settle the question?" (The Ignorant Book Collector, I.)

Of the Latin poets, Horace, fearing for the fate of a book so eager to be sold, ruefully addresses it as he would a handsome slave, warning that, after being packed up and sent to the provinces, it finally will be used as a lesson book in some insignificant school on the outskirts of town. "You will be loved in Rome till your youth leave you; when you've been well thumbed by vulgar hands and begin to grow soiled, you will either in silence be food for vandal moths, or will run away to Utica or be sent in bonds to Ilerda" (Epistles, XX). Simply being clever was not sufficient, as Martial (who also wrote about the lives of books when they had left his hands) cautioned. "But this, trust me, is not enough to bring fame; how many fluent writers feed moths and bookworms." (Epigrams, VI.61). And Ovid, in bitter relegation to Pontus on the shore of the Black Sea, complained of "the constant gnawing of sorrow," comparing it to that of the bookworm "as the book when laid away is nibbled by the worm's teeth" (Ex Ponto, I.1.72)—anticipating Hooke's wonderfully alliterative "the teeth of Time."

The Ænigmata of Symphosius is a collection of one-hundred riddles in Latin probably written in the fourth or fifth century AD, but possibly earlier.

"A letter was my food, yet I know not what the letter is. In books I lived, yet I am no more studious on that account. I devoured the Muses, yet so far I have made no progress" (XVI).

Developed from this enigmata, there is a similar Anglo-Saxon riddle in the Exeter Book.

"A moth ate words. To me it seemed a remarkable fate, when I learned of the marvel, that the worm had swallowed the speech of a man, a thief in the night, a renowned saying and its place itself. Though he swallowed the word the thieving stranger was no whit the wiser" (XLII).

The answer, of course, is the bookworm (Latin tinea).

References: Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon (1665) by R. Hooke; Insect Enemies of Books (1937) by Harry B. Weiss and Ralph H. Carruthers (a reprint of the Bulletin of the New York Public Library, September-December, 1936); The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (2012) by Stephen Greenblatt; Ovid: Tristia, Ex Ponto (1924) translated by Arthur Leslie Wheeler (Loeb Classical Library); Horace: Satires, Epistles and Ars Poetica (1926) translated by H. Rushton Fairclough (Loeb Classical Library); The Greek Anthology (1917) translated by W. R. Paton (Loeb Classical Library); Lucian: The Ignorant Book Collector (1921) translated by A. M. Harmon (Loeb Classical Library); Martial: Epigrams (1919) translated by Walter C. A. Ker (Loeb Classical Library); Aristotle: The History of Animals (1910) translated by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson; Pliny the Elder: The Natural History (1855) translated by John Bostock and H. T. Riley; Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book (1963) translated by Paull F. Baum; Old English Riddles (1912) edited by A. J. Wyatt.

See also Enigmata.